Where In The Atom Are Electrons Located

News Leon

Mar 14, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

Where in the Atom Are Electrons Located? A Deep Dive into Atomic Structure

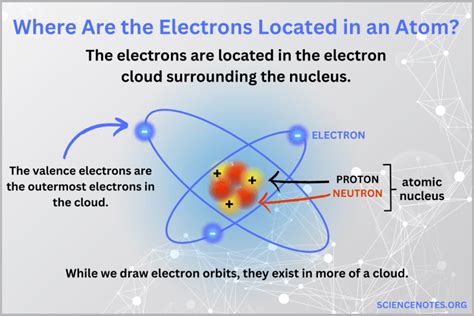

The question of where electrons are located within an atom is a cornerstone of atomic theory, and the answer isn't as simple as a pinpoint location. It's a journey into the quantum realm, requiring an understanding of probability, wave functions, and the limitations of classical physics. This article will delve into the fascinating world of atomic structure, exploring the historical development of our understanding of electron location, the limitations of classical models, and the modern quantum mechanical description.

The Early Models: Limitations of Classical Physics

Early attempts to describe the atom, such as the plum pudding model proposed by J.J. Thomson, pictured electrons embedded within a positively charged sphere. This model, however, failed to explain experimental observations, particularly the results of Rutherford's gold foil experiment.

Rutherford's Gold Foil Experiment and the Nuclear Model

Ernest Rutherford's groundbreaking experiment in 1911 revolutionized our understanding of atomic structure. By bombarding a thin gold foil with alpha particles, he observed that most particles passed through undeflected, while a few were scattered at large angles. This led him to propose the nuclear model, where a small, dense, positively charged nucleus resides at the center of the atom, with electrons orbiting it.

This model, while a significant improvement, still suffered from fundamental flaws. Classical electromagnetism predicted that orbiting electrons, being constantly accelerated, would radiate energy and spiral into the nucleus, causing the atom to collapse. This clearly contradicted the stability of atoms observed in nature.

The Bohr Model: A Quantum Leap

Niels Bohr's model in 1913 attempted to address the instability problem by incorporating concepts from quantum mechanics. Bohr proposed that electrons could only exist in specific, quantized energy levels or orbits around the nucleus. Electrons could jump between these energy levels by absorbing or emitting photons of specific energies, corresponding to the difference in energy between the levels.

Quantized Energy Levels and Electron Shells

The Bohr model introduced the concept of electron shells, representing discrete energy levels. Electrons in the lowest energy level (closest to the nucleus) are said to be in the ground state. Higher energy levels correspond to excited states. This model successfully explained the discrete spectral lines observed in the hydrogen atom's emission spectrum. Each line corresponds to a specific energy transition of an electron between two energy levels.

However, the Bohr model, while a crucial step forward, was still limited. It accurately predicted the hydrogen spectrum but failed to account for the spectra of more complex atoms with multiple electrons. It also couldn't explain the fine structure of spectral lines or the intensities of the lines.

The Quantum Mechanical Model: Probability and Orbitals

The shortcomings of the Bohr model highlighted the need for a more sophisticated approach. The development of quantum mechanics in the 1920s provided the necessary framework. This theory replaced the deterministic orbits of the Bohr model with a probabilistic description of electron location.

The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle

A cornerstone of quantum mechanics is the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, which states that it's impossible to simultaneously know both the position and momentum of an electron with perfect accuracy. The more precisely we know one, the less precisely we know the other. This inherent uncertainty means we can't talk about electrons following precise paths or orbits.

Wave-Particle Duality and the Schrödinger Equation

Quantum mechanics describes electrons as having both wave-like and particle-like properties. This wave-particle duality is captured by the Schrödinger equation, a fundamental equation of quantum mechanics that describes the evolution of the electron's wave function over time.

Electron Orbitals and Probability Density

The solution to the Schrödinger equation provides the electron's wave function, denoted by ψ (psi). The square of the wave function, |ψ|², gives the probability density of finding the electron at a particular location in space. This probability density is often represented visually as an orbital, a region of space where there is a high probability of finding the electron.

Orbitals are not fixed paths like planetary orbits; they are regions of space where an electron is likely to be found. Different orbitals have different shapes and energy levels, depending on the quantum numbers that describe the electron's state.

Quantum Numbers: Defining Electron States

The state of an electron in an atom is described by a set of four quantum numbers:

-

Principal quantum number (n): Determines the energy level and size of the orbital. It can take positive integer values (n = 1, 2, 3,...). Higher values of n correspond to higher energy levels and larger orbitals.

-

Azimuthal quantum number (l): Determines the shape of the orbital and its angular momentum. It can take integer values from 0 to n-1. l = 0 corresponds to an s orbital (spherical), l = 1 to a p orbital (dumbbell-shaped), l = 2 to a d orbital (more complex shapes), and so on.

-

Magnetic quantum number (ml): Determines the orientation of the orbital in space. It can take integer values from -l to +l, including 0. For example, a p orbital (l=1) has three possible orientations (ml = -1, 0, +1).

-

Spin quantum number (ms): Describes the intrinsic angular momentum of the electron, often referred to as its spin. It can take two values: +1/2 (spin up) or -1/2 (spin down).

Each electron in an atom is uniquely identified by its set of four quantum numbers, a consequence of the Pauli Exclusion Principle, which states that no two electrons in an atom can have the same set of four quantum numbers.

Electron Configuration and the Periodic Table

The arrangement of electrons in an atom, described by the quantum numbers, is called its electron configuration. The electron configuration determines the atom's chemical properties and its position in the periodic table. Elements in the same column (group) of the periodic table have similar electron configurations in their outermost shell (valence electrons), leading to similar chemical behavior.

Filling Orbitals: Aufbau Principle and Hund's Rule

Electrons fill orbitals according to the Aufbau principle, which states that electrons first fill the lowest energy levels available. Hund's rule states that electrons will singly occupy each orbital within a subshell before pairing up in the same orbital. This minimizes electron-electron repulsion and leads to greater stability.

Beyond Simple Atoms: Multi-electron Systems and Electron Correlation

For atoms with multiple electrons, the Schrödinger equation becomes significantly more complex to solve. The interaction between electrons (electron correlation) needs to be considered, which makes exact solutions practically impossible for all but the simplest systems. Approximation methods are used to predict electron configurations and properties of more complex atoms and molecules.

Computational Chemistry and Advanced Techniques

Modern computational chemistry techniques, such as density functional theory (DFT) and Hartree-Fock methods, are employed to approximate the solutions of the Schrödinger equation for complex systems. These techniques provide valuable insights into electron distributions and other properties of atoms and molecules.

Conclusion: Probabilistic Nature of Electron Location

In summary, the location of electrons in an atom is not a definite, classical position. Instead, it's described probabilistically by the quantum mechanical model. Electrons occupy orbitals, regions of space where the probability of finding them is high. These orbitals are characterized by quantum numbers, which determine their energy, shape, and orientation. The understanding of electron location is fundamental to comprehending the behavior of atoms, molecules, and materials, driving advancements in diverse fields like chemistry, physics, and materials science. The journey from the simplistic plum pudding model to the sophisticated quantum mechanical description highlights the remarkable progress in our understanding of the fundamental building blocks of matter. The ongoing research in this area continues to refine our understanding and unravel further complexities of the atomic world.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

How Many Lone Pairs Does Nitrogen Have

Mar 14, 2025

-

When Does The Nuclear Membrane Disappear

Mar 14, 2025

-

Which Definition Best Describes Polygenic Traits

Mar 14, 2025

-

What Is The Symbol Of Tin

Mar 14, 2025

-

How Many Valence Electrons Are In Zinc

Mar 14, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Where In The Atom Are Electrons Located . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.