In The Figure Two Particles Each With Mass M

News Leon

Mar 24, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

In the Figure: Two Particles, Each with Mass m – A Deep Dive into Classical Mechanics

This article delves into the fascinating world of classical mechanics, specifically analyzing a system comprising two particles, each with mass 'm'. We'll explore various scenarios, examining the forces acting upon them, their resultant motion, and the underlying principles governing their interactions. This analysis will cover concepts such as momentum, kinetic energy, potential energy, and the application of Newton's laws of motion. We will also touch upon more advanced concepts as applicable, to build a robust understanding of the system.

Understanding the Fundamental Concepts

Before we dive into specific examples, let's refresh our understanding of some key concepts:

1. Newton's Laws of Motion:

- Newton's First Law (Inertia): A body at rest will remain at rest, and a body in motion will remain in motion with a constant velocity, unless acted upon by an external force.

- Newton's Second Law (F=ma): The acceleration of an object is directly proportional to the net force acting on it and inversely proportional to its mass. This is expressed mathematically as F = ma, where F is the net force, m is the mass, and a is the acceleration.

- Newton's Third Law (Action-Reaction): For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. This means that when one body exerts a force on another, the second body simultaneously exerts a force equal in magnitude and opposite in direction on the first body.

2. Momentum:

Momentum (p) is a measure of the mass in motion and is given by the formula: p = mv, where 'm' is the mass and 'v' is the velocity. The total momentum of a system remains constant in the absence of external forces (conservation of momentum).

3. Kinetic Energy:

Kinetic energy (KE) is the energy an object possesses due to its motion. It's calculated using the formula: KE = 1/2 mv², where 'm' is the mass and 'v' is the velocity.

4. Potential Energy:

Potential energy (PE) is the energy stored within an object due to its position or configuration. The type of potential energy depends on the forces acting on the object. Common examples include gravitational potential energy and elastic potential energy.

Scenario 1: Two Particles with No External Forces

Let's consider the simplest case: two particles, each with mass 'm', moving in a frictionless environment with no external forces acting upon them. According to Newton's First Law, each particle will maintain its initial velocity. The total momentum of the system will remain constant.

Analysis: Since there are no external forces, the total momentum before and after any interaction remains constant. If the particles collide elastically, kinetic energy will also be conserved. If the collision is inelastic, some kinetic energy will be lost, usually converted into heat or sound.

Mathematical Representation: The total momentum (P) of the system can be represented as: P = mv₁ + mv₂, where v₁ and v₂ are the velocities of the two particles. In the absence of external forces, dP/dt = 0.

Scenario 2: Two Particles Interacting via a Spring

Now, let's introduce an interaction between the two particles: a massless spring connecting them. Initially, the spring is either compressed or stretched.

Analysis: The spring exerts a force on each particle, obeying Newton's Third Law. The force is proportional to the displacement from the equilibrium position (Hooke's Law: F = -kx, where k is the spring constant and x is the displacement). The system will oscillate, exhibiting simple harmonic motion.

Mathematical Representation: Using Newton's Second Law for each particle, we can derive the equations of motion. The total energy of the system (kinetic energy + potential energy) will remain constant, assuming no energy loss due to friction. The potential energy stored in the spring is given by: PE = 1/2 kx².

Key Concepts Illustrated: This scenario beautifully illustrates the interplay between potential and kinetic energy, the conservation of energy in a closed system (ignoring energy losses), and the application of Newton's Second Law in a system with internal forces.

Scenario 3: Two Particles Under the Influence of Gravity

Let's place the two particles in a gravitational field. We'll assume the particles are significantly smaller than the distance between them and the source of gravity.

Analysis: Each particle experiences a gravitational force proportional to its mass and inversely proportional to the square of its distance from the gravitational source (Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation: F = Gm₁m₂/r² where G is the gravitational constant, m₁ and m₂ are the masses, and r is the distance between them). If the particles are initially at rest relative to each other, the gravitational force will cause them to accelerate towards each other.

Mathematical Representation: Newton's Second Law can be applied individually to each particle, taking into account the gravitational force acting on each. The gravitational potential energy will be converted into kinetic energy as the particles move closer.

Key Concepts Illustrated: This scenario showcases the application of Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation, the conversion between potential and kinetic energy, and the concept of gravitational potential energy.

Scenario 4: Two Particles with Collision – Elastic and Inelastic

Let’s analyze the collision between the two particles, differentiating between elastic and inelastic collisions.

Elastic Collision:

In an elastic collision, both momentum and kinetic energy are conserved. This implies that the particles bounce off each other without any loss of kinetic energy.

Analysis: Using the conservation of momentum and kinetic energy, we can determine the final velocities of the particles after the collision based on their initial velocities. The equations are:

- Conservation of Momentum: mv₁ᵢ + mv₂ᵢ = mv₁f + mv₂f (where i denotes initial velocity and f denotes final velocity)

- Conservation of Kinetic Energy: 1/2mv₁ᵢ² + 1/2mv₂ᵢ² = 1/2mv₁f² + 1/2mv₂f²

Solving these equations simultaneously allows us to calculate the final velocities.

Inelastic Collision:

In an inelastic collision, momentum is conserved, but kinetic energy is not. Some kinetic energy is lost, usually converted into other forms of energy such as heat, sound, or deformation.

Analysis: The conservation of momentum equation remains the same as in the elastic collision. However, the kinetic energy equation is no longer applicable. The loss of kinetic energy is often represented by a coefficient of restitution (e), which is the ratio of the relative velocity after the collision to the relative velocity before the collision. For a perfectly inelastic collision, e = 0, and the particles stick together after the collision.

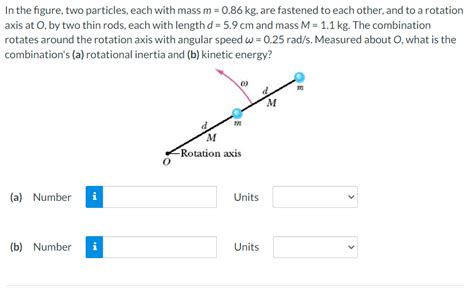

Scenario 5: Two Particles in a Rotating Frame

Let's place the two particles on a rotating platform. Now, we need to consider centripetal and centrifugal forces.

Analysis: In addition to any other forces, each particle experiences a centripetal force towards the center of rotation, keeping it in a circular path. In the rotating frame of reference, an observer will also observe a fictitious centrifugal force acting outwards, away from the center of rotation. These forces complicate the analysis, particularly if the particles interact with each other simultaneously.

Mathematical Representation: The equations of motion become more complex in a rotating frame, requiring the inclusion of Coriolis forces and centrifugal forces in addition to any other forces present.

Advanced Concepts and Further Exploration

This analysis only scratches the surface of the possibilities. More advanced concepts could be integrated, depending on the specific circumstances:

- Relativistic Effects: At very high velocities, relativistic effects become important and the classical mechanics equations need to be modified using Einstein's theory of special relativity.

- Electromagnetic Interactions: If the particles have electric charges, electromagnetic forces will also play a significant role, adding complexity to the analysis.

- Quantum Mechanics: At the atomic and subatomic level, classical mechanics breaks down, and quantum mechanics must be used to describe the behavior of the particles.

Conclusion

The seemingly simple system of two particles, each with mass 'm', opens up a vast array of possibilities for exploring fundamental concepts in classical mechanics. By varying the forces acting on the particles and their initial conditions, we can explore concepts like momentum, energy conservation, Newton's laws, and more advanced topics such as collisions, rotation and even glimpses into relativistic or quantum phenomena depending on the context. This analysis serves as a foundation for understanding more complex systems and highlights the power and elegance of classical mechanics in describing the physical world. Further investigation into these scenarios will provide a deeper understanding of the principles governing particle interactions and motion.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

The Fibrous Connective Tissue That Wraps Muscle Is Called

Mar 26, 2025

-

An Oscillator Consists Of A Block Attached To A Spring

Mar 26, 2025

-

Ecg Is A Graphic Recording Of

Mar 26, 2025

-

The Most Abundant Type Of Immunoglobulin Is

Mar 26, 2025

-

What Does The Slope Of A Distance Time Graph Represent

Mar 26, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about In The Figure Two Particles Each With Mass M . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.