The Solubility Of A Solute Depends On

News Leon

Mar 19, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

The Solubility of a Solute Depends On: A Deep Dive into Dissolution

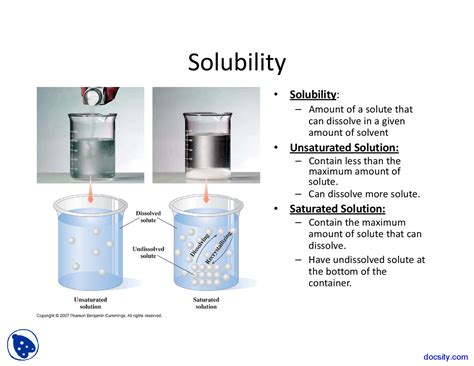

The solubility of a solute, the maximum amount of solute that can dissolve in a given amount of solvent at a specific temperature and pressure, is a fundamental concept in chemistry with far-reaching implications in various fields. Understanding the factors that influence solubility is crucial in numerous applications, from pharmaceutical drug delivery and environmental remediation to industrial processes and everyday life. This comprehensive exploration delves into the intricate details of solute solubility, examining the key factors that dictate how much of a substance will dissolve in a particular solvent.

1. The Nature of the Solute and Solvent: "Like Dissolves Like"

The most fundamental principle governing solubility is the adage, "like dissolves like." This implies that polar solvents tend to dissolve polar solutes, while nonpolar solvents dissolve nonpolar solutes. This principle stems from the nature of intermolecular forces.

1.1 Polarity and Intermolecular Forces

-

Polar Solvents: These solvents possess a significant difference in electronegativity between their constituent atoms, leading to a separation of charge and the formation of a dipole moment. Water (H₂O) is a prime example, with its highly polar O-H bonds. Other polar solvents include ethanol (CH₃CH₂OH), acetone (CH₃COCH₃), and methanol (CH₃OH). Polar solvents interact strongly with polar solutes through dipole-dipole interactions and hydrogen bonding.

-

Nonpolar Solvents: These solvents have a relatively uniform distribution of charge, resulting in little to no dipole moment. Examples include hexane (C₆H₁₄), benzene (C₆H₆), and carbon tetrachloride (CCl₄). Nonpolar solvents interact with nonpolar solutes primarily through weak London dispersion forces.

-

Polar Solutes: These solutes possess a dipole moment due to the unequal sharing of electrons in their bonds. Ionic compounds, like NaCl, are highly polar due to the complete transfer of electrons, forming charged ions. Many organic molecules with polar functional groups (like -OH, -COOH, -NH₂) are also considered polar solutes.

-

Nonpolar Solutes: These solutes have a balanced distribution of charge and primarily interact through weak London dispersion forces. Examples include hydrocarbons like fats and oils.

The strength of the interactions between solute and solvent molecules dictates the solubility. Strong solute-solvent interactions lead to higher solubility, while weak interactions result in low solubility. For instance, NaCl readily dissolves in water because the strong ion-dipole interactions between Na⁺ and Cl⁻ ions and water molecules overcome the strong ionic bonds in the crystal lattice. In contrast, NaCl is insoluble in hexane because the weak interactions between ions and hexane molecules are insufficient to overcome the strong ionic bonds.

1.2 Hydrogen Bonding

A special type of dipole-dipole interaction, hydrogen bonding, significantly influences solubility. Hydrogen bonding occurs when a hydrogen atom bonded to a highly electronegative atom (like oxygen, nitrogen, or fluorine) is attracted to another electronegative atom in a different molecule. This strong interaction is particularly important in the solubility of many organic compounds containing -OH, -NH, and -COOH groups in water. Molecules capable of forming hydrogen bonds with water readily dissolve in water.

2. Temperature: The Heat of Solution

Temperature plays a crucial role in determining solubility. The effect of temperature on solubility depends on the enthalpy of solution (ΔHsoln), the heat absorbed or released when a solute dissolves in a solvent.

2.1 Exothermic vs. Endothermic Dissolution

-

Exothermic Dissolution (ΔHsoln < 0): Heat is released when the solute dissolves. In these cases, solubility generally decreases with increasing temperature. This is because the system seeks to minimize the heat released, according to Le Chatelier's principle.

-

Endothermic Dissolution (ΔHsoln > 0): Heat is absorbed when the solute dissolves. In these cases, solubility generally increases with increasing temperature. The system absorbs heat to favor the dissolution process.

The majority of solid solutes exhibit increased solubility with increasing temperature because the process is endothermic. The energy input from heating helps overcome the intermolecular forces holding the solute together. However, the relationship isn't always straightforward and depends on the specific solute and solvent. For some gases, solubility decreases with increasing temperature, as the gas molecules gain kinetic energy and escape the solution.

3. Pressure: The Impact on Gas Solubility

Pressure significantly affects the solubility of gases, particularly in liquid solvents. This relationship is governed by Henry's Law, which states that the solubility of a gas in a liquid is directly proportional to the partial pressure of the gas above the liquid.

3.1 Henry's Law and its Implications

Henry's Law is expressed mathematically as:

C = kP

Where:

- C is the concentration of the dissolved gas

- k is Henry's law constant (specific to the gas and solvent)

- P is the partial pressure of the gas above the liquid

Therefore, increasing the pressure of a gas above a liquid increases its solubility. Conversely, decreasing the pressure decreases the solubility, leading to the release of dissolved gas (like opening a carbonated beverage). This is why scuba divers need to ascend slowly to avoid decompression sickness ("the bends"), where dissolved nitrogen gas bubbles form in their bloodstream due to rapid pressure decrease. The pressure effect on the solubility of solids and liquids is generally negligible.

4. Particle Size: Surface Area Matters

The particle size of a solid solute directly impacts its dissolution rate, although it doesn't necessarily affect the ultimate solubility (the maximum amount that can dissolve). Smaller particles have a larger surface area relative to their volume. A larger surface area allows for more frequent collisions between solute particles and solvent molecules, thus accelerating the dissolution process. This is why powdered sugar dissolves faster than a sugar cube—the powder offers a much greater surface area for interaction with water.

5. The Presence of Other Substances: Common Ion Effect and Complex Ion Formation

The solubility of a solute can be significantly altered by the presence of other substances in the solution.

5.1 The Common Ion Effect

The common ion effect reduces the solubility of a sparingly soluble salt when a common ion is added to the solution. For example, the solubility of AgCl (silver chloride) is reduced by adding NaCl (sodium chloride) to the solution because the increased concentration of chloride ions (Cl⁻) shifts the equilibrium of the dissolution reaction to the left, according to Le Chatelier's principle. This effect is particularly relevant in qualitative analysis and precipitation reactions.

5.2 Complex Ion Formation

Complex ion formation can significantly increase the solubility of a sparingly soluble salt. A complex ion is formed when a metal ion bonds to one or more ligands (molecules or ions). For instance, the solubility of AgCl increases drastically in the presence of ammonia (NH₃) because the silver ions (Ag⁺) form a complex ion with ammonia, [Ag(NH₃)₂]⁺. This complex ion formation removes Ag⁺ ions from solution, shifting the equilibrium of the dissolution reaction to the right and increasing the solubility of AgCl.

6. Other Factors Influencing Solubility

While the factors discussed above are the primary determinants of solubility, several other factors can play a minor, yet sometimes significant, role:

-

Solvent-Solvent Interactions: The interactions between solvent molecules themselves can influence the ability of the solvent to accommodate solute molecules. Strong solvent-solvent interactions might hinder solute dissolution.

-

Stirring/Agitation: Stirring or agitating the solution facilitates the dissolution process by constantly replenishing solvent molecules at the solute surface. However, stirring does not affect the ultimate solubility.

-

Impurities: The presence of impurities in the solvent or solute can affect solubility, although the effect is often complex and unpredictable.

Conclusion: A Holistic Perspective on Solubility

The solubility of a solute is a complex interplay of numerous factors, primarily the nature of the solute and solvent, temperature, pressure (for gases), particle size, and the presence of other substances. Understanding these factors is essential for various scientific and technological applications. From designing pharmaceuticals to predicting environmental impacts, a thorough grasp of solubility principles is crucial for accurate predictions and successful outcomes. By considering all these aspects holistically, one can develop a more complete and nuanced understanding of this fundamental chemical phenomenon. Further research and exploration into the subtle nuances of solubility will continue to refine our understanding and lead to new innovations across diverse fields.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Water V At 90 Degrees Celsius

Mar 19, 2025

-

How Fast Do Nerve Impulses Travel

Mar 19, 2025

-

What Set Of Reflections Would Carry Hexagon Abcdef Onto Itself

Mar 19, 2025

-

Is Aluminum Hydroxide Soluble In Water

Mar 19, 2025

-

Which Element Has Chemical Properties Most Similar To Sodium

Mar 19, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about The Solubility Of A Solute Depends On . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.