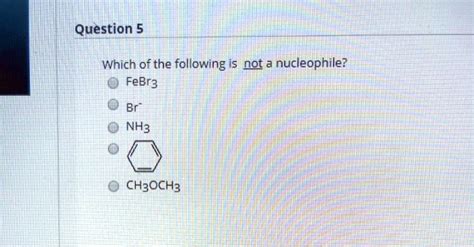

Which Of The Following Is Not A Nucleophile

News Leon

Mar 15, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

Which of the Following is NOT a Nucleophile? Understanding Nucleophilic Behavior

Nucleophiles, a cornerstone concept in organic chemistry, are electron-rich species that donate electrons to electron-deficient species, called electrophiles. This electron donation forms a new covalent bond, a fundamental reaction type in countless chemical processes. Understanding nucleophilicity is crucial for predicting reaction pathways and designing effective synthetic strategies. But what exactly makes a molecule a nucleophile, and more importantly, what doesn't? This article delves deep into the characteristics of nucleophiles, exploring the factors that influence their reactivity and highlighting examples of species that defy the typical nucleophilic profile.

Defining Nucleophilicity: More Than Just a Lone Pair

While many associate nucleophilicity solely with the presence of a lone pair of electrons, the reality is more nuanced. A molecule's ability to act as a nucleophile depends on several factors:

1. The Nature of the Nucleophile:

-

Charge: Negatively charged species are generally stronger nucleophiles than neutral molecules. The extra electron density increases their electron-donating ability. For example, hydroxide ion (OH⁻) is a much stronger nucleophile than water (H₂O).

-

Electronegativity: Less electronegative atoms are better nucleophiles. Atoms with lower electronegativity hold their electrons less tightly, making them more readily available for donation. For example, sulfur is a better nucleophile than oxygen because it is less electronegative. This explains why thiols (RSH) are generally more reactive than alcohols (ROH).

-

Steric Hindrance: Bulky groups around the nucleophilic atom can hinder its approach to the electrophile, reducing its nucleophilicity. A sterically hindered nucleophile might struggle to reach the electrophilic center, leading to slower reaction rates. Consider tert-butoxide compared to methoxide; the bulky tert-butyl groups significantly impede the approach of tert-butoxide to the electrophile.

2. The Solvent's Influence:

The solvent plays a critical role in modulating nucleophilicity. Protic solvents (those with an O-H or N-H bond) can solvate nucleophiles through hydrogen bonding, reducing their reactivity. This effect is particularly pronounced for negatively charged nucleophiles. Aprotic solvents (lacking O-H or N-H bonds), on the other hand, do not significantly hinder nucleophilic attack. Therefore, a strong nucleophile in a protic solvent might behave differently in an aprotic one.

3. The Leaving Group's Role:

While the focus is on the nucleophile, the leaving group (the atom or group displaced by the nucleophile) also significantly impacts the reaction. A good leaving group is one that stabilizes the negative charge acquired after leaving. This stability makes the departure of the leaving group easier, facilitating the nucleophilic attack. Halogens (F, Cl, Br, I) are generally good leaving groups, with iodide being the best due to its large size and polarizability.

Identifying Non-Nucleophiles: When Electron Donation Fails

Not all molecules with lone pairs are potent nucleophiles. Several factors can diminish or completely eliminate a molecule's nucleophilic character:

1. Strong Electron Withdrawing Groups (EWGs):

The presence of strong electron-withdrawing groups near the nucleophilic center significantly reduces electron density. These groups pull electron density away from the nucleophilic atom, making it less likely to donate electrons. For instance, trifluoroacetate ion (CF₃COO⁻) is a poor nucleophile despite carrying a negative charge. The electron-withdrawing trifluoromethyl group (CF₃) drastically reduces the electron density on the carboxylate oxygen, hindering its ability to act as a nucleophile.

2. Highly Stable Conjugate Bases:

Certain anions are exceptionally stable and resistant to nucleophilic attack. Their stability arises from resonance, aromaticity, or other stabilizing factors. This stability makes them reluctant to donate their electrons, effectively diminishing their nucleophilicity. For instance, carboxylate anions (RCOO⁻) are relatively weak nucleophiles due to resonance stabilization. The negative charge is delocalized over two oxygen atoms, making electron donation less favorable.

3. Steric Bulk and Accessibility:

As previously mentioned, significant steric hindrance can prevent a nucleophile from effectively approaching an electrophile. Even molecules with lone pairs and negative charges might be poor nucleophiles if their approach is blocked by bulky substituents. This explains why highly substituted tertiary amines are generally less nucleophilic than primary or secondary amines.

4. Transition Metal Complexes:

While some metal complexes can exhibit nucleophilic behavior, many are not considered nucleophiles in the traditional sense. Their reactivity is often governed by different factors, such as the oxidation state of the metal and the ligand field effects. The metal center's coordination environment significantly influences its reactivity.

Examples of Molecules that are NOT Typically Considered Nucleophiles:

Let's examine specific examples to solidify our understanding:

-

Alkenes and Alkynes: While they possess pi electrons, alkenes and alkynes typically behave as weak nucleophiles. Their reactions are usually more appropriately described as electrophilic additions. The pi electrons are involved in the formation of new sigma bonds, but the mechanism differs significantly from classical nucleophilic substitution reactions.

-

Aromatic Compounds: Benzene and its derivatives generally don't act as nucleophiles. The delocalized pi electrons in the aromatic ring are relatively unreactive towards electrophilic attack but are not readily donated. The exceptional stability of the aromatic system prevents nucleophilic attack.

-

Carbonyl Compounds (in their keto form): While the carbonyl oxygen has lone pairs, it's typically more prone to accepting electrons (acting as a weak electrophile) rather than donating them. The carbonyl carbon, however, can be an electrophile participating in nucleophilic addition reactions.

-

Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄): Sulfuric acid is a strong acid and a good electrophile due to its electron-deficient sulfur atom. It doesn't have any lone pairs readily available for donation.

-

Nitrogen gas (N₂): The triple bond in nitrogen gas makes it exceptionally unreactive. The electrons are tightly held within the strong triple bond, making nitrogen gas a very poor nucleophile.

Conclusion: A Deeper Understanding of Reactivity

Determining whether a molecule is a nucleophile requires a holistic assessment considering its charge, electronegativity, steric effects, and the surrounding environment. The presence of lone pairs is a necessary but not sufficient condition for nucleophilicity. Understanding the subtle interplay of these factors is essential for predicting reaction outcomes and designing efficient synthetic strategies in organic chemistry. The examples provided showcase the diverse factors that can drastically alter a molecule's ability to donate electrons and highlight the complex nature of reactivity in chemical systems. By comprehending these nuances, one can accurately identify molecules that defy the typical nucleophilic profile, furthering a more precise understanding of chemical transformations.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Is Boiling Water A Physical Change

Mar 17, 2025

-

Is A Webcam An Input Or Output Device

Mar 17, 2025

-

Word For A Person Who Uses Big Words

Mar 17, 2025

-

What Is 375 As A Percentage

Mar 17, 2025

-

Which Is The Correct Order Of The Scientific Method

Mar 17, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Which Of The Following Is Not A Nucleophile . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.