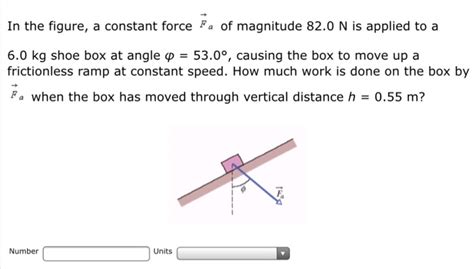

In The Figure A Constant Force Fa Of Magnitude

News Leon

Mar 21, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

- In The Figure A Constant Force Fa Of Magnitude

- Table of Contents

- Decoding the Constant Force: A Deep Dive into the Physics of Fₐ

- Understanding Constant Force (Fₐ)

- Newton's Second Law and Constant Force

- Calculating Work Done by a Constant Force

- Potential Energy and Constant Force

- Kinetic Energy and Constant Force

- Examples of Constant Force in Real-World Scenarios

- Challenges and Limitations of the Constant Force Model

- Advanced Concepts and Further Exploration

- Conclusion

- Latest Posts

- Latest Posts

- Related Post

Decoding the Constant Force: A Deep Dive into the Physics of Fₐ

In physics, understanding forces is fundamental. This article delves into the intricacies of a constant force, denoted as Fₐ, exploring its implications in various scenarios. We'll analyze its effects on motion, work done, and energy transfer, offering a comprehensive understanding accessible to both students and enthusiasts alike.

Understanding Constant Force (Fₐ)

A constant force is a force that maintains a constant magnitude and direction throughout its application. Unlike variable forces (like friction or spring forces), Fₐ remains unchanged irrespective of the object's position or velocity. This simplifies many calculations and allows for a clear understanding of fundamental principles. Imagine pushing a heavy box across a frictionless floor; the force you apply, if consistent, would be an example of Fₐ. The key characteristics are:

- Constant Magnitude: The strength of the force remains the same. A constant force of 10 Newtons will always exert 10 Newtons, regardless of the displacement.

- Constant Direction: The direction of the force doesn't change. It acts along the same line throughout the duration of its application.

Newton's Second Law and Constant Force

Newton's Second Law of Motion, F = ma, provides the cornerstone for understanding the effects of a constant force on an object's motion. Here, F represents the net force acting on the object, m is the object's mass, and a is its acceleration. If Fₐ is the only force acting on an object, then:

Fₐ = ma

This equation directly links the constant force to the object's acceleration. Crucially, a constant force produces a constant acceleration. This leads to predictable changes in velocity and displacement.

Implications of Constant Acceleration:

- Linear Velocity Change: The velocity of the object changes linearly with time. The change in velocity is directly proportional to the force and inversely proportional to the mass.

- Quadratic Displacement: The object's displacement (change in position) varies quadratically with time. This means the distance covered increases significantly over time under the influence of a constant force.

Calculating Work Done by a Constant Force

Work, in physics, represents the energy transferred to or from an object via the application of a force along a displacement. For a constant force, the work done (W) is calculated using the dot product:

W = Fₐ • d = |Fₐ| |d| cosθ

Where:

- |Fₐ| is the magnitude of the constant force.

- |d| is the magnitude of the displacement.

- θ is the angle between the force vector and the displacement vector.

Important Considerations:

- Direction Matters: If the force and displacement are in the same direction (θ = 0°), the work done is positive, indicating energy transfer to the object (e.g., accelerating it). If they are opposite (θ = 180°), the work is negative, meaning energy is transferred from the object (e.g., decelerating it). If they are perpendicular (θ = 90°), no work is done.

- Scalar Quantity: Work is a scalar quantity, meaning it has magnitude but no direction. It represents the total energy transferred.

Potential Energy and Constant Force

Constant forces often lead to changes in potential energy. Consider the classic example of lifting an object vertically against gravity. Gravity is a constant force (near the Earth's surface). The work done against gravity increases the object's gravitational potential energy:

ΔPE = mgh

Where:

- m is the object's mass.

- g is the acceleration due to gravity (approximately 9.8 m/s²).

- h is the vertical displacement.

This potential energy can be converted back into kinetic energy when the object falls.

Kinetic Energy and Constant Force

The work done by a constant force also changes an object's kinetic energy. The work-energy theorem states that the net work done on an object equals its change in kinetic energy:

W = ΔKE = ½mv² - ½mu²

Where:

- v is the final velocity.

- u is the initial velocity.

For a constant force, we can use this theorem to directly relate the force, displacement, and the resulting change in velocity.

Examples of Constant Force in Real-World Scenarios

Numerous real-world scenarios involve constant forces, although often with approximations. Some prominent examples include:

- Pushing/Pulling on a frictionless surface: As mentioned earlier, pushing a box across a frictionless surface exemplifies a constant force. This idealized scenario ignores friction, making the force constant.

- Weight: The force of gravity on an object near the Earth's surface is considered constant, provided the object doesn't move to a significantly different altitude.

- Electrostatic force (in specific contexts): The force between two point charges is constant if the distance between them remains constant.

- Magnetic force (under specific conditions): In certain situations, the magnetic force on a moving charge in a uniform magnetic field can be considered constant.

Challenges and Limitations of the Constant Force Model

While the constant force model is highly useful for simplifying calculations and understanding fundamental principles, it's crucial to acknowledge its limitations:

- Idealization: Many real-world forces are not truly constant. Friction, air resistance, and spring forces, for example, are variable forces that depend on factors like velocity or displacement.

- Limited Applicability: The constant force model is best applied to situations where the force's magnitude and direction remain relatively unchanged over the relevant time and distance.

- Ignoring other forces: Applying the constant force model often requires ignoring or minimizing the influence of other forces present in the system.

Advanced Concepts and Further Exploration

For a deeper understanding, one can explore more advanced concepts related to constant forces:

- Impulse and Momentum: The impulse-momentum theorem connects the force applied over a time interval to the change in momentum of an object. For a constant force, this simplifies the calculation of momentum change.

- Vectors and Force Decomposition: When dealing with forces acting at angles, vector decomposition becomes crucial to understand the components of the force contributing to work and acceleration.

- Systems of Particles and Multiple Forces: Analyzing systems with multiple constant forces acting on different objects requires applying Newton's laws to each object individually and considering the interactions between them.

Conclusion

The concept of a constant force, Fₐ, is a powerful tool for understanding basic mechanics. Its consistent magnitude and direction simplify calculations related to acceleration, work, energy, and momentum. While idealized, this model provides a valuable foundation for tackling more complex scenarios involving variable forces. By understanding its limitations and exploring advanced concepts, we can effectively apply the principles of constant force to solve a wide range of physics problems, paving the way for deeper explorations in dynamics and other related fields. Remember, mastering the fundamentals of constant force is key to unlocking a richer understanding of the intricate world of physics.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Kinetic Energy Of Simple Harmonic Motion

Mar 23, 2025

-

Whats The Closest Planet To The Moon

Mar 23, 2025

-

The Is The Basic Unit Of Life

Mar 23, 2025

-

17 Is What Percent Of 50

Mar 23, 2025

-

How To Draft An Invitation Letter

Mar 23, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about In The Figure A Constant Force Fa Of Magnitude . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.