Sequence Is True For The Lytic Cycle Of A Virus

News Leon

Mar 21, 2025 · 8 min read

Table of Contents

The Lytic Cycle: A Step-by-Step Sequence of Viral Destruction

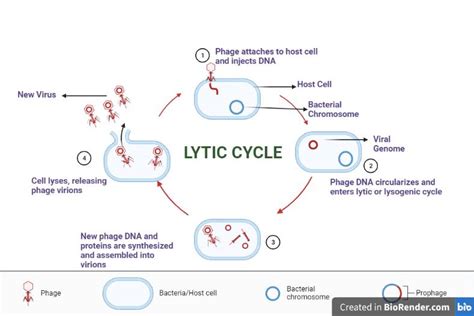

The lytic cycle is a crucial stage in the life cycle of many viruses, particularly bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria). This process, characterized by its destructive nature, culminates in the lysis (rupture) of the host cell, releasing newly assembled viral progeny to infect more cells. Understanding the precise sequence of events in the lytic cycle is vital for comprehending viral pathogenesis, developing antiviral therapies, and harnessing phages for therapeutic purposes (phage therapy). This article provides a detailed, step-by-step exploration of the lytic cycle, emphasizing the key events and the underlying mechanisms that drive this destructive process.

The Five Stages of the Lytic Cycle

The lytic cycle is typically described as having five distinct stages: attachment, penetration, biosynthesis, maturation, and release. Each stage involves specific viral and host cell components and interactions, contributing to the overall efficiency and propagation of the virus.

1. Attachment (Adsorption): The Initial Contact

The lytic cycle begins with attachment, also known as adsorption. This crucial first step involves the specific binding of the virus to a susceptible host cell. Viruses are incredibly specific; they possess surface proteins (e.g., spikes, fibers) that recognize and bind to complementary receptor molecules on the surface of the host cell. This interaction is akin to a "lock and key" mechanism, ensuring that the virus only infects cells with the appropriate receptors. The specificity of attachment determines the host range of the virus – which species and even cell types it can infect.

Specificity and the Host Range: The specificity of viral attachment is crucial for viral pathogenesis. A virus's inability to attach to its target cells renders it harmless. The evolution of viral surface proteins has led to remarkable adaptations that enable infection of specific host cells. This specificity also underlies the tissue tropism of many viruses, meaning they preferentially infect certain tissues or organs within the host organism. For example, the HIV virus targets specific cells of the immune system (CD4+ T cells).

Factors Affecting Attachment: Several factors influence the efficiency of attachment. These include the concentration of the virus and the number of available receptors on the host cell surface. Environmental conditions such as pH and temperature also play a role, as they can affect the conformation of viral attachment proteins and host cell receptors.

2. Penetration (Entry): Gaining Access to the Host Cell Interior

After successful attachment, the virus must penetrate the host cell and deliver its genetic material (DNA or RNA) into the cytoplasm. The penetration mechanism varies depending on the type of virus. Some viruses employ direct penetration, injecting their genome through the host cell membrane. Others use receptor-mediated endocytosis, a process where the host cell engulfs the entire virus within a vesicle. Once inside the cell, the viral capsid (protein coat) is degraded, releasing the viral genome.

Mechanisms of Penetration: The diversity of penetration mechanisms reflects the evolutionary adaptations of viruses to overcome the barriers presented by diverse host cells. For instance, enveloped viruses, those surrounded by a lipid membrane derived from the host cell, often fuse their envelope with the host cell membrane, releasing their nucleocapsid into the cytoplasm. Non-enveloped viruses typically rely on receptor-mediated endocytosis or direct penetration.

Uncoating: Following penetration, the viral capsid undergoes uncoating, a process that releases the viral genome. This often involves the action of host cell enzymes or viral-encoded proteins that degrade the capsid. Uncoating is essential for the next stage, biosynthesis.

3. Biosynthesis (Replication): Hijacking the Cellular Machinery

Biosynthesis is the stage where the virus takes control of the host cell’s machinery to replicate its genetic material and synthesize viral proteins. The viral genome directs the host cell's ribosomes to produce viral proteins, which are crucial for assembling new viral particles. Meanwhile, the viral genome is replicated numerous times, creating multiple copies to be packaged into new virions. This process effectively turns the host cell into a viral factory.

Viral Genome Replication Strategies: The replication strategy employed during biosynthesis depends on the type of viral genome. DNA viruses typically use the host cell's DNA polymerase to replicate their DNA. RNA viruses, however, require RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRps), which are often encoded by the viral genome itself, to replicate their RNA. The intricacies of viral genome replication are complex and reflect the evolutionary arms race between viruses and their hosts.

Viral Protein Synthesis: The synthesis of viral proteins involves transcription (DNA to RNA) and translation (RNA to protein). The viral genome directs the host cell’s transcription machinery to produce messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules that code for viral proteins. These mRNA molecules are then translated by host cell ribosomes into viral proteins.

4. Maturation (Assembly): Building New Virions

During maturation, or assembly, newly synthesized viral components—including viral genomes and proteins—are assembled into complete, infectious viral particles, known as virions. This process involves the precise interaction and self-assembly of various viral proteins and nucleic acids. This is often a highly orchestrated process, with specific chaperone proteins assisting in the proper folding and assembly of viral structures.

Self-Assembly: The remarkable ability of viruses to self-assemble is a testament to the elegant design encoded within their genomes. The interactions between viral proteins and nucleic acids are highly specific, ensuring the correct assembly of the virion. Despite its complexity, this self-assembly process is remarkably efficient and ensures the production of a large number of infectious viral particles.

Structural Complexity: The complexity of virion assembly varies widely among viruses. Some viruses have simple structures, while others have highly complex architectures, with intricate protein interactions and modifications.

5. Release (Lysis): Escape and Spread

The final stage, release, marks the end of the lytic cycle and the beginning of a new round of infection. In this stage, newly assembled virions are released from the host cell. The most common mechanism is lysis, where the host cell bursts, releasing hundreds or thousands of viral particles. This process is often mediated by viral-encoded enzymes, such as lysozyme in bacteriophages, that degrade the host cell wall or membrane.

Alternative Release Mechanisms: While lysis is the characteristic release mechanism of the lytic cycle, some viruses employ alternative strategies. Enveloped viruses, for example, can bud from the host cell membrane, acquiring a lipid envelope in the process. This budding process does not necessarily kill the host cell immediately, allowing for a more prolonged period of viral production.

Consequences of Lysis: The lysis of the host cell is a hallmark of the lytic cycle. The release of a large number of infectious virions allows for rapid spread and further infection of surrounding cells. This explains the rapid progression of lytic viral infections.

Variations and Exceptions in the Lytic Cycle

While the five stages described above represent the general sequence of the lytic cycle, there are variations and exceptions among different viruses. Some viruses may exhibit modifications to one or more of these stages, reflecting the diverse evolutionary strategies employed by these obligate intracellular parasites.

Variations in Attachment: The specific receptors used for attachment can vary greatly, influencing the tropism and host range of the virus. Some viruses may utilize multiple receptors for attachment, enhancing their infectivity.

Variations in Penetration: The mechanisms of penetration can differ among viruses, as discussed earlier. Some viruses may use alternative entry pathways, such as direct fusion with the host cell membrane or endocytosis via different pathways.

Variations in Biosynthesis: The specific mechanisms and timing of viral genome replication and protein synthesis can also vary. Some viruses may encode their own enzymes for replication, whereas others rely entirely on host cell enzymes.

Variations in Maturation and Release: The process of virion assembly can vary in complexity, depending on the virus’s structural features. The release mechanism can also vary, with some viruses employing budding instead of lysis.

The Lytic Cycle and its Implications

Understanding the precise sequence of events in the lytic cycle is critical for several reasons:

-

Developing antiviral therapies: Targeting specific steps in the lytic cycle can provide potential strategies for developing antiviral drugs. For instance, drugs can be designed to inhibit viral attachment, penetration, replication, or assembly.

-

Phage therapy: Bacteriophages that undergo the lytic cycle are increasingly being explored as a potential alternative to antibiotics in the treatment of bacterial infections. The ability of phages to specifically target and destroy bacteria makes them a promising therapeutic agent.

-

Understanding viral pathogenesis: A thorough understanding of the lytic cycle is essential for understanding how viruses cause disease. By elucidating the mechanisms by which viruses replicate and spread, we can develop strategies to prevent and treat viral infections.

-

Viral evolution: Studying the lytic cycle can provide insights into viral evolution and adaptation. The variations and modifications in different viruses highlight the dynamic interplay between viruses and their hosts.

Conclusion: A Devastatingly Precise Process

The lytic cycle is a remarkable and devastatingly precise process that underscores the remarkable adaptability and efficiency of viruses. Each step, from attachment to release, is carefully orchestrated, leading to the destruction of the host cell and the release of numerous viral progeny. Understanding the intricacies of this process is essential not only for combating viral infections but also for appreciating the remarkable evolutionary strategies of these obligate intracellular parasites. Continued research on the lytic cycle will undoubtedly lead to new discoveries and innovations in the fields of virology, antiviral therapy, and phage therapy, ultimately contributing to improved human health and disease management.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Percent Of 12 5 Is 39

Mar 28, 2025

-

In The Figure A Plastic Rod Having A Uniformly

Mar 28, 2025

-

Which Is Not True About The Genetic Code

Mar 28, 2025

-

In An Atom The Nucleus Contains

Mar 28, 2025

-

What Does Chr Do In Python

Mar 28, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Sequence Is True For The Lytic Cycle Of A Virus . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.