A Flywheel With A Diameter Of 1.20m Is Rotating

News Leon

Mar 14, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

A Flywheel with a Diameter of 1.20m is Rotating: Exploring Rotational Motion and its Applications

A flywheel, a simple yet powerful device, is essentially a rotating mass designed to store rotational energy. Imagine a heavy wheel spinning rapidly; that's the basic principle. This article delves into the physics behind a flywheel with a diameter of 1.20m that's rotating, examining its properties, the forces at play, and its myriad applications in various fields. We'll explore concepts such as angular velocity, moment of inertia, kinetic energy, and the practical implications of these properties.

Understanding Rotational Motion

Before diving into the specifics of our 1.20m diameter flywheel, let's establish a foundational understanding of rotational motion. Unlike linear motion, which involves movement in a straight line, rotational motion describes the movement of an object around an axis. Key concepts include:

Angular Velocity (ω)

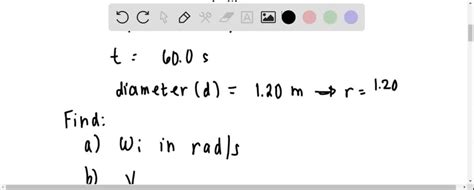

Angular velocity measures how fast an object rotates, expressed in radians per second (rad/s) or revolutions per minute (RPM). It's analogous to linear velocity (v) in linear motion. A higher angular velocity indicates a faster rotation. For our 1.20m flywheel, the angular velocity will directly influence its energy storage capacity and overall performance.

Angular Acceleration (α)

Angular acceleration represents the rate of change of angular velocity. If the flywheel's rotation speed increases, it's experiencing positive angular acceleration; if it slows down, it's experiencing negative angular acceleration (deceleration). This is crucial for understanding how the flywheel responds to external forces and torques.

Moment of Inertia (I)

Moment of inertia is the rotational equivalent of mass in linear motion. It measures an object's resistance to changes in its rotational motion. A higher moment of inertia means it's harder to start, stop, or change the flywheel's rotation speed. For our 1.20m flywheel, its moment of inertia depends heavily on its mass distribution and the material it's made of. A flywheel with a larger mass and mass concentrated further from the axis of rotation will have a significantly higher moment of inertia.

Calculating Moment of Inertia: The formula for the moment of inertia of a solid cylinder (a reasonable approximation for a flywheel) is: I = 1/2 * M * R², where M is the mass and R is the radius. Given the diameter (1.20m), the radius is 0.60m. Without knowing the mass (M), we can't calculate the exact value, but this formula highlights the relationship between mass, radius, and moment of inertia.

Torque (τ)

Torque is the rotational equivalent of force in linear motion. It's the twisting force that causes a change in rotational motion. Applying torque to our 1.20m flywheel can increase its angular velocity (positive torque) or decrease it (negative torque). The relationship between torque, moment of inertia, and angular acceleration is described by the equation: τ = I * α.

Rotational Kinetic Energy (KE<sub>rot</sub>)

Just like an object in linear motion possesses kinetic energy (KE = 1/2 * m * v²), a rotating object possesses rotational kinetic energy. The formula for rotational kinetic energy is: KE<sub>rot</sub> = 1/2 * I * ω². This equation showcases how the rotational kinetic energy directly relates to the moment of inertia and angular velocity. A higher angular velocity and a larger moment of inertia both contribute to a greater amount of stored rotational kinetic energy. This is the energy that a flywheel stores and releases.

Analyzing the 1.20m Diameter Flywheel

Now, let's focus specifically on the 1.20m diameter flywheel. Several factors significantly impact its behavior:

Material Selection

The material of the flywheel is crucial. Materials with high tensile strength and density are preferred to maximize energy storage for a given size and weight. Steel, carbon fiber composites, and even advanced materials like alloys are frequently used, each offering a unique trade-off between strength, weight, and cost. The choice of material directly affects the flywheel's moment of inertia and its ability to withstand the stresses of high-speed rotation.

Mass Distribution

The mass distribution within the flywheel influences its moment of inertia. A flywheel with mass concentrated at its outer rim will have a greater moment of inertia compared to one with the mass distributed more uniformly. This is because the outer mass contributes more to the rotational inertia, making it more resistant to changes in rotational speed. This design choice is crucial for maximizing energy storage.

Rotational Speed and Energy Storage

The rotational speed (ω) directly affects the flywheel's energy storage capability. As the angular velocity increases, the rotational kinetic energy increases quadratically (KE<sub>rot</sub> = 1/2 * I * ω²). However, higher speeds also introduce significant stress on the flywheel material, necessitating careful design and material selection to prevent catastrophic failure.

Applications of Flywheels

The 1.20m diameter flywheel, or flywheels of similar size, find applications in a diverse range of fields:

Energy Storage

Flywheels are increasingly used for energy storage in various applications, from hybrid vehicles to grid-scale energy storage systems. They can store energy efficiently and release it quickly, making them suitable for applications requiring rapid power delivery. The high energy density of a larger flywheel like our example makes it particularly attractive for this purpose.

Power smoothing

In machinery and power generation, flywheels help smooth out fluctuations in power output. They act as a buffer, absorbing excess energy during periods of high demand and releasing it when demand drops, ensuring smoother operation and reduced wear and tear on components. The rotational inertia helps maintain a consistent rotational speed, even in the face of fluctuating loads.

Kinetic Energy Recovery Systems (KERS)

Flywheels are integrated into Kinetic Energy Recovery Systems in racing cars and other vehicles. During braking, the kinetic energy of the vehicle is converted into rotational energy stored in the flywheel, which can then be used to boost acceleration. The larger diameter contributes to higher energy storage and power output.

Robotics and Automation

Flywheels can provide power for robotic actuators and automated systems, enabling quick and powerful movements. Their compact size and high power-to-weight ratio make them ideal for applications where space and weight are constraints.

Transportation

The applications of flywheels in transportation extend beyond racing cars. They are being explored as potential energy storage solutions for electric vehicles, public transport systems and even aircraft, offering a potential alternative to batteries in certain applications.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite their numerous advantages, flywheels also face certain challenges:

Energy Loss Due to Friction

Friction within the flywheel's bearings and the surrounding air causes energy loss. Minimizing friction through the use of advanced bearing technologies and housing designs is crucial to maintaining efficiency. Vacuum environments can minimize air resistance and improve energy retention.

Material Limitations

The tensile strength and fatigue resistance of flywheel materials limit the maximum rotational speed and energy storage capacity. The development of new materials and manufacturing techniques could significantly enhance their performance.

Cost

The manufacturing cost of flywheels can be relatively high, particularly for large-diameter, high-performance units. This is a barrier to broader adoption in certain applications. However, ongoing research and development are likely to drive down costs in the long term.

Conclusion

A 1.20m diameter flywheel rotating represents a fascinating example of the principles of rotational motion and its practical applications. Understanding concepts like angular velocity, moment of inertia, and rotational kinetic energy is crucial to optimizing the design and application of flywheels for various purposes. While challenges remain, advancements in materials science and engineering continue to unlock the potential of flywheels, making them increasingly relevant in diverse fields ranging from energy storage to transportation and robotics. The future of flywheel technology promises even more efficient and powerful applications, further solidifying its place as a vital component in various technological advancements.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

9 Is What Percent Of 72

Mar 15, 2025

-

How Many Valence Electrons Are In H

Mar 15, 2025

-

A Regular Quadrilateral Has What Type Of Symmetry

Mar 15, 2025

-

What Is The Conjugate Acid Of Oh

Mar 15, 2025

-

Which Of The Following Is Not A Renewable Resource

Mar 15, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about A Flywheel With A Diameter Of 1.20m Is Rotating . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.