The Pectoral Girdle Consists Of The:

News Leon

Mar 30, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

The Pectoral Girdle: A Deep Dive into its Structure, Function, and Clinical Significance

The human pectoral girdle, also known as the shoulder girdle, is a complex anatomical structure that plays a vital role in upper limb movement and overall body stability. Unlike the more robust pelvic girdle, the pectoral girdle prioritizes mobility over stability, allowing for a wide range of arm motions. This inherent flexibility, however, comes at the cost of increased susceptibility to injury. Understanding its components, their interrelationships, and potential vulnerabilities is crucial for both medical professionals and fitness enthusiasts.

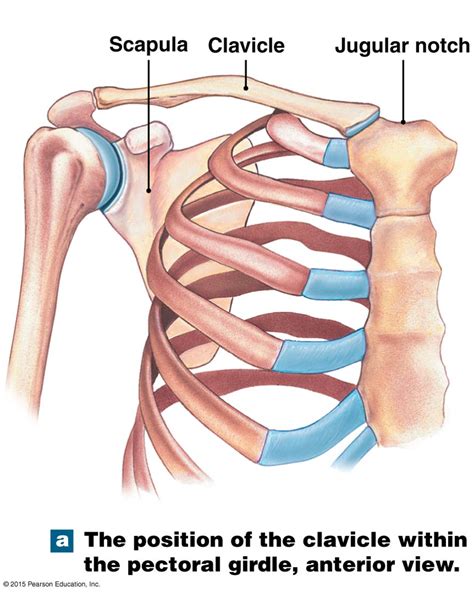

Components of the Pectoral Girdle: Clavicle and Scapula

The pectoral girdle is comprised of two major bones: the clavicle (collarbone) and the scapula (shoulder blade). These bones articulate with each other and with the humerus (upper arm bone) to form the shoulder joint, one of the most mobile joints in the human body. Let's delve deeper into each bone:

The Clavicle: A Strategic Link

The clavicle, an S-shaped bone, acts as a crucial strut connecting the axial skeleton (the skull and vertebral column) to the appendicular skeleton (the limbs). Its medial end articulates with the sternum (breastbone) at the sternoclavicular joint (SC joint), while its lateral end articulates with the acromion process of the scapula at the acromioclavicular joint (AC joint).

Key Functions of the Clavicle:

- Transmission of Forces: The clavicle effectively transmits forces from the upper limb to the axial skeleton, protecting the underlying neurovascular structures. It acts as a shock absorber, reducing the impact of forces transmitted through the arm.

- Maintaining Scapular Position: The clavicle helps to maintain the proper position of the scapula, preventing excessive medial or lateral displacement. This is vital for optimal shoulder function and stability.

- Range of Motion: By acting as a rigid strut, the clavicle allows for a wider range of motion in the shoulder joint. It prevents the scapula from being pulled too close to the spine, restricting movement.

Clinical Considerations of the Clavicle:

The clavicle's superficial location makes it particularly prone to fractures, especially in falls onto the outstretched hand. These fractures, often requiring medical intervention, can lead to significant pain, restricted mobility, and potential complications if not properly managed. Moreover, clavicular abnormalities can affect posture and shoulder function.

The Scapula: The Foundation of Shoulder Movement

The scapula, a flat, triangular bone, lies on the posterior aspect of the thorax, overlaying ribs 2-7. Its articulation with the clavicle and humerus contributes significantly to the shoulder's extensive range of motion. The scapula possesses several key features:

- Glenoid Cavity: This shallow, pear-shaped fossa on the lateral aspect of the scapula articulates with the head of the humerus, forming the glenohumeral joint (shoulder joint).

- Acromion Process: The acromion forms the highest point of the shoulder and articulates with the clavicle at the AC joint.

- Coracoid Process: This hook-like projection serves as an attachment point for several muscles, contributing to shoulder stability and movement.

- Spine of the Scapula: A prominent ridge running across the posterior surface of the scapula, providing attachment sites for various muscles.

- Superior, Medial, and Inferior Borders: These define the overall shape and boundaries of the scapula.

Key Functions of the Scapula:

- Stabilizing the Shoulder Joint: The scapula provides a stable base for the glenohumeral joint, allowing for precise and controlled movements.

- Enhancing Range of Motion: Through its articulation with the clavicle and humerus, the scapula facilitates a wide range of arm movements, including flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, and rotation.

- Muscle Attachment: The scapula serves as an attachment point for numerous muscles responsible for shoulder and arm movement, including the trapezius, rhomboids, serratus anterior, and deltoids.

Clinical Considerations of the Scapula:

Scapular injuries are less common than clavicular fractures but can still occur, often due to direct trauma or repetitive strain. Conditions such as scapular winging (where the medial border of the scapula protrudes), can arise from nerve damage affecting muscles that stabilize the scapula.

Muscles of the Pectoral Girdle: Orchestrating Movement

The pectoral girdle's mobility relies heavily on the complex interplay of several muscle groups. These muscles, originating from various parts of the axial skeleton and inserting onto the clavicle and scapula, enable a wide range of movements and contribute significantly to shoulder stability.

Key Muscle Groups:

- Trapezius: A large superficial muscle extending from the occipital bone to the thoracic vertebrae and inserting onto the clavicle and scapula. Its functions include elevation, depression, retraction, and upward rotation of the scapula.

- Rhomboids (Major and Minor): Deep muscles located beneath the trapezius, responsible for retraction and downward rotation of the scapula.

- Levator Scapulae: Elevates the scapula and slightly rotates it.

- Serratus Anterior: A muscle originating from the ribs and inserting onto the medial border of the scapula. Its primary function is protraction and upward rotation of the scapula.

- Pectoralis Minor: Located deep to the pectoralis major, it depresses and protracts the scapula.

- Subclavius: A small muscle connecting the clavicle to the first rib, stabilizing the clavicle and depressing the shoulder.

Clinical Considerations of Pectoral Girdle Muscles:

Muscle imbalances, strains, and tears are common pectoral girdle injuries, often resulting from overuse, improper lifting techniques, or sudden trauma. Weakness in specific muscle groups can lead to postural abnormalities and increased risk of shoulder instability. Conditions like rotator cuff injuries, affecting muscles surrounding the glenohumeral joint, are also frequently encountered.

Joints of the Pectoral Girdle: Mobility and Stability

The smooth, coordinated movement of the pectoral girdle relies on the intricate interplay of three crucial joints:

1. Sternoclavicular Joint (SC Joint):

This joint, connecting the medial end of the clavicle to the sternum, is a saddle-type synovial joint. It allows for a combination of movements: elevation/depression, protraction/retraction, and rotation of the clavicle. This joint’s stability is crucial for overall shoulder function.

2. Acromioclavicular Joint (AC Joint):

This joint, where the lateral end of the clavicle articulates with the acromion process of the scapula, is also a synovial joint. It allows for limited gliding movements, contributing to scapular rotation and overall shoulder mobility. AC joint injuries, often sprains or separations, are common in contact sports.

3. Glenohumeral Joint (Shoulder Joint):

While not strictly part of the pectoral girdle itself, the glenohumeral joint is inextricably linked to its function. This ball-and-socket joint, formed by the articulation of the humeral head with the glenoid cavity of the scapula, is responsible for the remarkable range of motion in the shoulder. Its stability is maintained by surrounding ligaments, tendons, and muscles of the rotator cuff.

Clinical Significance and Common Injuries

The pectoral girdle's high degree of mobility renders it vulnerable to various injuries and conditions:

- Clavicular Fractures: Common, especially in falls.

- Acromioclavicular (AC) Joint Separations: Range from mild sprains to severe dislocations.

- Rotator Cuff Injuries: Tears or impingement of the rotator cuff muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis).

- Shoulder Dislocations: Displacement of the humeral head from the glenoid cavity.

- Scapular Winging: Medial border of the scapula protrudes due to serratus anterior muscle weakness.

- Frozen Shoulder (Adhesive Capsulitis): Characterized by stiffness and pain in the shoulder joint.

- Bursitis: Inflammation of the bursae, fluid-filled sacs that cushion the shoulder joint.

- Tendinitis: Inflammation of the tendons surrounding the shoulder joint.

Importance of Maintaining Pectoral Girdle Health

Maintaining pectoral girdle health is crucial for optimal upper limb function and overall well-being. Regular exercise, proper posture, and injury prevention strategies are essential. Strengthening the muscles supporting the shoulder girdle can improve stability and reduce the risk of injury. Activities like swimming, rowing, and weight training can effectively strengthen these muscles. Furthermore, maintaining good posture helps to prevent muscle imbalances and strain. Seeking professional help for any persistent shoulder pain or discomfort is essential for accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

This comprehensive overview of the pectoral girdle details its intricate structure, function, and clinical significance. Understanding this vital anatomical region is crucial for maintaining optimal upper limb function, preventing injury, and addressing any health concerns promptly and effectively. By recognizing the interconnectedness of bones, muscles, and joints, we can appreciate the remarkable mobility and vulnerability of the human shoulder girdle.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Did David Used To Kill Goliath

Apr 01, 2025

-

Are Cells Depicted Plant Or Animal

Apr 01, 2025

-

Select Which Statements Are A Part Of Natural Selection

Apr 01, 2025

-

Why Electronic Configuration Of Calcium Is 2 8 8 2

Apr 01, 2025

-

1 Square Meter Is How Many Square Centimeters

Apr 01, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about The Pectoral Girdle Consists Of The: . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.