Pertaining To Destruction Of Worn-out Red Blood Cells

News Leon

Mar 23, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

The Demise of Red Blood Cells: A Deep Dive into Erythrocyte Destruction

Red blood cells, or erythrocytes, are the tireless workhorses of our circulatory system, diligently delivering oxygen throughout our bodies. Their lifespan, however, is finite. After approximately 120 days, these vital cells reach the end of their functional life and must be efficiently removed from circulation. This process, known as erythrocyte destruction or hemolysis, is a crucial component of maintaining red blood cell homeostasis and overall health. A malfunction in this intricate process can lead to various health problems, highlighting the importance of understanding its mechanisms.

Understanding the Lifespan of Red Blood Cells

The relatively short lifespan of red blood cells is largely due to their unique structure and function. These biconcave discs, lacking a nucleus and other organelles, are highly specialized for oxygen transport. Their flexibility allows them to navigate the narrow capillaries, delivering oxygen to even the most remote tissues. However, this specialized structure also renders them incapable of self-repair. As they age, they accumulate damage, including:

Accumulation of Oxidative Damage:

The constant exposure to reactive oxygen species (ROS) during oxygen transport leads to the oxidation of proteins and lipids within the red blood cell membrane. This oxidative stress weakens the membrane, making it susceptible to damage and fragmentation.

Membrane Protein Alterations:

Over time, the essential membrane proteins responsible for maintaining the cell's shape and flexibility undergo structural changes. This leads to decreased deformability, impacting their ability to traverse the capillaries.

Enzyme Degradation:

The enzymes crucial for maintaining red blood cell metabolism, such as those involved in energy production and antioxidant defense, gradually lose their activity with age. This further compromises the cell's functionality and viability.

These cumulative changes ultimately signal the end of the erythrocyte's life cycle, triggering its destruction and removal from circulation.

The Mechanisms of Red Blood Cell Destruction

The destruction of worn-out red blood cells occurs primarily through two major pathways:

1. Extravascular Hemolysis:

This is the predominant mechanism accounting for approximately 90% of erythrocyte destruction. It occurs primarily in the reticuloendothelial system (RES), a network of phagocytic cells located throughout the body, mainly in the spleen, liver, and bone marrow. These phagocytes, including macrophages and Kupffer cells, recognize and engulf senescent or damaged red blood cells.

The process involves several key steps:

- Recognition of aged erythrocytes: Aged red blood cells display specific markers on their surface, such as altered membrane proteins and oxidized lipids, which are recognized by receptors on the surface of macrophages.

- Engulfment and degradation: The macrophages engulf the entire red blood cell, sequestering it within a phagosome. Lysosomes then fuse with the phagosome, releasing enzymes that break down the hemoglobin into its constituent components: heme and globin.

- Recycling of components: The globin is further broken down into amino acids, which are reused for protein synthesis. The iron from heme is transported to the bone marrow bound to transferrin, where it's incorporated into new hemoglobin molecules. The porphyrin ring of heme is converted into bilirubin, a yellowish pigment that's transported to the liver, conjugated, and excreted in bile.

The spleen plays a particularly important role in extravascular hemolysis due to its unique microenvironment. The spleen's narrow splenic sinusoids filter out rigid and inflexible red blood cells, effectively eliminating aged and damaged erythrocytes.

2. Intravascular Hemolysis:

This less common pathway involves the destruction of red blood cells directly within the bloodstream. It's typically associated with severe hemolytic anemias, where the rate of red blood cell destruction exceeds the bone marrow's capacity to compensate.

Causes of intravascular hemolysis include:

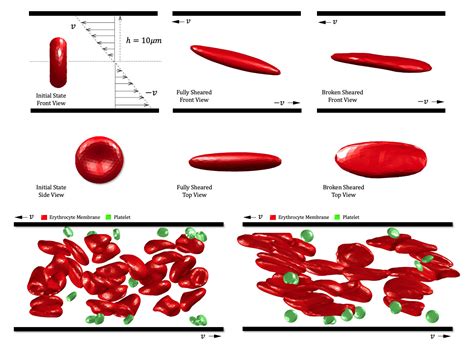

- Mechanical damage: This can occur due to artificial heart valves or other conditions causing shear stress on red blood cells.

- Complement activation: Certain antibodies or immune complexes can activate the complement system, leading to the formation of membrane attack complexes (MACs) that perforate the red blood cell membrane.

- Oxidative stress: Excessive oxidative stress can overwhelm the red blood cell's antioxidant defense mechanisms, leading to membrane damage and lysis.

During intravascular hemolysis, hemoglobin is released directly into the plasma. The free hemoglobin is then bound to haptoglobin, a plasma protein, which prevents its loss through the kidneys. However, if the rate of hemolysis exceeds the haptoglobin binding capacity, free hemoglobin can be filtered by the kidneys, potentially leading to hemoglobinuria (hemoglobin in the urine) and renal damage.

Clinical Significance of Erythrocyte Destruction

Disruptions in the normal processes of erythrocyte destruction can manifest in various clinical conditions:

Hemolytic Anemia:

This group of disorders is characterized by an increased rate of red blood cell destruction. It can be inherited (e.g., sickle cell anemia, thalassemia) or acquired (e.g., autoimmune hemolytic anemia, drug-induced hemolytic anemia). Symptoms often include anemia, jaundice (due to increased bilirubin levels), and splenomegaly (enlarged spleen).

Jaundice:

Excessive bilirubin accumulation, resulting from increased red blood cell destruction, can lead to jaundice, a yellowing of the skin and eyes. The severity of jaundice depends on the rate of bilirubin production and the liver's ability to process and excrete it.

Splenomegaly:

The spleen's increased workload in removing damaged red blood cells can lead to splenomegaly, an enlargement of the spleen. This can cause abdominal discomfort and an increased risk of splenic rupture.

Renal Dysfunction:

In cases of intravascular hemolysis, the release of free hemoglobin into the bloodstream can overwhelm the haptoglobin binding capacity, leading to hemoglobinuria and potentially causing kidney damage.

Diagnostic Approaches for Erythrocyte Destruction Disorders

Diagnosing disorders related to erythrocyte destruction often involves a combination of laboratory tests, including:

- Complete blood count (CBC): This provides information about the number and morphology of red blood cells, helping to identify anemia and other abnormalities.

- Peripheral blood smear: Microscopic examination of a blood smear can reveal characteristic changes in red blood cell shape and size, indicative of various hemolytic anemias.

- Reticulocyte count: This measures the number of immature red blood cells in the blood, reflecting the bone marrow's response to increased red blood cell destruction.

- Haptoglobin levels: Low haptoglobin levels suggest increased intravascular hemolysis.

- Bilirubin levels: Elevated bilirubin levels indicate increased red blood cell breakdown.

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels: Elevated LDH levels suggest cell damage, including red blood cell destruction.

- Coombs test (direct antiglobulin test): This test detects antibodies bound to red blood cells, helpful in diagnosing autoimmune hemolytic anemias.

Therapeutic Interventions

Treatment for disorders related to erythrocyte destruction depends on the underlying cause. Options may include:

- Medications: Corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, or other medications may be used to suppress the immune system in autoimmune hemolytic anemia.

- Splenectomy: Surgical removal of the spleen may be necessary in cases of severe hemolytic anemia where the spleen is actively contributing to red blood cell destruction.

- Blood transfusions: Blood transfusions may be required to manage anemia and maintain adequate oxygen-carrying capacity.

- Gene therapy: Gene therapy is an emerging field with potential to treat inherited hemolytic anemias by correcting the underlying genetic defect.

Conclusion

The destruction of worn-out red blood cells is a vital physiological process crucial for maintaining red blood cell homeostasis and overall health. This finely tuned mechanism involves complex interactions between various cells and organs. Understanding the intricate pathways involved in erythrocyte destruction is essential for diagnosing and managing various hemolytic disorders. Further research into the underlying mechanisms and therapeutic targets promises advancements in the treatment of these debilitating conditions. The multifaceted nature of this process emphasizes the intricate balance our bodies maintain, and the crucial role played by the seemingly simple red blood cell in maintaining our overall well-being. Future research will undoubtedly continue to unveil deeper insights into this crucial biological process, leading to improved diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies for the benefit of patients worldwide.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Both Sugarcane And Corn Are Examples Of

Mar 25, 2025

-

How Many Corners Has A Cuboid

Mar 25, 2025

-

3 X 4 X 5 X

Mar 25, 2025

-

Prevents Backflow Into The Right Atrium

Mar 25, 2025

-

What Information Does The Electronic Configuration Of An Atom Provide

Mar 25, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Pertaining To Destruction Of Worn-out Red Blood Cells . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.