In The Figure A Particle Moves Along A Circle

News Leon

Mar 20, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

Unveiling the Mysteries of Circular Motion: A Deep Dive into Particle Dynamics

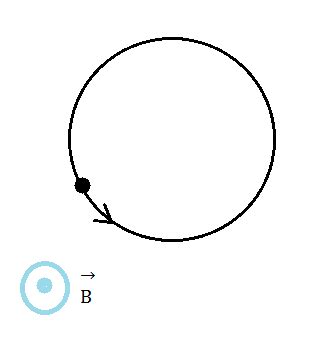

The seemingly simple image of a particle moving along a circle belies a rich tapestry of physics principles. Understanding this seemingly straightforward scenario unlocks the door to comprehending a vast array of phenomena, from planetary orbits to the behavior of electrons in atoms. This comprehensive exploration delves into the intricacies of circular motion, examining its key concepts, mathematical descriptions, and real-world applications.

Defining Circular Motion: Beyond the Simple Circle

Circular motion, at its core, describes the movement of a particle along a circular path. However, this seemingly simple definition hides a multitude of nuances. We must distinguish between uniform circular motion and non-uniform circular motion.

-

Uniform Circular Motion (UCM): This is the idealized case where the particle moves at a constant speed along the circular path. While the speed remains constant, the velocity is constantly changing because the direction of motion is continuously altering. This change in velocity signifies acceleration, known as centripetal acceleration.

-

Non-Uniform Circular Motion: Here, the particle's speed along the circular path varies with time. In addition to centripetal acceleration, there's also a tangential acceleration component responsible for the change in speed. This makes the analysis significantly more complex.

The Cornerstone Concepts: Speed, Velocity, and Acceleration

To fully grasp circular motion, a firm understanding of speed, velocity, and acceleration is paramount.

-

Speed (v): This scalar quantity represents the rate at which the particle covers distance along the circular path. In UCM, speed remains constant.

-

Velocity (v): This vector quantity incorporates both speed and direction. Even in UCM, velocity is constantly changing because the direction of motion is continuously tangential to the circle.

-

Acceleration (a): The rate of change of velocity. In circular motion, acceleration is always directed towards the center of the circle – this is centripetal acceleration (a<sub>c</sub>). It's responsible for constantly redirecting the particle's velocity to keep it moving in a circle. In non-uniform circular motion, an additional tangential acceleration (a<sub>t</sub>) component appears, acting tangent to the circle and responsible for changes in the particle's speed.

Mathematical Formulation: Unveiling the Equations

The mathematical description of circular motion relies heavily on vector calculus and trigonometry. Let's explore the key equations for both uniform and non-uniform circular motion.

Uniform Circular Motion (UCM)

-

Centripetal Acceleration: The magnitude of centripetal acceleration is given by:

a<sub>c</sub> = v²/r

where:

vis the speed of the particleris the radius of the circular path

-

Angular Velocity (ω): This describes the rate of change of angular displacement (θ) and is given by:

ω = Δθ/Δt or, in UCM, ω = v/r

-

Period (T): The time taken to complete one full revolution:

T = 2πr/v = 2π/ω

-

Frequency (f): The number of revolutions per unit time:

f = 1/T = ω/2π

Non-Uniform Circular Motion

Introducing tangential acceleration complicates matters. Now we have two acceleration components:

-

Tangential Acceleration (a<sub>t</sub>): This component is responsible for changes in the particle's speed. It's given by the rate of change of speed:

a<sub>t</sub> = dv/dt

-

Total Acceleration (a): The total acceleration is the vector sum of centripetal and tangential acceleration:

a = √(a<sub>c</sub>² + a<sub>t</sub>²)

The direction of the total acceleration is neither purely radial nor purely tangential but lies somewhere in between.

Forces in Circular Motion: The Role of Centripetal Force

A particle undergoing circular motion doesn't maintain its trajectory by itself. An external force, known as centripetal force, is always required to provide the necessary centripetal acceleration. This force is always directed towards the center of the circle.

Examples of centripetal forces include:

- Gravity: Keeps planets in orbit around the sun.

- Tension: In a rotating object tied to a string, the tension in the string provides the centripetal force.

- Friction: Allows a car to turn a corner.

- Electromagnetic Force: Keeps electrons orbiting the nucleus in an atom.

Real-World Applications: From Ferris Wheels to Satellites

The principles of circular motion are fundamental to countless real-world applications:

-

Planetary Orbits: The gravitational force between a planet and the sun acts as the centripetal force, keeping planets in their elliptical (or nearly circular) orbits.

-

Satellite Motion: Satellites orbiting the Earth are maintained in their orbits by the Earth's gravitational pull, acting as the centripetal force.

-

Roller Coasters: The combination of gravity and track design provides the centripetal force that keeps the roller coaster cars on the track during loops and turns.

-

Rotating Machines: From centrifuges separating components to car tires gripping the road, the principles of circular motion are crucial in understanding how these systems function.

-

Particle Accelerators: These devices use powerful electromagnetic fields to accelerate charged particles in circular paths, enabling research into fundamental physics.

Advanced Concepts: Beyond the Basics

For a more complete understanding, we can delve into more advanced concepts:

-

Angular Momentum: A measure of rotational inertia, crucial for understanding the conservation of rotational motion.

-

Moment of Inertia: Relates to the distribution of mass in a rotating object, influencing its rotational behavior.

-

Rotating Frames of Reference: Analyzing circular motion from a rotating frame introduces fictitious forces like the Coriolis effect, which explains phenomena like the deflection of moving objects on Earth.

-

Relativistic Circular Motion: At extremely high speeds, approaching the speed of light, relativistic effects need to be considered, modifying the equations of motion.

Conclusion: A Journey into the Heart of Circular Motion

The study of a particle moving along a circle, while seemingly simple at first glance, unveils a fascinating world of physics principles. From the basic concepts of speed, velocity, and acceleration to the more advanced topics of angular momentum and relativistic effects, understanding circular motion provides a foundation for comprehending a vast range of phenomena in our universe. This intricate interplay of forces, accelerations, and mathematical descriptions reveals the elegant precision governing the movement of objects in circular paths, highlighting the fundamental elegance and power of physics. The exploration presented here merely scratches the surface of this rich and rewarding area of study, encouraging further investigation and a deeper appreciation of the principles that govern the physical world around us. The journey into the heart of circular motion is a continuous exploration, revealing new insights and applications with every step.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

As A Runaway Scientific Balloon Ascends

Mar 21, 2025

-

1000 Days In Years And Months

Mar 21, 2025

-

A Thin Circular Disk Of Radius R

Mar 21, 2025

-

A Movement That Decreases A Joint Angle Is Called

Mar 21, 2025

-

X 3 3x 2 X 3 Factor

Mar 21, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about In The Figure A Particle Moves Along A Circle . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.