Each Hemoglobin Molecule Can Transport A Maximum Of Oxygen Molecules

News Leon

Mar 16, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

Each Hemoglobin Molecule Can Transport a Maximum of Four Oxygen Molecules: A Deep Dive into Hemoglobin's Oxygen-Carrying Capacity

Hemoglobin, a remarkable metalloprotein found in red blood cells, plays a pivotal role in oxygen transport throughout the body. Understanding its structure and function is crucial to grasping the intricacies of respiration and overall human physiology. This article delves into the specifics of hemoglobin's oxygen-carrying capacity, exploring the molecular mechanisms that allow each hemoglobin molecule to bind a maximum of four oxygen molecules. We will also touch upon the factors influencing oxygen binding and the clinical implications of hemoglobin dysfunction.

The Structure of Hemoglobin: A Foundation for Understanding Oxygen Binding

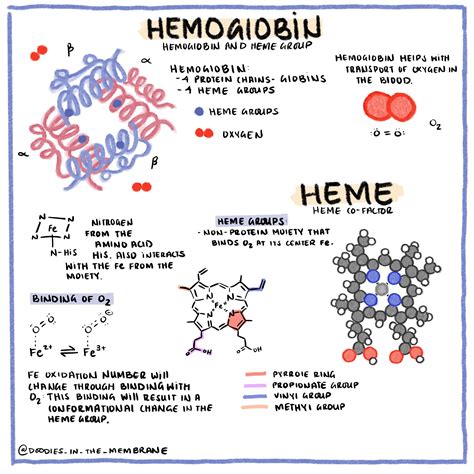

Hemoglobin's ability to bind four oxygen molecules is intrinsically linked to its quaternary structure. Each hemoglobin molecule is a tetramer, meaning it's composed of four individual protein subunits. In adult humans, this tetramer consists of two alpha (α) subunits and two beta (β) subunits, often represented as α₂β₂. Each subunit, in turn, comprises a polypeptide chain tightly associated with a heme group.

The Heme Group: The Oxygen-Binding Site

The heme group is the key player in oxygen binding. This prosthetic group, nestled within a hydrophobic pocket of each subunit, consists of a porphyrin ring complexed with a ferrous ion (Fe²⁺). It is the ferrous ion that directly binds to an oxygen molecule. The precise chemical interaction involves the formation of a coordinate covalent bond between the oxygen molecule and the iron ion. This bond is reversible, allowing for oxygen to be both picked up in the lungs and released in the tissues.

Cooperative Binding: The Power of Allosteric Regulation

The magic of hemoglobin doesn't lie solely in the individual oxygen-binding capacity of each heme group; it's the cooperative binding that truly amplifies its efficiency. The binding of the first oxygen molecule to one of the subunits induces a conformational change in the entire hemoglobin molecule. This change increases the affinity of the remaining subunits for oxygen, facilitating the rapid binding of the subsequent three oxygen molecules. This phenomenon, known as cooperative binding, is a prime example of allosteric regulation, where the binding of a molecule at one site influences the binding of another molecule at a different site.

Factors Affecting Hemoglobin's Oxygen-Binding Affinity

Several factors influence the affinity of hemoglobin for oxygen, affecting the efficiency of oxygen transport. These factors play crucial roles in regulating the delivery of oxygen to the tissues based on metabolic needs:

Partial Pressure of Oxygen (pO₂): The Driving Force

The partial pressure of oxygen (pO₂) in the environment directly influences oxygen binding. In the lungs, where pO₂ is high, hemoglobin readily binds oxygen. Conversely, in the tissues, where pO₂ is low due to cellular respiration, oxygen is released from hemoglobin. This gradient ensures efficient oxygen uptake and delivery.

pH: The Bohr Effect

Changes in pH significantly impact hemoglobin's oxygen-binding affinity. A decrease in pH (increased acidity), as seen in actively metabolizing tissues producing lactic acid and carbon dioxide, reduces hemoglobin's affinity for oxygen, promoting oxygen release. This is known as the Bohr effect. Conversely, a higher pH increases affinity.

Temperature: A Modulator of Affinity

Temperature also plays a role. Increased temperature, often associated with increased metabolic activity, decreases hemoglobin's affinity for oxygen, facilitating oxygen delivery to tissues requiring it.

2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG): A Key Regulator

2,3-BPG is a molecule found within red blood cells that binds to hemoglobin, decreasing its affinity for oxygen. Levels of 2,3-BPG are regulated, increasing during conditions of low oxygen availability (hypoxia) to enhance oxygen release to the tissues.

Clinical Implications of Hemoglobin Dysfunction

Dysfunctions in hemoglobin's structure or function can have significant clinical consequences. Several conditions illustrate the importance of proper hemoglobin function:

Anemia: Insufficient Oxygen-Carrying Capacity

Anemia is characterized by a reduced ability of the blood to carry oxygen, often due to decreased hemoglobin levels or abnormal hemoglobin structure. Various types of anemia exist, each with different underlying causes and clinical manifestations.

Sickle Cell Anemia: A Shape-Shifting Hemoglobin

Sickle cell anemia is a genetic disorder caused by a mutation in the β-globin gene, resulting in the production of abnormal hemoglobin S (HbS). HbS polymerizes under low oxygen conditions, causing red blood cells to deform into a sickle shape. These sickled cells obstruct blood flow, leading to pain crises, organ damage, and other severe complications.

Thalassemia: Imbalance in Globin Chain Synthesis

Thalassemia encompasses a group of inherited disorders characterized by reduced or absent synthesis of one or more globin chains. This imbalance leads to the formation of unstable hemoglobin molecules and a decrease in red blood cell production.

Beyond the Basics: Advanced Concepts in Hemoglobin Function

The discussion above provides a foundational understanding of hemoglobin's oxygen-carrying capacity. However, numerous complexities exist at a more advanced level:

Myoglobin: A Single-Subunit Oxygen Binder

Myoglobin, another heme-containing protein found primarily in muscle tissue, functions as an oxygen storage molecule. Unlike hemoglobin, myoglobin is a monomer (single subunit) with a significantly higher oxygen affinity than hemoglobin. This allows myoglobin to effectively store oxygen within muscle cells for use during periods of increased metabolic demand.

Hemoglobin Allosteric Model: A Refined Understanding

Various allosteric models aim to explain the cooperative binding of oxygen to hemoglobin. The concerted model postulates that all subunits transition synchronously between tense (T) and relaxed (R) states, while the sequential model suggests a more gradual transition. These models help illustrate the nuanced nature of allosteric regulation within the hemoglobin tetramer.

Fetal Hemoglobin: Enhanced Oxygen Affinity

Fetal hemoglobin (HbF), the primary oxygen-carrying molecule in the fetus, exhibits a higher oxygen affinity than adult hemoglobin (HbA). This allows the fetus to effectively extract oxygen from the maternal blood across the placental barrier.

Conclusion: The Vital Role of Hemoglobin in Oxygen Transport

The ability of each hemoglobin molecule to transport a maximum of four oxygen molecules is a testament to the exquisite design of this essential protein. Its cooperative binding, responsiveness to various factors, and sophisticated allosteric regulation enable efficient oxygen delivery throughout the body. Understanding the intricacies of hemoglobin function is crucial for comprehending the physiology of respiration and the pathogenesis of various hematological disorders. Further research continues to unravel the complexities of hemoglobin, providing valuable insights into its role in health and disease. The ongoing advancements in this field offer hope for improved diagnostics and treatments for hemoglobin-related conditions, ultimately enhancing human health and well-being.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Is Cl An Acid Or Base

Mar 17, 2025

-

A Charge Of Uniform Linear Density

Mar 17, 2025

-

Which Of The Following Is Polynomial

Mar 17, 2025

-

Is Boiling Water A Physical Change

Mar 17, 2025

-

Is A Webcam An Input Or Output Device

Mar 17, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Each Hemoglobin Molecule Can Transport A Maximum Of Oxygen Molecules . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.