In Meiosis Homologous Chromosomes Separate During

News Leon

Mar 19, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

In Meiosis, Homologous Chromosomes Separate During Meiosis I: A Deep Dive into the Process

Meiosis is a specialized type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, creating four haploid cells from a single diploid cell. This process is crucial for sexual reproduction, ensuring genetic diversity in offspring. A key event in meiosis is the separation of homologous chromosomes, a process that occurs during Meiosis I. Understanding this separation is fundamental to comprehending the entire meiotic process and its significance in genetics.

The Significance of Homologous Chromosome Separation in Meiosis I

Before delving into the mechanics, let's establish the importance of homologous chromosome separation. Diploid cells, like those in most human somatic cells, contain two sets of chromosomes – one inherited from each parent. These chromosome pairs, one maternal and one paternal, are called homologous chromosomes. They carry the same genes, but may possess different versions of those genes, called alleles.

The separation of homologous chromosomes during Meiosis I is critical because it ensures that each resulting gamete (sperm or egg cell) receives only one copy of each chromosome. If homologous chromosomes failed to separate, the resulting gametes would have an abnormal number of chromosomes, a condition known as aneuploidy. This can lead to developmental problems, infertility, or spontaneous miscarriage. Therefore, the precise separation of homologous chromosomes is essential for maintaining the correct chromosome number across generations.

Stages of Meiosis I: Focusing on Homologous Chromosome Separation

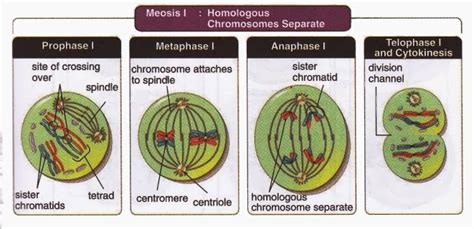

Meiosis I is comprised of several stages, each playing a vital role in the separation of homologous chromosomes. These stages are:

1. Prophase I: A Critical Stage for Homologous Chromosome Pairing and Recombination

Prophase I is the longest and most complex phase of Meiosis I. This is where the crucial events leading to homologous chromosome separation take place:

-

Pairing of Homologous Chromosomes (Synapsis): Homologous chromosomes identify and align with each other, a process known as synapsis. This alignment is remarkably precise, ensuring that the corresponding genes on each chromosome are positioned opposite each other. The paired homologous chromosomes are now referred to as a bivalent or a tetrad (because it contains four chromatids).

-

Formation of the Synaptonemal Complex: A protein structure called the synaptonemal complex forms between the homologous chromosomes, holding them together tightly. This complex plays a crucial role in facilitating the next crucial step.

-

Crossing Over (Recombination): Non-sister chromatids of homologous chromosomes exchange segments of DNA. This process, known as crossing over or recombination, creates new combinations of alleles on the chromosomes, significantly contributing to genetic variation among offspring. The points where crossing over occurs are visible as chiasmata. These chiasmata physically connect the homologous chromosomes, further ensuring their proper alignment and subsequent separation.

-

Chromosome Condensation: Throughout Prophase I, the chromosomes continue to condense, becoming shorter and thicker, making them easier to visualize and manipulate during the later stages of meiosis.

2. Metaphase I: Alignment at the Metaphase Plate

In Metaphase I, the bivalents (paired homologous chromosomes) migrate to the metaphase plate, an imaginary plane in the center of the cell. The orientation of each bivalent at the metaphase plate is random. This independent assortment of homologous chromosomes is another key mechanism contributing to genetic diversity. Each homologous chromosome can orient towards either pole of the cell independently of the other bivalents. This random alignment ensures that the daughter cells receive a unique combination of maternal and paternal chromosomes.

3. Anaphase I: The Separation of Homologous Chromosomes

Anaphase I marks the actual separation of homologous chromosomes. The kinetochore microtubules, which attach to the centromeres of each chromosome, shorten and pull the homologous chromosomes apart. Crucially, sister chromatids remain attached at their centromeres; it's the homologous chromosomes that separate. This contrasts with mitosis and Anaphase II of meiosis, where it is the sister chromatids that separate. This separation is driven by the molecular motors associated with the microtubules, resulting in a precise and controlled movement of chromosomes toward opposite poles of the cell.

4. Telophase I and Cytokinesis: Completion of Meiosis I

Telophase I sees the arrival of homologous chromosomes at opposite poles of the cell. The nuclear envelope may reform around each set of chromosomes, and the chromosomes may decondense slightly. Cytokinesis, the division of the cytoplasm, then occurs, resulting in two haploid daughter cells. These daughter cells are genetically different from each other and from the parent cell due to crossing over and independent assortment.

Meiosis II: A Mitotic-like Division

While Meiosis I is the stage where homologous chromosomes separate, Meiosis II is more similar to a mitotic division. It involves the separation of sister chromatids, ensuring that each of the four final gametes receives only one copy of each chromosome. Meiosis II does not involve further recombination or independent assortment.

Errors in Homologous Chromosome Separation: The Consequences of Nondisjunction

Errors in the separation of homologous chromosomes during Meiosis I, a process called nondisjunction, can have severe consequences. Nondisjunction occurs when homologous chromosomes fail to separate properly during Anaphase I. This results in gametes with an abnormal number of chromosomes. For example, if a pair of homologous chromosomes fails to separate, one daughter cell will receive both chromosomes (n+1), while the other will receive neither (n-1). Fertilization of these gametes by normal gametes will lead to zygotes with trisomy (three copies of a chromosome) or monosomy (one copy of a chromosome), respectively.

Down syndrome (trisomy 21) is a well-known example of a chromosomal abnormality caused by nondisjunction. Other conditions such as Turner syndrome (monosomy X) and Klinefelter syndrome (XXY) also result from nondisjunction during meiosis. These chromosomal abnormalities often lead to developmental problems, intellectual disabilities, and other health issues. The severity of the consequences of nondisjunction depends on the specific chromosome involved and the number of affected chromosomes.

Factors Affecting Homologous Chromosome Separation

Several factors influence the accurate separation of homologous chromosomes during Meiosis I. These include:

-

The Synaptonemal Complex: As mentioned earlier, this protein structure plays a critical role in holding homologous chromosomes together during Prophase I and ensuring their proper alignment. Disruptions to the formation or function of the synaptonemal complex can lead to nondisjunction.

-

Cohesin Proteins: These proteins hold sister chromatids together. The regulation of cohesin activity is crucial for the timing of both sister chromatid separation in Anaphase II and homologous chromosome separation in Anaphase I. Improper regulation can result in premature separation or failure to separate.

-

Microtubule Dynamics: The proper assembly and function of microtubules are essential for chromosome movement during Anaphase I. Errors in microtubule dynamics can lead to the mis-segregation of chromosomes.

-

Checkpoint Mechanisms: Cells have sophisticated mechanisms to monitor the fidelity of chromosome segregation. These checkpoints can detect errors such as incomplete synapsis or improper chromosome alignment and delay the progression of meiosis until the errors are corrected. Failures in these checkpoints can allow nondisjunction to occur.

-

Genetic Factors: Specific genes play critical roles in various aspects of meiosis, from the initiation of synapsis to the regulation of microtubule dynamics. Mutations in these genes can increase the risk of nondisjunction. Age is also a major factor increasing nondisjunction risks, particularly in females.

Conclusion: A Precise and Critical Process

The separation of homologous chromosomes during Meiosis I is a fundamental event in sexual reproduction, ensuring the maintenance of the correct chromosome number across generations and contributing to genetic diversity. This process is exquisitely controlled, involving intricate molecular mechanisms and precise coordination of different cellular components. Failures in this process can lead to severe consequences, highlighting the crucial importance of accurate homologous chromosome separation for both individual health and the evolutionary success of species. Further research into the underlying molecular mechanisms regulating this process continues to provide insights into human health and evolution.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Locus Of Points Equidistant From A Point And A Circle

Mar 19, 2025

-

Reproduction Is Not Essential For The Survival Of An Individual

Mar 19, 2025

-

What Is The Molecular Mass Of H3po4

Mar 19, 2025

-

Why A Cells Size Is Limited

Mar 19, 2025

-

About How Many Nephrons Are In A Kidney

Mar 19, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about In Meiosis Homologous Chromosomes Separate During . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.