Kinetic Energy Of Simple Harmonic Motion

News Leon

Mar 23, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Kinetic Energy of Simple Harmonic Motion: A Deep Dive

Simple harmonic motion (SHM) is a fundamental concept in physics, describing the oscillatory motion of a system around a stable equilibrium position. Understanding the energy dynamics within SHM, specifically the kinetic energy, is crucial for grasping its behavior and applications. This comprehensive guide delves into the kinetic energy of SHM, exploring its relationship with potential energy, total energy, and various examples.

Understanding Simple Harmonic Motion

Before diving into the kinetic energy, let's solidify our understanding of SHM. SHM is characterized by a restoring force directly proportional to the displacement from the equilibrium position and directed towards it. Mathematically, this is represented as:

F = -kx

where:

- F is the restoring force

- k is the spring constant (a measure of the stiffness of the system)

- x is the displacement from the equilibrium position

This relationship leads to a sinusoidal oscillation, with the system's position, velocity, and acceleration varying periodically. Common examples include a mass on a spring, a simple pendulum (for small angles), and the oscillation of atoms in a crystal lattice.

Kinetic Energy in SHM: The Basics

The kinetic energy (KE) of any object is given by:

KE = ½mv²

where:

- m is the mass of the object

- v is its velocity

In SHM, the velocity is not constant but varies sinusoidally with time. This means the kinetic energy also changes continuously throughout the oscillation. At the equilibrium position (x=0), the velocity is maximum, resulting in maximum kinetic energy. Conversely, at the extreme points of the oscillation (maximum displacement), the velocity is zero, and the kinetic energy is zero.

The Relationship Between Kinetic and Potential Energy in SHM

In a conservative system like SHM (ignoring energy losses due to friction or air resistance), the total mechanical energy remains constant. This total energy is the sum of the kinetic energy (KE) and potential energy (PE):

Total Energy (E) = KE + PE

For a system exhibiting SHM, such as a mass on a spring, the potential energy is given by:

PE = ½kx²

Therefore, the total energy is:

E = ½mv² + ½kx²

This equation highlights the crucial interplay between kinetic and potential energy in SHM. As the kinetic energy increases, the potential energy decreases, and vice versa. The total energy remains constant, transferring back and forth between kinetic and potential forms throughout the oscillation.

Analyzing Energy Transformations

Let's visualize the energy transformation during one complete oscillation:

-

Maximum Displacement: At the extreme points of the oscillation, the velocity is zero (v=0), thus KE = 0. The potential energy is at its maximum (PE = ½kA², where A is the amplitude). All the energy is stored as potential energy.

-

Equilibrium Position: As the mass moves towards the equilibrium position, the potential energy decreases as the displacement decreases. Simultaneously, the velocity increases, causing the kinetic energy to increase. At the equilibrium position (x=0), the velocity is maximum (v=vmax), and the kinetic energy reaches its maximum value (KE = ½mvmax²). The potential energy is zero.

-

Opposite Maximum Displacement: The mass continues past the equilibrium position, eventually reaching the opposite extreme point of its oscillation. The process reverses: kinetic energy decreases to zero, and potential energy increases to its maximum value again.

This cycle repeats continuously, with the total energy remaining constant. This conservation of energy is a defining characteristic of SHM.

Calculating Kinetic Energy at Specific Points

To calculate the kinetic energy at a specific point in the oscillation, we need to determine the velocity at that point. The velocity in SHM can be expressed as a function of time:

v(t) = -ωA sin(ωt + φ)

where:

- ω is the angular frequency (ω = √(k/m))

- A is the amplitude of the oscillation

- t is the time

- φ is the phase constant

Substituting this into the kinetic energy equation, we get:

KE(t) = ½mω²A²sin²(ωt + φ)

This equation allows us to calculate the kinetic energy at any given time during the oscillation. Similarly, we can express the velocity in terms of displacement:

v = ±ω√(A² - x²)

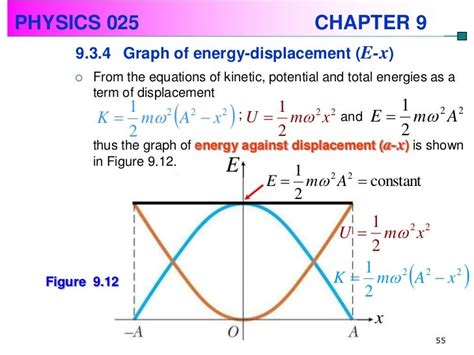

And the kinetic energy as a function of displacement:

KE(x) = ½mω²(A² - x²)

This equation directly relates the kinetic energy to the displacement from the equilibrium position.

Examples of Kinetic Energy in SHM

Several real-world examples demonstrate the principles of kinetic energy in SHM:

-

Mass-Spring System: A mass attached to a spring exhibits classic SHM. The kinetic energy is maximum when the mass passes through the equilibrium point and zero at the points of maximum displacement.

-

Simple Pendulum (Small Angles): For small angles, a simple pendulum approximates SHM. The kinetic energy is maximum at the bottom of the swing (equilibrium position) and zero at the highest points of the swing.

-

Molecular Vibrations: Atoms in molecules vibrate around their equilibrium positions, exhibiting SHM. The kinetic energy associated with these vibrations contributes to the thermal energy of the substance.

-

LC Circuits: In an ideal LC circuit (an inductor and a capacitor), the energy oscillates between the magnetic energy stored in the inductor and the electric energy stored in the capacitor, analogous to the kinetic and potential energy in SHM.

Factors Affecting Kinetic Energy in SHM

Several factors influence the kinetic energy in SHM:

-

Mass (m): A larger mass leads to a higher kinetic energy at any given velocity.

-

Amplitude (A): A larger amplitude results in a greater maximum velocity and thus a higher maximum kinetic energy.

-

Spring Constant (k): A stiffer spring (larger k) leads to a higher angular frequency (ω), resulting in a faster oscillation and higher maximum kinetic energy for a given amplitude.

-

Velocity (v): The kinetic energy is directly proportional to the square of the velocity.

Damped Simple Harmonic Motion and Kinetic Energy

Real-world SHM systems are often subject to damping forces, such as friction or air resistance. These forces dissipate energy, reducing the amplitude of the oscillation over time. In damped SHM, the total energy is not conserved; the kinetic energy is gradually converted into thermal energy through the damping force. The equations become more complex, involving exponential decay terms.

Forced Oscillations and Resonance

When an external periodic force is applied to a system undergoing SHM, it experiences forced oscillations. If the frequency of the external force matches the natural frequency of the system, resonance occurs. During resonance, the amplitude of the oscillation dramatically increases, leading to a substantial increase in the maximum kinetic energy. This phenomenon has both practical applications (e.g., musical instruments) and potential dangers (e.g., bridge collapses due to resonant vibrations).

Conclusion

The kinetic energy of simple harmonic motion is a crucial aspect of understanding the oscillatory behavior of numerous physical systems. Its continuous transformation with potential energy, governed by the principles of energy conservation (in ideal systems), provides a fundamental insight into the dynamics of SHM. Understanding the factors that influence kinetic energy and the effects of damping and forced oscillations are essential for comprehending real-world applications and potential challenges related to SHM. From the seemingly simple mass-spring system to complex molecular vibrations, the principles explored here provide a foundation for a deeper appreciation of the physics behind oscillatory motion. Further exploration of more advanced concepts, such as Lagrangian and Hamiltonian mechanics, can offer even deeper insights into the energy dynamics of SHM.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

The Figure Shows A Rectangular 20 Turn Coil Of Wire

Mar 25, 2025

-

A Group Of 8 Bits Is Called

Mar 25, 2025

-

85 Is 80 Of What Number

Mar 25, 2025

-

What Does A Pyramid Of Biomass Represent

Mar 25, 2025

-

Group Of Cells Working Together Is Called

Mar 25, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Kinetic Energy Of Simple Harmonic Motion . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.