The Body In The Figure Is Pivoted At O

News Leon

Mar 15, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

The Body in the Figure is Pivoted at O: A Comprehensive Exploration of Rotational Mechanics

Understanding rotational motion is crucial in various fields, from engineering and physics to robotics and biomechanics. A fundamental concept within this realm involves analyzing a rigid body pivoted at a point, often designated as 'O'. This article delves deep into the mechanics of such a system, exploring its key characteristics, governing equations, and practical applications. We'll examine forces, torques, moments of inertia, angular acceleration, and energy considerations within this framework.

Understanding the Pivot Point (O)

The pivot point, 'O', acts as the center of rotation for the rigid body. It's the point about which the body rotates, remaining stationary throughout the motion. This point is crucial because it defines the reference point for all calculations related to rotational motion. The nature of the pivot—whether frictionless or possessing some resistance—significantly influences the system's dynamics. A frictionless pivot allows for pure rotation without any energy loss due to friction, while a pivot with friction introduces resistive forces that must be accounted for.

Types of Pivots and Their Implications

Several types of pivots exist, each impacting the system's behavior differently:

-

Frictionless Pivot: An idealized scenario where no frictional forces oppose the rotation. This simplifies calculations significantly, allowing for the application of conservation of energy principles.

-

Pivot with Friction: A more realistic scenario where frictional forces at the pivot oppose the rotation. This introduces energy loss, making the system more complex to analyze. The frictional forces depend on the nature of the surfaces in contact and the normal force at the pivot.

-

Fixed Pivot: A pivot that is firmly fixed in place, unable to move or shift under load.

-

Flexible Pivot: A pivot that can flex or deform slightly under load, altering the system's behavior and requiring more complex modeling techniques.

Forces and Torques: The Driving Factors of Rotation

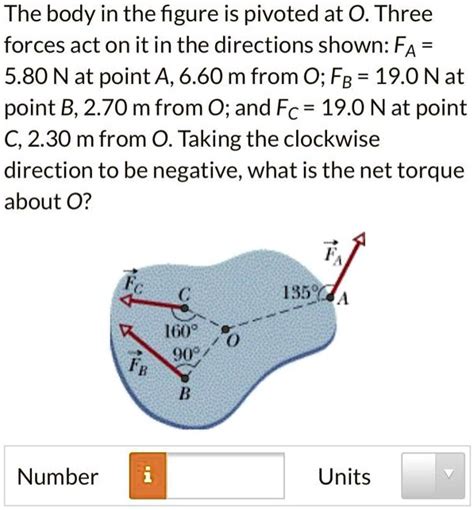

The rotation of a rigid body pivoted at O is governed by the net torque acting on it. Torque, often denoted by 'τ' (tau), is the rotational equivalent of force in linear motion. It's calculated as the cross product of the force vector and the position vector from the pivot point to the point of force application:

τ = r x F

Where:

- τ is the torque vector

- r is the position vector from the pivot (O) to the point of force application

- F is the force vector

The magnitude of the torque is given by:

|τ| = rFsinθ

Where θ is the angle between the force vector and the position vector. This equation highlights the importance of both the magnitude of the force and its perpendicular distance from the pivot point. A larger force or a greater distance from the pivot leads to a larger torque.

The Role of Multiple Forces

When multiple forces act on the body, the net torque is the vector sum of the individual torques:

τ_net = Σ τ_i

The direction of the net torque determines the direction of angular acceleration. A positive net torque causes counter-clockwise rotation (assuming a standard coordinate system), while a negative net torque causes clockwise rotation.

Moment of Inertia: Resistance to Rotational Acceleration

The moment of inertia (I), analogous to mass in linear motion, represents a body's resistance to changes in its rotational motion. It depends on the mass distribution of the body relative to the pivot point. For a point mass 'm' at a distance 'r' from the pivot, the moment of inertia is:

I = mr²

For more complex objects, the moment of inertia is calculated by integrating over the entire mass distribution:

I = ∫ r² dm

The moment of inertia is crucial because it connects the net torque to the angular acceleration (α) through Newton's second law for rotation:

τ_net = Iα

Calculating Moment of Inertia for Different Shapes

Calculating the moment of inertia can be challenging for irregularly shaped objects. However, for common shapes like disks, rods, and spheres, standard formulas exist. These formulas are readily available in physics and engineering handbooks and are essential for analyzing rotational motion accurately.

Angular Acceleration and Angular Velocity

Angular acceleration (α) represents the rate of change of angular velocity (ω). Angular velocity describes how quickly the body is rotating, expressed in radians per second. The relationship between angular acceleration, angular velocity, and time is analogous to the linear motion equations:

- ω_f = ω_i + αt (constant angular acceleration)

- θ = ω_i t + ½ αt² (constant angular acceleration)

- ω_f² = ω_i² + 2αθ (constant angular acceleration)

Where:

- ω_i is the initial angular velocity

- ω_f is the final angular velocity

- θ is the angular displacement

Energy Considerations in Rotational Motion

The energy of a rotating body includes both rotational kinetic energy and potential energy (if the body is subject to gravitational forces). Rotational kinetic energy (KE_rot) is given by:

KE_rot = ½ Iω²

The total mechanical energy of the system is the sum of rotational kinetic energy, translational kinetic energy (if the pivot point itself is moving), and potential energy. In a frictionless system, the total mechanical energy is conserved.

Conservation of Energy in Rotational Systems

The principle of conservation of energy is particularly useful for analyzing rotational motion. In the absence of friction or other non-conservative forces, the total mechanical energy remains constant throughout the motion. This principle provides a powerful tool for solving problems involving rotational motion, especially those involving changes in height or velocity.

Practical Applications and Examples

The concept of a rigid body pivoted at a point has widespread applications:

-

Mechanical Engineering: Analyzing gears, pulleys, and rotating shafts. Understanding torque, moment of inertia, and stress distributions is crucial for designing safe and efficient machinery.

-

Physics: Studying the motion of pendulums, gyroscopes, and rotating objects in general. The principles of rotational mechanics are fundamental to understanding many physical phenomena.

-

Robotics: Controlling the movement of robotic arms and manipulators. Precise control of torque and angular acceleration is necessary for accurate and efficient robot movements.

-

Biomechanics: Analyzing human movement, such as joint rotations and limb movements. Understanding the mechanics of human joints helps in rehabilitation, sports training, and prosthetic design.

-

Astronomy: Modeling the rotation of planets and stars. The principles of rotational mechanics are fundamental to understanding celestial mechanics.

Advanced Concepts and Further Exploration

This article provides a foundational understanding of a rigid body pivoted at a point. However, more advanced concepts exist, such as:

-

Non-uniform density: Analyzing objects with non-uniform mass distribution requires more sophisticated mathematical techniques for calculating the moment of inertia.

-

Coupled rotational motion: Systems involving multiple rotating bodies interacting with each other require analyzing the coupled equations of motion.

-

Rotating reference frames: Analyzing motion from a rotating frame of reference introduces Coriolis and centrifugal forces, complicating the equations of motion.

-

Dynamic equilibrium: Analyzing systems under the influence of multiple torques and forces, ensuring rotational equilibrium.

Conclusion

The study of a rigid body pivoted at a point is fundamental to understanding rotational mechanics. By understanding the concepts of torque, moment of inertia, angular acceleration, and energy conservation, engineers, physicists, and other professionals can accurately model and predict the behavior of rotating systems. The principles discussed here form the basis for more advanced analyses in various fields, highlighting the significance of this seemingly simple yet profoundly influential concept in the world of mechanics. The application of these principles spans numerous disciplines, underscoring their importance in practical engineering and scientific endeavors. Further exploration of the advanced concepts mentioned above will provide a more complete and nuanced understanding of the rich dynamics involved in rotational motion.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Concave Mirror And Convex Mirror Difference

Mar 15, 2025

-

Which Is Not A Cranial Bone Of The Skull

Mar 15, 2025

-

Mountain Range That Separates Europe And Asia

Mar 15, 2025

-

16 Out Of 40 As A Percentage

Mar 15, 2025

-

Which Of The Following Is A True Solution

Mar 15, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about The Body In The Figure Is Pivoted At O . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.