Lysosomes Are Membrane Bound Vesicles That Arise From The

News Leon

Mar 25, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Lysosomes: Membrane-Bound Vesicles Arising from the Golgi Apparatus and Endoplasmic Reticulum

Lysosomes are fascinating organelles, vital for the health and survival of eukaryotic cells. These membrane-bound vesicles, often described as the cell's recycling centers or demolition crews, play a crucial role in various cellular processes. Understanding their origin, structure, function, and the implications of lysosomal dysfunction is key to grasping cellular biology. This article delves deep into the multifaceted world of lysosomes, exploring their formation, mechanisms of action, and the significant consequences of their malfunction.

The Genesis of Lysosomes: A Journey from the Golgi and ER

The origin of lysosomes is a complex process involving coordinated action between the Golgi apparatus and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). While the prevailing view points to the Golgi as the primary site of lysosome biogenesis, recent research highlights a more nuanced picture, suggesting contributions from both organelles.

The Golgi Apparatus: The Main Lysosome Factory

The Golgi apparatus, a central organelle in the secretory pathway, acts as the primary manufacturing and processing hub for many lysosomal enzymes. These enzymes, crucial for degrading various macromolecules, are synthesized in the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER). After synthesis, these newly formed enzymes are transported to the cis-Golgi network (CGN), the entry point of the Golgi stack.

Within the Golgi, these proteins undergo extensive post-translational modifications, including glycosylation. This modification is essential for targeting and proper functioning of lysosomal enzymes. The specific glycosylation pattern, particularly the addition of mannose-6-phosphate (M6P) tags, serves as a crucial signal for sorting these enzymes to the lysosomes.

Proteins lacking M6P tags are typically secreted from the cell. However, specialized proteins, including M6P receptors, within the trans-Golgi network (TGN), recognize and bind to M6P-tagged lysosomal enzymes. This recognition mechanism ensures that these essential enzymes are correctly packaged into vesicles destined for lysosomes.

The Endoplasmic Reticulum’s Contribution

While the Golgi is the central player in lysosome biogenesis, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), particularly the rough ER, plays a vital role in the initial synthesis of lysosomal enzymes. The RER's ribosomes translate the mRNA encoding these enzymes into nascent polypeptide chains. These chains then undergo folding and modification within the ER lumen.

The ER also contributes to the production of lysosomal membrane proteins, essential components of the lysosomal membrane that help maintain its structural integrity and regulate the trafficking of molecules in and out of the lysosome. These membrane proteins, like lysosomal enzymes, are glycosylated and subsequently targeted to the Golgi for further processing and sorting.

Lysosomal Structure: A Compartmentalized Environment

Lysosomes are characterized by their unique structural features that facilitate their function as intracellular degradation centers.

The Lysosomal Membrane: A Protective Barrier

The lysosomal membrane is a highly specialized lipid bilayer, crucial for maintaining the acidic environment inside the lysosome. This membrane is enriched in specific lipids and proteins, which are resistant to the destructive power of the hydrolytic enzymes contained within.

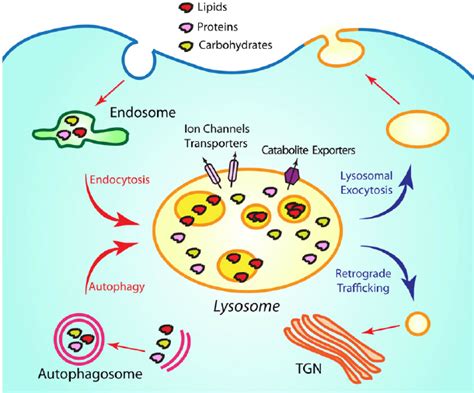

The membrane’s protein composition includes proton pumps (V-ATPases), responsible for maintaining the acidic pH (around 4.5–5.0) within the lysosome. This acidic pH is critical for the optimal activity of many lysosomal enzymes, which are typically acid hydrolases. The membrane also contains transporters that facilitate the movement of breakdown products out of the lysosomes. Specific channels and pumps regulate the transport of ions and smaller molecules across this barrier.

The Lysosomal Lumen: A Hydrolytic Haven

The lysosomal lumen, the interior space of the lysosome, contains a diverse array of hydrolytic enzymes. These enzymes are capable of degrading various biological macromolecules, including:

- Proteases: Break down proteins.

- Nucleases: Break down nucleic acids (DNA and RNA).

- Glycosidases: Break down carbohydrates.

- Lipases: Break down lipids.

- Phosphatases: Break down phosphate esters.

- Sulfatases: Break down sulfate esters.

These enzymes work synergistically to efficiently dismantle a wide range of cellular waste products and unwanted materials.

Lysosomal Function: Degradation, Recycling, and Beyond

Lysosomes are far more than just cellular waste disposal units; they are dynamic organelles participating in a wide range of crucial cellular processes.

Autophagy: Cellular Self-Renewal

Autophagy, a process of self-digestion, is a critical function mediated by lysosomes. During autophagy, damaged organelles, misfolded proteins, and other cellular debris are encapsulated within double-membrane vesicles called autophagosomes. These autophagosomes then fuse with lysosomes, delivering their cargo to the lysosomal hydrolases for degradation. The resulting breakdown products are recycled, providing the cell with valuable building blocks for new components. This process is essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis and preventing the accumulation of harmful cellular waste. It's a vital mechanism for cellular survival and renewal, especially under stress conditions like nutrient deprivation.

Phagocytosis: Engulfing and Eliminating

Phagocytosis, a form of endocytosis, involves the engulfment and digestion of large particles, such as bacteria and cellular debris, by specialized cells like macrophages and neutrophils. These particles are internalized into phagosomes, which then fuse with lysosomes, forming phagolysosomes. Within these structures, the lysosomal enzymes break down the engulfed material. This process is a key component of the immune system's defense against pathogens.

Endocytosis: Receptor-Mediated Uptake

Endocytosis, a broader process involving the internalization of extracellular material, also involves lysosomes. Receptor-mediated endocytosis is a specialized type of endocytosis where specific receptors on the cell surface bind to target molecules. These receptor-ligand complexes are internalized into vesicles, which subsequently fuse with early endosomes and then mature into late endosomes. These late endosomes then fuse with lysosomes, leading to the degradation of the internalized material. This pathway is essential for the uptake of essential nutrients, hormones, and other molecules.

Other Functions: Beyond the Basics

Lysosomes are involved in many other cellular functions, including:

- Bone resorption: Lysosomes in osteoclasts contribute to bone remodeling.

- Programmed cell death (apoptosis): Lysosomes can contribute to apoptosis by releasing their hydrolytic enzymes into the cytoplasm.

- Immune regulation: Lysosomes play a role in antigen presentation and immune response modulation.

Lysosomal Storage Diseases: Consequences of Dysfunction

Dysfunction of lysosomes, often due to genetic defects affecting lysosomal enzymes or transporters, leads to a group of conditions known as lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs). In these diseases, the inability to properly degrade specific substrates leads to their accumulation within lysosomes. This accumulation can cause cellular damage and dysfunction, resulting in a wide range of clinical manifestations depending on the specific enzyme deficiency.

Examples of LSDs include:

- Gaucher disease: Deficiency of glucocerebrosidase, leading to the accumulation of glucocerebroside.

- Tay-Sachs disease: Deficiency of hexosaminidase A, leading to the accumulation of ganglioside GM2.

- Pompe disease: Deficiency of acid α-glucosidase, leading to the accumulation of glycogen.

- Hurler syndrome: Deficiency of α-L-iduronidase, leading to the accumulation of glycosaminoglycans.

The severity and symptoms of LSDs vary widely depending on the specific enzyme affected and the extent of the deficiency. These diseases often result in progressive organ damage and neurological dysfunction. Research into therapeutic strategies for LSDs continues to develop, with ongoing efforts focusing on enzyme replacement therapy, substrate reduction therapy, and gene therapy.

Conclusion: Lysosomes – Essential for Cellular Life

Lysosomes are far more than just cellular "garbage disposals". These remarkable organelles are central players in a wide range of essential cellular processes, from maintaining cellular homeostasis to combating infections. Their multifaceted functions highlight their importance for cell survival and overall health. Understanding the biogenesis, structure, function, and pathology of lysosomes provides invaluable insight into fundamental cellular processes and sheds light on the pathogenesis of many devastating diseases. Continued research into lysosomal biology will undoubtedly unlock further knowledge about the intricate workings of the cell and pave the way for novel therapeutic interventions. The exploration of lysosomes remains a vibrant field, holding promising avenues for understanding disease and developing novel treatments.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

How Many Valence Electrons Does Alkali Metals Have

Mar 26, 2025

-

What Is The Conjugate Base Of H2po4

Mar 26, 2025

-

The Standard Unit Of Mass Is

Mar 26, 2025

-

What Is The Oxidation Number Of Cr In K2cr2o7

Mar 26, 2025

-

Which Of The Following Has Kinetic Energy

Mar 26, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Lysosomes Are Membrane Bound Vesicles That Arise From The . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.