A Proton Moves Through A Uniform Magnetic Field Given By

News Leon

Mar 23, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

The Dance of a Proton: Exploring Motion in a Uniform Magnetic Field

The behavior of a charged particle within a magnetic field is a fundamental concept in physics, with applications spanning diverse fields from particle accelerators to medical imaging. This article delves into the fascinating dynamics of a proton moving through a uniform magnetic field, exploring the underlying principles, mathematical descriptions, and practical implications. We'll examine the forces at play, the resulting trajectory, and variations depending on initial conditions.

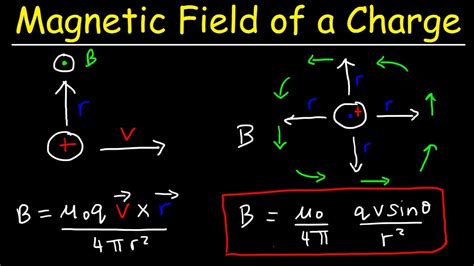

Understanding the Lorentz Force

The cornerstone of understanding a proton's motion in a magnetic field is the Lorentz force. This force acts on a charged particle moving in an electromagnetic field and is given by:

F = q(E + v x B)

Where:

- F represents the Lorentz force (in Newtons).

- q is the charge of the particle (for a proton, q = +1.602 x 10⁻¹⁹ Coulombs).

- E is the electric field vector (in Volts/meter).

- v is the velocity vector of the particle (in meters/second).

- B is the magnetic field vector (in Teslas).

- x denotes the cross product.

In a scenario with only a uniform magnetic field (E = 0), the equation simplifies to:

F = q(v x B)

This equation reveals a crucial aspect: the magnetic force is always perpendicular to both the velocity of the particle and the magnetic field. This perpendicularity has profound implications for the resulting motion.

Circular Motion in a Uniform Magnetic Field

Let's consider the simplest case: a proton enters a uniform magnetic field with its velocity perpendicular to the field lines. Because the magnetic force is always perpendicular to the velocity, it acts as a centripetal force, continuously changing the direction of the proton's velocity without altering its speed. This results in circular motion.

The centripetal force is given by:

F<sub>c</sub> = mv²/r

Where:

- m is the mass of the proton (approximately 1.673 x 10⁻²⁷ kg).

- v is the speed of the proton.

- r is the radius of the circular path.

Equating the Lorentz force and the centripetal force, we get:

qvB = mv²/r

Solving for the radius, we find:

r = mv/(qB)

This equation shows that the radius of the circular path is directly proportional to the proton's momentum (mv) and inversely proportional to the charge and the magnetic field strength. A higher momentum results in a larger radius, while a stronger magnetic field leads to a smaller radius.

The Cyclotron Frequency

As the proton moves in a circular path, it completes one revolution in a specific time period. The frequency of this revolution is known as the cyclotron frequency, denoted by ω (omega). It can be derived from the relationship between the velocity, radius, and period (T):

v = 2πr/T

Substituting the expression for the radius (r = mv/(qB)) and solving for ω (ω = 2π/T):

ω = qB/m

This equation demonstrates that the cyclotron frequency depends only on the charge-to-mass ratio (q/m) of the proton and the magnetic field strength. It's independent of the proton's speed or the radius of its orbit. This remarkable property is fundamental to the operation of cyclotrons, which accelerate charged particles using a time-varying electric field synchronized with the cyclotron frequency.

Helical Motion: The Case of an Oblique Angle

The circular motion discussed above is a special case where the proton's velocity is perfectly perpendicular to the magnetic field. When the initial velocity vector has a component parallel to the field, the motion becomes more complex – helical motion.

The parallel component of the velocity remains unchanged because the magnetic force is always perpendicular to it. This component results in a uniform motion along the magnetic field lines. Simultaneously, the perpendicular component of the velocity leads to the circular motion described earlier. The combination of these two motions creates a helical path, like a spring.

The pitch of the helix (the distance the proton travels along the magnetic field line in one revolution) is given by:

Pitch = v<sub>||</sub>T = 2πv<sub>||</sub>/(ω) = 2πmv<sub>||</sub>/(qB)

where v<sub>||</sub> is the component of the velocity parallel to the magnetic field.

Applications and Significance

The principles governing a proton's motion in a magnetic field have wide-ranging applications:

-

Particle Accelerators: Cyclotrons and synchrotrons utilize magnetic fields to bend and accelerate charged particles to high energies, used in research and medical applications.

-

Mass Spectrometry: Magnetic fields are crucial in mass spectrometers, which separate ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio. The radius of the circular path is directly related to this ratio, allowing for precise identification of molecules.

-

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI utilizes strong magnetic fields to align the magnetic moments of atomic nuclei (like protons in water molecules). The signals emitted by these nuclei when subjected to radio waves provide detailed images of the body's internal structures.

-

Fusion Research: Magnetic confinement fusion devices, such as tokamaks, employ powerful magnetic fields to contain and control the extremely hot plasma needed for nuclear fusion. The dynamics of charged particles within these fields are crucial for achieving sustained fusion reactions.

-

Space Physics: Charged particles from the sun (solar wind) interact with the Earth's magnetic field, creating phenomena like the aurora borealis. Understanding the motion of these particles in the magnetic field is crucial for studying space weather and its effects on our planet.

Advanced Considerations: Non-Uniform Magnetic Fields

The discussions above focus on uniform magnetic fields. In reality, magnetic fields are often non-uniform, leading to much more complex trajectories. These trajectories can involve drifts and other intricate motions. The analysis of these scenarios necessitates more advanced mathematical techniques, often involving numerical simulations.

For example, a gradient in the magnetic field strength (a change in B over space) can cause a gradient drift, where the particle drifts perpendicular to both the magnetic field gradient and the direction of the field. Similarly, a curvature in the magnetic field lines can result in curvature drift. These drifts are important in understanding plasma confinement in fusion devices and the motion of charged particles in the Earth's magnetosphere.

Conclusion

The motion of a proton in a uniform magnetic field is a fundamental and elegantly simple illustration of the interaction between charged particles and magnetic fields. Understanding the Lorentz force, the resulting circular or helical motion, and the cyclotron frequency provides a foundation for exploring the diverse applications of magnetic fields in science and technology. While uniform fields offer a clear starting point, the complexity increases significantly with non-uniform fields, highlighting the rich and multifaceted nature of charged particle dynamics in magnetic environments. The study of this fundamental interaction continues to drive advancements in various scientific fields and technological applications.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

A Gas Expands From I To F In The Figure

Mar 24, 2025

-

Place The Textile Industry Inventions In Chronological Order

Mar 24, 2025

-

Letter To The Editor Example Format

Mar 24, 2025

-

The Area Of Greatest Visual Acuity Is The

Mar 24, 2025

-

What Is The Electron Configuration Of Arsenic

Mar 24, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about A Proton Moves Through A Uniform Magnetic Field Given By . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.