Only Moveable Bone In The Skull

News Leon

Mar 19, 2025 · 8 min read

Table of Contents

The Only Moveable Bone in the Skull: A Deep Dive into the Mandible

The human skull, a complex structure of interconnected bones, provides crucial protection for the brain and houses our sensory organs. While most of the skull's bones are firmly fused together, creating a rigid framework, one bone stands apart: the mandible, also known as the jawbone. This article delves deep into the fascinating anatomy, function, and clinical significance of this unique, moveable bone in the skull.

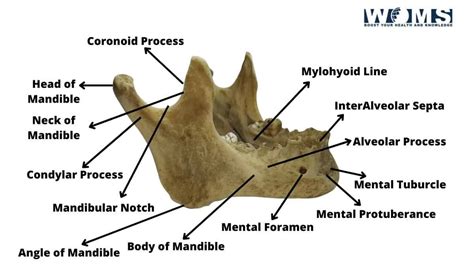

The Mandible: A Closer Look at its Unique Anatomy

Unlike the other cranial bones, which are interconnected by sutures (immovable joints), the mandible articulates with the temporal bones of the skull via the temporomandibular joints (TMJs). This unique articulation allows for a wide range of movements, essential for crucial functions like chewing, speaking, and swallowing.

Distinctive Features of the Mandible:

- Body: The horizontal portion of the mandible, forming the chin and lower jawline. The mental foramen, a small opening on the anterior surface of the body, allows passage for the mental nerve and vessels.

- Ramus: The vertical portion of the mandible, extending upward from the body on each side. It features two processes:

- Condylar Process: The posterior process, articulating with the temporal bone at the TMJ. Its smooth articular surface, the mandibular condyle, is crucial for jaw movement.

- Coronoid Process: The anterior process, serving as an attachment point for the temporalis muscle, a major muscle involved in chewing.

- Angle: The area where the body and ramus meet, forming a characteristic angle that varies slightly between individuals.

- Alveolar Process: The thickened portion of the mandible that houses the lower teeth. This process is crucial for supporting the teeth and providing stable attachment for the periodontal ligaments.

The mandible's robust structure is vital for its role in mastication (chewing). The shape and arrangement of its processes, the powerful muscles attached to it, and its articulation with the temporal bone are all finely tuned for efficient and forceful jaw movement.

The Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ): The Key to Mandible Mobility

The TMJ is not just a simple hinge joint; it's a complex synovial joint, characterized by a unique articulation between the mandibular condyle and the temporal bone. This unique articulation allows for a combination of hinge and gliding movements, contributing to the mandible's remarkable range of motion.

Components of the TMJ:

- Articular Disc: A fibrocartilaginous disc that separates the mandibular condyle from the temporal bone, dividing the joint into two compartments: the upper and lower synovial cavities. This disc plays a crucial role in cushioning and distributing forces during jaw movement.

- Articular Eminence: A bony projection on the temporal bone, contributing to the gliding movements of the mandible.

- Glenoid Fossa: A shallow depression on the temporal bone, forming part of the articular surface for the mandibular condyle.

- Ligaments: Several ligaments surrounding the TMJ provide stability and limit excessive movement, preventing dislocation and injury. These include the temporomandibular ligament, sphenomandibular ligament, and stylomandibular ligament.

The intricate interaction between these components enables the mandible to perform a wide variety of movements, including:

- Elevation: Closing the mouth.

- Depression: Opening the mouth.

- Protrusion: Moving the jaw forward.

- Retrusion: Moving the jaw backward.

- Lateral Deviation: Moving the jaw side to side.

Understanding the biomechanics of the TMJ is crucial for diagnosing and treating temporomandibular disorders (TMDs), a common group of conditions affecting the jaw and surrounding muscles.

The Muscles of Mastication: Powering Mandible Movement

The movement of the mandible is controlled by a group of powerful muscles, collectively known as the muscles of mastication. These muscles work in coordinated fashion, enabling the precise and forceful movements required for chewing, speaking, and swallowing.

Key Muscles of Mastication:

- Masseter: A powerful muscle located on the side of the face, responsible for elevating the mandible (closing the mouth). Its strong contractions generate the force needed for chewing tough foods.

- Temporalis: A fan-shaped muscle originating from the temporal fossa and inserting onto the coronoid process of the mandible. It contributes significantly to the elevation and retraction of the mandible.

- Medial Pterygoid: A deep muscle located within the infratemporal fossa. It works in synergy with the masseter muscle to elevate the mandible and also contributes to protrusion.

- Lateral Pterygoid: This muscle has two heads, and plays a crucial role in protrusive and lateral movements of the mandible. It also assists in depressing the mandible (opening the mouth).

The coordinated action of these muscles allows for the complex movements necessary for efficient mastication. Muscle imbalances or dysfunction can lead to various problems, including temporomandibular joint disorders (TMDs).

Clinical Significance of the Mandible and TMJ

The mandible and TMJ are prone to a variety of disorders, collectively known as temporomandibular disorders (TMDs). These conditions can range from mild discomfort to severe pain and functional limitations.

Common Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs):

- TMJ Pain: Pain in the TMJ itself, often characterized by a dull ache or sharp pain.

- Myofascial Pain: Pain originating in the muscles of mastication, often associated with muscle tension or spasms.

- Joint Clicks or Pops: Audible or palpable clicks or pops during jaw movement, often indicative of disc displacement within the TMJ.

- Limited Jaw Opening: Difficulty opening the mouth wide, sometimes severe enough to restrict eating or speaking.

- Locking of the Jaw: The inability to open or close the mouth properly.

- Temporomandibular Joint Arthritis: Degenerative changes in the TMJ, causing pain and inflammation.

The diagnosis and management of TMDs typically involve a combination of clinical examination, imaging studies (such as X-rays or MRI), and patient history. Treatment options vary depending on the severity of the condition and may include conservative measures such as pain management, physical therapy, and bite splints, or more invasive approaches such as surgery in severe cases.

The Mandible in Forensic Science and Anthropology

The mandible's unique characteristics also make it invaluable in fields like forensic science and anthropology. The shape, size, and features of the mandible can provide crucial information for identifying individuals and understanding their ancestry and lifestyle.

Forensic and Anthropological Applications:

- Identification: The mandible's distinct morphology, including the shape of the chin, the angle of the ramus, and the arrangement of teeth, can be used to identify individuals in forensic investigations.

- Sex Determination: Certain features of the mandible, such as the size and shape of the chin and the angle of the ramus, can be used to determine the sex of an individual.

- Age Estimation: The degree of tooth wear, the development of bony features, and the presence of degenerative changes can provide clues about the age of an individual.

- Ancestry Determination: Variations in the shape and size of the mandible can be linked to different ancestral groups, providing valuable information in anthropological studies.

The study of the mandible in forensic and anthropological contexts plays a significant role in solving crimes, piecing together historical records, and furthering our understanding of human evolution and diversity.

The Mandible's Role in Speech and Swallowing

Beyond its primary role in mastication, the mandible plays crucial supporting roles in speech and swallowing. Its precise and controlled movements are essential for the production of distinct sounds and the coordinated process of swallowing.

Speech Production:

The mandible's movements are essential for shaping the vocal tract and producing various speech sounds. Its positioning influences the resonance characteristics of the vocal tract, influencing the production of vowels and consonants. Precise control over the mandible is crucial for clear and articulate speech.

Swallowing (Deglutition):

The mandible plays a crucial part in the initial stages of swallowing, where it helps to manipulate food into a bolus and initiate its movement toward the pharynx. Its coordinated movements with the tongue and other structures of the oral cavity ensure safe and efficient swallowing. Disorders affecting mandibular function can impair swallowing, potentially leading to aspiration pneumonia and other complications.

Developmental Aspects of the Mandible

The development of the mandible is a complex process involving the interaction of multiple genetic and environmental factors. Its formation begins early in embryonic development and continues throughout childhood and adolescence.

Mandibular Development:

The mandible develops from the first branchial arch, initially as a cartilaginous structure that later undergoes ossification to form the bony mandible. The process of ossification involves the formation of multiple ossification centers, which eventually fuse together to form a single bone. The growth of the mandible is influenced by several factors, including genetics, hormones, and masticatory function. Malocclusions (misalignments of teeth) and other developmental anomalies can affect the shape and growth of the mandible.

Understanding mandibular development is crucial for diagnosing and treating craniofacial anomalies in children, such as cleft palate and other developmental conditions.

Conclusion: The Unsung Hero of the Skull

The mandible, the only moveable bone in the skull, is far more than just a jawbone. Its unique anatomy, intricate articulation with the temporal bone, and coordinated action with powerful muscles contribute to essential functions like chewing, speaking, and swallowing. Its clinical significance is highlighted by the prevalence of temporomandibular disorders (TMDs), while its importance in forensic science and anthropology underscores its value in human identification and understanding. The continued study of this fascinating bone promises further insights into its complex roles and clinical implications. From its robust structure to its precise movements, the mandible truly deserves recognition as a remarkable and crucial component of the human skull.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Which Of The Following Antibodies Is A Pentamer

Mar 19, 2025

-

What Is The River Behind The Taj Mahal

Mar 19, 2025

-

Why Is The Heart Called A Double Pump

Mar 19, 2025

-

What Percentage Of 8 Is 64

Mar 19, 2025

-

How Many Pints In One Pound

Mar 19, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Only Moveable Bone In The Skull . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.