In The Figure A Frictionless Roller Coaster Car Of Mass

News Leon

Mar 24, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

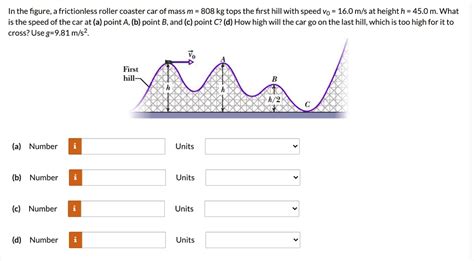

In the Figure, a Frictionless Roller Coaster Car of Mass: A Deep Dive into Energy Conservation and Mechanics

The classic physics problem of a frictionless roller coaster car traversing a track presents a fascinating opportunity to explore fundamental principles of energy conservation and mechanics. While idealized (frictionless systems rarely exist in the real world), this scenario provides a clear and accessible way to understand crucial concepts like potential energy, kinetic energy, and the interplay between them. This article will delve into a detailed analysis of this problem, exploring various scenarios and extensions to build a comprehensive understanding.

Understanding the Fundamentals: Potential and Kinetic Energy

Before we tackle the specifics of the roller coaster car, let's revisit the core concepts:

Potential Energy (PE):

Potential energy is the energy stored within an object due to its position or configuration. In the context of our roller coaster, the car possesses gravitational potential energy (GPE) due to its height above a reference point (usually ground level). The formula for GPE is:

GPE = mgh

where:

- m is the mass of the object (the roller coaster car)

- g is the acceleration due to gravity (approximately 9.8 m/s² on Earth)

- h is the height of the object above the reference point.

Kinetic Energy (KE):

Kinetic energy is the energy an object possesses due to its motion. The faster the object moves, the greater its kinetic energy. The formula for KE is:

KE = ½mv²

where:

- m is the mass of the object

- v is the velocity of the object.

The Principle of Conservation of Mechanical Energy

In a frictionless system, the total mechanical energy (the sum of potential and kinetic energy) remains constant. This means that as the roller coaster car moves along the track, energy is constantly converted between potential and kinetic energy, but the total amount remains unchanged. Mathematically, this is expressed as:

Total Mechanical Energy (E) = KE + GPE = constant

This principle forms the bedrock of our analysis of the roller coaster car's motion.

Analyzing the Roller Coaster's Journey: Different Track Scenarios

Let's consider several scenarios involving different track configurations:

Scenario 1: Simple Hill

Imagine a roller coaster car starting from rest at a height h₁ on a single hill. As it descends, its potential energy is converted into kinetic energy. At the bottom of the hill (height = 0), all the potential energy has been transformed into kinetic energy. We can use the conservation of energy principle to find its velocity at the bottom:

Initial energy (at height h₁): E₁ = mgh₁ (all potential energy)

Energy at the bottom (height = 0): E₂ = ½mv² (all kinetic energy)

Since E₁ = E₂, we have:

mgh₁ = ½mv²

Solving for v:

**v = √(2gh₁) **

This equation shows that the velocity at the bottom depends only on the initial height and gravity, not the mass of the car. This is a key insight from the conservation of energy.

Scenario 2: Multiple Hills

Now, let's add complexity by introducing multiple hills. As the car ascends a hill, its kinetic energy is converted back into potential energy. At the peak of each hill, the car will have a velocity determined by the energy conservation principle applied to that point on the track. The total energy remains constant throughout the journey, and we can track the conversion between kinetic and potential energy at every point.

Let's consider a second hill with height h₂. The car reaches its peak with a maximum height. At this point, kinetic energy is minimum and potential energy is maximum. At the peak of the second hill, the energy equation becomes:

mgh₁ = mgh₂ + ½mv²

The velocity at the peak of the second hill, v, will be less than the velocity at the bottom of the first hill, as some energy has been used to increase the height.

Scenario 3: Loops

Introducing loops adds another dimension to the problem. For the car to successfully navigate a loop, it needs sufficient kinetic energy at the bottom of the loop to overcome the gravitational pull at the top. At the top of the loop, the car needs a minimum velocity to stay on the track and not fall off. Let's analyze this scenario.

Minimum velocity at the top of a loop:

At the top of the loop of radius r, the only force acting downward is gravity (m*g). This should provide the centripetal force (mv²/r) required to stay on the circular path.

mg = mv²/r

v = √(gr)

This is the minimum velocity required at the top of the loop. The initial height needed to achieve this velocity can be determined using the principle of conservation of energy. The equation is complex and involves the loop's radius and initial height of the coaster.

Scenario 4: Incorporating Springs

We can further expand this by adding a spring at the bottom of a hill. As the car impacts the spring, kinetic energy is converted into elastic potential energy stored in the spring. The spring's compression allows for energy storage and release, further demonstrating the flexibility of the energy conservation principle.

Beyond the Idealization: Introducing Friction

The frictionless model provides a simplified framework. In reality, friction significantly affects the motion of a roller coaster car. Friction dissipates mechanical energy as heat, reducing the car's overall energy and consequently its maximum height and speed. The inclusion of friction necessitates a modification of our energy conservation equation to account for energy loss. A term representing the work done by friction needs to be added, resulting in:

E₁ - Work done by friction = E₂

Modeling friction accurately is more complex, often requiring knowledge of the specific friction coefficients between the car and track.

Conclusion: The Power of Energy Conservation

Analyzing the motion of a frictionless roller coaster car provides a valuable tool for understanding energy conservation. Although idealized, this model effectively highlights the transformation of energy between potential and kinetic forms. By exploring various scenarios, from simple hills to loops and springs, we can develop a strong grasp of this fundamental principle in physics. Extending the model to include friction provides a more realistic portrayal, demonstrating the limitations of ideal models and introducing additional factors to consider in real-world applications. This comprehensive approach reinforces the concepts of energy conservation and mechanics, laying a strong foundation for further exploration in more complex physics problems.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Is The Opposite Of Hyperbole

Mar 26, 2025

-

Major And Minor Grooves In Dna

Mar 26, 2025

-

Tendons And Ligaments Are Examples Of

Mar 26, 2025

-

A Homogeneous Mixture Of Two Or More Substances

Mar 26, 2025

-

Reaction Of Ethanol And Acetic Acid

Mar 26, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about In The Figure A Frictionless Roller Coaster Car Of Mass . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.