Virus Capsids Are Made From Subunits Called

News Leon

Mar 17, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Virus Capsids: Constructed from Subunits Called Capsomers

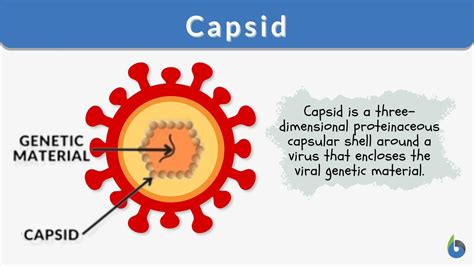

Viruses, those enigmatic entities blurring the line between living and non-living, rely on intricate structures for their survival and propagation. Central to this architecture is the capsid, a protein shell encasing the viral genome. Understanding how these capsids are built is crucial to comprehending viral assembly, infectivity, and ultimately, developing effective antiviral strategies. This article delves deep into the fascinating world of virus capsids, focusing on their fundamental building blocks: capsomers.

What are Capsomers?

Capsomers are the subunit proteins that self-assemble to form the capsid. These aren't simply random proteins; they possess specific structural features that allow them to interact precisely with each other, creating the highly organized and often symmetrical structures characteristic of viral capsids. Think of them as the individual bricks meticulously laid to construct a complex viral castle. The specific arrangement and number of capsomers determine the overall shape and size of the virus particle, or virion.

Types of Capsomers

While the fundamental role of capsomers remains consistent, their specific structures and interactions can vary. We can broadly categorize them based on their arrangement:

-

Pentons: These are capsomers with five-fold symmetry, forming the vertices or corners of many icosahedral capsids. They are crucial for initiating capsid assembly and providing structural stability. Think of them as the cornerstone of the viral building.

-

Hexons: Possessing six-fold symmetry, hexons make up the majority of the faces of icosahedral capsids. These are the "fillers," the bulk of the capsid structure, ensuring the overall integrity and strength.

Some viruses exhibit more complex capsid structures, necessitating additional types of capsomers to achieve their unique morphology. This highlights the remarkable diversity in viral design, dictated by their specific genomic and environmental requirements.

The Architecture of Viral Capsids: Symmetry and Structure

Viral capsids exhibit remarkable symmetry, primarily icosahedral or helical. This symmetry isn't just aesthetically pleasing; it's a highly efficient way to construct a stable, protective shell using a limited number of protein subunits.

Icosahedral Capsids

Icosahedral symmetry is prevalent among many viruses. An icosahedron is a 20-sided polyhedron with 12 vertices and 30 edges. This highly efficient arrangement allows for the construction of a closed shell using a relatively small number of capsomers. The precise number of capsomers is dictated by the specific virus but generally follows mathematical rules based on the icosahedral structure. The combination of pentons and hexons forms this stable and symmetrical structure. Examples include adenoviruses and many other animal viruses.

Helical Capsids

In contrast to the closed shell of icosahedral capsids, helical capsids form elongated, rod-like structures. These capsids are built by the helical arrangement of capsomer subunits around the viral nucleic acid. The subunits interact in a continuous, spiral fashion, creating a tube-like structure that encloses the genetic material. Tobacco mosaic virus is a classic example of a virus with a helical capsid.

Complex Capsids

Some viruses possess capsids that defy simple classification as purely icosahedral or helical. These complex capsids often incorporate additional structures, such as tails or other appendages, that aid in attachment and entry into host cells. Bacteriophages, viruses that infect bacteria, are a prime example, with their intricate head-tail structures. These complex capsids often combine aspects of icosahedral and helical symmetry, showcasing the remarkable versatility of viral design.

The Process of Capsid Assembly: Self-Assembly and Chaperones

The precise formation of the viral capsid is a remarkable feat of biological engineering. The process involves the self-assembly of capsomers, driven by the intrinsic properties of the protein subunits. This self-assembly is often facilitated by chaperone proteins, which assist in the correct folding and assembly of capsomer proteins, preventing aggregation and ensuring the proper formation of the capsid.

Self-Assembly: A Spontaneous Process

The remarkable aspect of capsid self-assembly is its spontaneity. Under the right conditions (appropriate pH, temperature, and ion concentration), the capsomer subunits spontaneously associate to form the characteristic capsid structure. This process is driven by non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and electrostatic forces, between the capsomer subunits.

The Role of Chaperones

While self-assembly is the driving force, it is not always a perfect, error-free process. Cellular chaperones, like those found in the endoplasmic reticulum and cytoplasm, can play a significant role in preventing aggregation of misfolded proteins and aiding in the correct folding and assembly of capsomers. This ensures the production of functional and structurally sound capsids.

The Significance of Capsomers in Viral Infection

Capsomers are not simply structural elements; they play critical roles in the viral life cycle, particularly in the process of infection:

-

Attachment to Host Cells: Specific regions on the capsomer surface, often forming receptor-binding sites, mediate the attachment of the virus to the host cell. These sites interact with specific receptors on the host cell surface, initiating the infection process.

-

Entry into Host Cells: After attachment, the virus must enter the host cell. The capsid plays a vital role in this process, either through direct penetration of the cell membrane, receptor-mediated endocytosis, or injection of the viral genome.

-

Protection of the Viral Genome: The capsid shields the viral genome from degradation by nucleases and other environmental factors, ensuring its safe passage to the host cell.

-

Uncoating and Genome Release: Once inside the host cell, the capsid must disassemble to release the viral genome. This process, known as uncoating, is often triggered by changes in pH or other environmental factors within the host cell.

Capsid Structure and Antiviral Strategies

The structure of the capsid, and specifically the arrangement of capsomers, represents a crucial target for antiviral strategies. Understanding the precise interactions between capsomers and the vulnerabilities in capsid structure opens avenues for the development of drugs that can:

-

Inhibit Capsid Assembly: Drugs designed to interfere with the self-assembly process, preventing the formation of functional capsids, could be highly effective antiviral agents.

-

Target Receptor-Binding Sites: Drugs targeting the receptor-binding sites on the capsomers could prevent the virus from attaching to and entering the host cell.

-

Promote Capsid Instability: Drugs that destabilize the capsid structure, promoting premature disassembly or preventing the release of the viral genome, could also be effective.

Capsid Diversity and Evolution

The diversity of viral capsids is astounding, reflecting the vast array of viruses infecting various organisms. This diversity arises from the evolutionary pressure to optimize the interactions with specific host cells and the environmental conditions. Mutations in capsomer genes can lead to changes in capsid structure, potentially affecting the virus's ability to infect host cells, its stability, and its overall virulence. This continuous adaptation and evolution shape the viral landscape, leading to the emergence of new viral strains and highlighting the importance of ongoing research in viral capsid biology.

Conclusion: Capsomers – The Building Blocks of Viral Infection

Capsomers, the fundamental subunits of viral capsids, are far more than just structural components. They are crucial players in the viral life cycle, from attachment to host cells to the release of the viral genome. A thorough understanding of their structure, assembly, and function is essential for developing effective antiviral strategies and comprehending the intricate dynamics of viral infection. The ongoing research in this field continuously unveils the complexity and sophistication of viral architecture, furthering our ability to combat these infectious agents. Further research into the intricate details of capsomer interactions, particularly concerning specific viruses, will continue to unlock new possibilities for therapeutic intervention and deepen our understanding of viral pathogenesis. The self-assembly mechanism, a marvel of nature’s engineering, remains a significant area of study, potentially offering insights into novel materials science and nanotechnology applications. The continued exploration of capsomer structure and function promises a wealth of knowledge applicable to both biological and technological advancements.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Boiling Water Physical Or Chemical Change

Mar 17, 2025

-

45 Is 60 Of What Number

Mar 17, 2025

-

What Is Larger Mg Or Mcg

Mar 17, 2025

-

0 3 To The Power Of 3

Mar 17, 2025

-

What Is 5 Percent Of 200

Mar 17, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Virus Capsids Are Made From Subunits Called . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.