An Electron Is Shot Into One End Of A Solenoid

News Leon

Mar 20, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

An Electron Shot into a Solenoid: Exploring the Physics of Magnetic Fields and Particle Motion

The seemingly simple scenario of an electron shot into a solenoid opens a fascinating window into the intricate world of electromagnetism and classical mechanics. This seemingly simple experiment reveals profound principles governing the interaction between charged particles and magnetic fields, principles with far-reaching implications in fields like particle accelerators, plasma physics, and even medical imaging. Let's delve into the physics behind this classic problem, exploring the forces at play, the resulting electron trajectory, and the nuances that arise under different conditions.

Understanding the Solenoid and its Magnetic Field

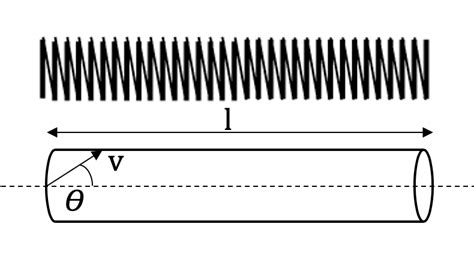

A solenoid is essentially a coil of wire, often tightly wound, that generates a magnetic field when an electric current passes through it. The magnetic field lines within the solenoid are remarkably uniform and parallel to the solenoid's axis, forming a near-perfect cylindrical magnetic field. This uniformity is crucial for understanding the electron's behavior inside. Outside the solenoid, the field lines are more complex, spreading out and resembling those of a bar magnet.

Key characteristics of the solenoid's magnetic field:

- Strength: The strength (magnitude) of the magnetic field inside the solenoid is directly proportional to the number of turns per unit length (n) and the current (I) flowing through the wire. This relationship is encapsulated in the equation: B = μ₀ * n * I, where μ₀ is the permeability of free space.

- Direction: The direction of the magnetic field is determined by the right-hand rule. If you curl the fingers of your right hand in the direction of the current flow, your thumb points in the direction of the magnetic field inside the solenoid.

- Uniformity: The magnetic field inside a long solenoid is remarkably uniform, especially near its center. This makes it an ideal environment for studying the motion of charged particles.

The Lorentz Force: Governing the Electron's Motion

When the electron enters the solenoid's uniform magnetic field, it experiences a force known as the Lorentz force. This force is fundamental to the interaction between charged particles and magnetic fields. The magnitude and direction of the Lorentz force are given by:

F = q * (v x B)

Where:

- F is the Lorentz force vector.

- q is the charge of the particle (in this case, the negative charge of the electron).

- v is the velocity vector of the electron.

- B is the magnetic field vector.

- x represents the cross product, indicating that the force is perpendicular to both the velocity and the magnetic field.

This perpendicularity is crucial. It means the Lorentz force does no work on the electron; it doesn't change the electron's speed, only its direction. This leads to the characteristic circular or helical motion we observe.

Trajectory of the Electron: Circular or Helical Motion?

The trajectory of the electron depends on the initial conditions: the direction of its velocity relative to the magnetic field.

Case 1: Electron's velocity perpendicular to the magnetic field

If the electron's initial velocity is perpendicular to the magnetic field lines (i.e., the electron enters the solenoid parallel to its axis), the Lorentz force continuously acts perpendicular to its velocity, forcing it into a circular path. The radius of this circular path (r) is determined by the balance between the centripetal force (mv²/r) and the Lorentz force:

mv²/r = qvB

Solving for the radius, we get:

r = mv / (qB)

This shows the radius is directly proportional to the electron's momentum (mv) and inversely proportional to the magnetic field strength (B) and the electron's charge (q).

Case 2: Electron's velocity at an angle to the magnetic field

If the electron's initial velocity has a component parallel to the magnetic field, in addition to the perpendicular component, the motion becomes helical. The parallel component of the velocity remains unaffected by the magnetic field, resulting in a uniform motion along the solenoid's axis. Simultaneously, the perpendicular component of the velocity causes the electron to execute circular motion around the magnetic field lines, creating a helical trajectory.

Factors Influencing the Electron's Path: A Deeper Dive

Several factors can influence the electron's path within the solenoid beyond the initial velocity and magnetic field strength:

- Electron's Energy: A higher energy electron (higher velocity) will have a larger radius of curvature in its circular or helical path.

- Magnetic Field Strength: A stronger magnetic field will cause a smaller radius of curvature, resulting in tighter spirals or circles.

- Solenoid Length: The length of the solenoid determines how long the electron interacts with the uniform magnetic field. A longer solenoid allows for more complete circular or helical turns.

- Electric Fields: The presence of electric fields (either externally applied or internal to the solenoid, if non-ideal) will significantly alter the electron’s trajectory, adding another layer of complexity to the analysis. The electron will experience a combination of electric and magnetic forces, leading to more complex and potentially non-periodic motion.

Applications and Implications

The principles governing the motion of an electron in a solenoid have profound implications across diverse scientific and technological domains:

- Particle Accelerators: Solenoids are crucial components in particle accelerators, employing their magnetic fields to guide and focus beams of charged particles to high energies. The precise control of the magnetic field allows for precise manipulation of particle trajectories.

- Plasma Confinement: In fusion research, solenoids are used to confine and shape plasmas, exploiting magnetic fields to contain extremely high-temperature charged particles. Understanding electron motion in these fields is essential for optimizing plasma confinement.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): The powerful, precisely controlled magnetic fields of solenoids form the heart of MRI machines. These fields interact with atomic nuclei in the body, allowing for the generation of detailed images.

- Electron Microscopes: Electron microscopes leverage magnetic lenses (essentially solenoids) to focus electron beams, enabling extremely high-resolution imaging of tiny structures.

Beyond Classical Mechanics: Quantum Effects

While the classical description above provides a robust understanding of electron motion in a solenoid under most conditions, at extremely small scales or in high-precision experiments, quantum mechanical effects must be considered. These effects include:

- Quantization of Energy Levels: In a strong magnetic field, the electron's energy levels become quantized, meaning they can only take on discrete values. This is known as Landau quantization, and it fundamentally alters the electron's behavior.

- Quantum Tunneling: Under certain circumstances, the electron might exhibit quantum tunneling, "passing through" potential barriers that would be insurmountable classically.

Conclusion

The seemingly simple scenario of an electron shot into a solenoid unfolds into a rich exploration of electromagnetic interactions and particle dynamics. The Lorentz force, the resulting circular or helical motion, and the influence of various factors all contribute to a fascinating interplay of forces. This seemingly basic experiment serves as a foundation for understanding numerous advanced concepts and applications in physics and technology, showcasing the enduring power of fundamental principles in revealing the complexities of the natural world. The study continues to evolve, with ongoing research exploring increasingly nuanced aspects of this interaction, extending our understanding of the fundamental forces governing the universe. From the macroscopic scale of particle accelerators to the microscopic realm of quantum mechanics, the solenoid continues to be a crucial tool in advancing our knowledge of physics.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Is The Function Of The Stigma In A Flower

Mar 21, 2025

-

When A Tuning Fork Vibrates Over An Open Pipe

Mar 21, 2025

-

Is Supports Combustion A Physical Property

Mar 21, 2025

-

Give The Constituents Of Baking Powder

Mar 21, 2025

-

Which Of The Following Types Of Muscles Is Voluntary Muscle

Mar 21, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about An Electron Is Shot Into One End Of A Solenoid . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.