What Controls What Enters And Leaves A Cell

News Leon

Mar 14, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

What Controls What Enters and Leaves a Cell? The Intricate World of Cell Membranes

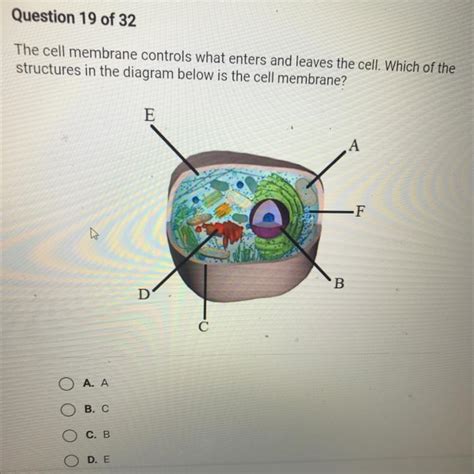

The seemingly simple question, "What controls what enters and leaves a cell?" unveils a complex and fascinating world of cellular biology. The answer lies in the cell membrane, a selectively permeable barrier that regulates the passage of substances into and out of the cell. This intricate structure, far from being a passive wall, plays a crucial role in maintaining cellular homeostasis, enabling communication, and facilitating various cellular processes. Understanding the mechanisms governing this selective permeability is fundamental to comprehending the functioning of life itself.

The Structure of the Cell Membrane: A Dynamic Barrier

The cell membrane, also known as the plasma membrane, is a fluid mosaic model composed primarily of a phospholipid bilayer. This bilayer consists of two layers of phospholipid molecules, each with a hydrophilic (water-loving) head and two hydrophobic (water-fearing) tails. The hydrophilic heads face outwards, interacting with the aqueous environments inside and outside the cell, while the hydrophobic tails cluster inwards, creating a barrier to water-soluble substances.

Key Components of the Cell Membrane:

- Phospholipids: The fundamental structural components, forming the bilayer. Their amphipathic nature is crucial for the membrane's selective permeability.

- Cholesterol: Embedded within the phospholipid bilayer, cholesterol modulates membrane fluidity. It prevents the membrane from becoming too rigid at low temperatures and too fluid at high temperatures, maintaining its structural integrity.

- Proteins: Integral and peripheral proteins are embedded within or associated with the membrane. These proteins perform diverse functions, including transport, enzymatic activity, cell signaling, and cell adhesion.

- Carbohydrates: Attached to lipids (glycolipids) or proteins (glycoproteins), carbohydrates play crucial roles in cell recognition, cell signaling, and immune responses.

This dynamic arrangement allows for the fluidity of the membrane, enabling its components to move laterally within the bilayer. This fluidity is essential for various cellular processes, including membrane fusion, cell division, and receptor-mediated endocytosis.

Mechanisms of Transport Across the Cell Membrane: Selective Permeability in Action

The cell membrane's selective permeability ensures that only certain substances can cross it, while others are excluded. This selectivity is achieved through various transport mechanisms, broadly classified into passive and active transport.

Passive Transport: No Energy Required

Passive transport mechanisms do not require energy expenditure by the cell. Substances move down their concentration gradient, from an area of high concentration to an area of low concentration. This movement continues until equilibrium is reached.

- Simple Diffusion: Small, nonpolar molecules like oxygen and carbon dioxide can diffuse directly across the lipid bilayer. Their hydrophobic nature allows them to readily pass through the hydrophobic core of the membrane.

- Facilitated Diffusion: Larger or polar molecules that cannot readily cross the lipid bilayer require the assistance of membrane proteins. These proteins act as channels or carriers, facilitating the movement of specific substances down their concentration gradient. Examples include glucose transporters and ion channels.

- Osmosis: The movement of water across a selectively permeable membrane from an area of high water concentration (low solute concentration) to an area of low water concentration (high solute concentration). Osmosis is crucial for maintaining cell turgor and preventing cell lysis or crenation.

Active Transport: Energy-Dependent Movement

Active transport mechanisms require energy, typically in the form of ATP, to move substances against their concentration gradient, from an area of low concentration to an area of high concentration. This process is essential for maintaining concentration gradients crucial for cellular function.

- Primary Active Transport: Directly utilizes ATP to move substances against their concentration gradient. A classic example is the sodium-potassium pump (Na+/K+ ATPase), which maintains the electrochemical gradient across the cell membrane, vital for nerve impulse transmission and muscle contraction.

- Secondary Active Transport: Utilizes the energy stored in an electrochemical gradient created by primary active transport. This gradient is then used to transport another substance against its concentration gradient. Cotransport (symport) involves the simultaneous movement of two substances in the same direction, while countertransport (antiport) involves the movement of two substances in opposite directions.

Vesicular Transport: Bulk Movement of Substances

Vesicular transport involves the movement of large molecules or bulk quantities of substances across the cell membrane using membrane-bound vesicles. This process is energy-dependent and plays a crucial role in endocytosis and exocytosis.

Endocytosis: Bringing Substances into the Cell

Endocytosis involves the engulfment of extracellular materials by the cell membrane, forming vesicles that transport the material into the cell. There are three main types of endocytosis:

- Phagocytosis: "Cell eating," the engulfment of large particles, such as bacteria or cellular debris.

- Pinocytosis: "Cell drinking," the uptake of fluids and dissolved substances.

- Receptor-mediated endocytosis: A highly specific process where substances bind to receptors on the cell surface, triggering the formation of a coated pit that invaginates to form a vesicle. This mechanism is crucial for the uptake of cholesterol and other specific molecules.

Exocytosis: Releasing Substances from the Cell

Exocytosis is the reverse process of endocytosis, involving the fusion of vesicles with the cell membrane, releasing their contents into the extracellular space. This process is essential for secretion of hormones, neurotransmitters, and other molecules.

Regulation of Cell Membrane Permeability: Maintaining Homeostasis

The cell's ability to regulate the permeability of its membrane is critical for maintaining homeostasis—the stable internal environment necessary for its survival. This regulation is achieved through various mechanisms, including:

- Control of protein expression: Cells can regulate the number and type of transport proteins in their membrane, affecting the permeability to specific substances.

- Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of transport proteins: Changes in the phosphorylation state of transport proteins can alter their activity and thereby affect membrane permeability.

- Changes in membrane fluidity: Factors that affect membrane fluidity, such as temperature and cholesterol content, can indirectly influence membrane permeability.

- Formation of specialized membrane domains: Certain regions of the cell membrane may have different protein compositions and permeability characteristics compared to other regions.

Cell Membrane Dysfunction and Disease

Disruptions in the structure or function of the cell membrane can have significant consequences for cellular health and can contribute to various diseases. These disruptions can result from genetic mutations, infections, or exposure to toxins. Examples include:

- Cystic fibrosis: Caused by mutations in the gene encoding the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein, affecting chloride ion transport across the cell membrane.

- Familial hypercholesterolemia: Caused by mutations in genes encoding LDL receptors, impairing the uptake of cholesterol from the blood.

- Various inherited metabolic disorders: Often caused by defects in membrane transport proteins, affecting the transport of specific molecules.

Conclusion: The Cell Membrane – A Master Regulator of Life

The cell membrane is not simply a boundary; it is a highly dynamic and sophisticated structure that plays a pivotal role in controlling what enters and leaves a cell. Its selective permeability, achieved through a combination of passive and active transport mechanisms, is essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis, enabling communication, and facilitating numerous cellular processes. Understanding the intricacies of the cell membrane and its associated transport mechanisms is paramount in advancing our knowledge of cell biology and addressing various human diseases. Further research in this area holds the key to developing novel therapeutic strategies targeting membrane-related diseases and enhancing our overall understanding of life itself. The cell membrane, a seemingly simple structure, reveals itself as a master regulator of life, a testament to the elegant complexity of biological systems.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Percent Of 90 Is 120

Mar 14, 2025

-

How Many Chambers Does The Heart Of An Amphibian Have

Mar 14, 2025

-

Is Boiling Water Chemical Or Physical Change

Mar 14, 2025

-

A Goal Of The Defense Plant Corporation Was

Mar 14, 2025

-

The Ends Of A Long Bone Are Called The

Mar 14, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about What Controls What Enters And Leaves A Cell . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.