How Many Nitrogen Bases Make A Codon

News Leon

Mar 23, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

How Many Nitrogenous Bases Make a Codon? Decoding the Language of Life

The fundamental unit of heredity, the gene, is a complex instruction manual written in the language of life. This language uses a four-letter alphabet – the nitrogenous bases adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), and thymine (T) (or uracil (U) in RNA) – to spell out the instructions for building and maintaining an organism. These bases are arranged into three-letter "words" called codons, which dictate the specific amino acids that form proteins. Understanding how many nitrogenous bases make up a codon is crucial to grasping the intricacies of genetic code translation and protein synthesis. This article will delve deep into the structure and function of codons, exploring their composition, decoding mechanisms, and the implications of their unique properties.

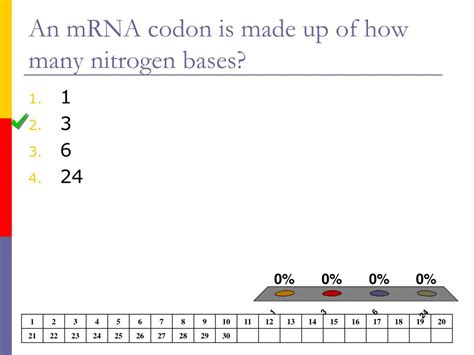

The Triplet Code: A Foundation of Molecular Biology

The answer to the question, "How many nitrogenous bases make a codon?" is a straightforward three. Each codon consists of a sequence of three consecutive nitrogenous bases on a messenger RNA (mRNA) molecule. This triplet code is a cornerstone of molecular biology, providing the framework for translating the genetic information encoded in DNA into the functional proteins that carry out life's processes.

From DNA to RNA to Protein: The Central Dogma

The flow of genetic information generally follows the central dogma of molecular biology: DNA → RNA → Protein. DNA, residing in the cell's nucleus, serves as the master blueprint. The information in DNA is transcribed into mRNA, a mobile messenger molecule that carries the genetic code to the ribosomes, the protein synthesis machinery of the cell. At the ribosomes, the mRNA codons are translated into a specific sequence of amino acids, forming a polypeptide chain that folds into a functional protein.

The Significance of Three Bases

The choice of three bases per codon is not arbitrary. A single base code (using only four bases) would only allow for four unique combinations, insufficient to encode the twenty essential amino acids required for protein synthesis. A double-base codon (four bases taken two at a time) would produce 16 (4²) combinations, still too few. However, a triplet code (four bases taken three at a time) provides 64 (4³) unique combinations, more than enough to code for all twenty amino acids and also include stop signals.

The Genetic Code: A Redundant but Unambiguous System

The genetic code is a remarkable system. While there are 64 possible codons, they code for only 20 amino acids, plus three stop codons that signal the termination of protein synthesis. This redundancy, where multiple codons can code for the same amino acid, is often referred to as degeneracy. This redundancy provides a buffer against mutations; a change in a single base might still result in the same amino acid being incorporated into the protein, preventing drastic consequences.

Degeneracy and Wobble Hypothesis

The degeneracy of the genetic code is largely explained by the wobble hypothesis. The wobble hypothesis suggests that the pairing between the third base of the codon (the 3' position) and the first base of the anticodon (on the transfer RNA, tRNA) is less stringent than the pairing between the first and second bases. This "wobble" allows a single tRNA molecule to recognize multiple codons for the same amino acid.

Start and Stop Codons: Initiating and Terminating Translation

The genetic code includes specific codons that signal the start and stop of protein synthesis. The most common start codon is AUG, which codes for methionine. This codon initiates the translation process, signaling the ribosome to begin assembling the polypeptide chain. Three codons—UAA, UAG, and UGA—function as stop codons. These codons do not code for any amino acid; instead, they trigger the termination of translation and the release of the newly synthesized protein.

The Role of Transfer RNA (tRNA): The Decoder Molecule

The process of decoding the mRNA codons and assembling the amino acid sequence involves a crucial intermediary molecule: transfer RNA (tRNA). Each tRNA molecule carries a specific amino acid and recognizes a particular codon through its anticodon, a three-base sequence complementary to the mRNA codon.

Anticodons and Codon-Anticodon Pairing

The anticodon on the tRNA molecule base-pairs with the codon on the mRNA molecule, ensuring that the correct amino acid is added to the growing polypeptide chain. This precise codon-anticodon pairing is essential for accurate protein synthesis. Mismatches can lead to the incorporation of incorrect amino acids, resulting in non-functional or even harmful proteins.

Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases: Charging the tRNAs

The process of attaching the correct amino acid to its corresponding tRNA molecule is catalyzed by a family of enzymes called aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Each enzyme is specific to a particular amino acid and its cognate tRNA. These enzymes ensure that the right amino acid is "charged" onto the tRNA, ready for incorporation into the growing polypeptide chain during translation.

Mutations and Their Impact on Codon Function

Mutations, alterations in the DNA sequence, can affect the sequence of codons in mRNA, potentially leading to changes in the amino acid sequence of the resulting protein. These changes can have varying effects, from subtle alterations in protein function to complete loss of function, or even the creation of a non-functional protein.

Point Mutations: Single-Base Changes

Point mutations involve a change in a single base in the DNA sequence. These changes can be silent (no change in amino acid sequence due to codon degeneracy), missense (a change in amino acid sequence), or nonsense (a change that introduces a premature stop codon, leading to a truncated protein).

Frameshift Mutations: Dramatic Shifts in Reading Frame

Frameshift mutations involve the insertion or deletion of one or more bases in the DNA sequence that are not multiples of three. These mutations shift the reading frame of the mRNA, altering all subsequent codons and drastically changing the amino acid sequence. Frameshift mutations often lead to non-functional proteins due to extensive alterations in their amino acid sequence.

Beyond the Basics: Exploring Advanced Concepts

The understanding of codons extends far beyond the simple three-base structure. Research continually reveals the intricate details of codon usage bias, the influence of codons on translational efficiency and accuracy, and the role of codons in gene regulation.

Codon Usage Bias: Optimizing Translation

Codon usage bias refers to the non-random preference for specific codons to encode particular amino acids in different organisms or even within different genes of the same organism. This bias can influence the efficiency and accuracy of translation. Genes that are highly expressed often utilize codons that are preferentially recognized by abundant tRNA molecules, optimizing the speed and fidelity of protein synthesis.

Codon Optimization: Engineering Protein Expression

The understanding of codon usage bias has significant implications for biotechnology and genetic engineering. Optimizing codon usage within a gene can enhance the expression of a particular protein in a specific host organism. By strategically altering codon sequences, scientists can boost protein production and improve the overall efficiency of various biotechnological applications.

The Expanding Landscape of Genetic Code Research

Research continues to unveil new facets of the genetic code. Scientists are exploring the possibility of expanding the genetic code by adding new amino acids to the repertoire, opening up new possibilities for protein engineering and drug discovery. Further investigation into the intricate details of codon usage bias and the mechanisms of translation regulation will undoubtedly continue to shape our understanding of this fundamental aspect of molecular biology. The study of the genetic code and its intricacies remains a vibrant and evolving field, constantly providing new insights into the mechanisms that drive life itself.

Conclusion: The Power of the Triplet Code

In conclusion, the answer to "How many nitrogenous bases make a codon?" is definitively three. This seemingly simple fact underlies the incredible complexity of the genetic code, a system that elegantly translates the four-letter alphabet of DNA into the vast diversity of life's proteins. The triplet code, with its inherent redundancy and precision, is a testament to the efficiency and resilience of biological systems. Ongoing research continues to unveil the profound implications of codon usage, mutations, and the ever-evolving understanding of this fundamental building block of life itself. The more we understand about codons and the genetic code, the closer we come to harnessing its power for advancements in medicine, biotechnology, and our fundamental understanding of life.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Which Of The Following Is Not A Steroid Hormone

Mar 24, 2025

-

The Layer Of Gases Surrounding Earth Is The

Mar 24, 2025

-

What Is 3 Percent Of 18

Mar 24, 2025

-

In Triangle Abc The Measure Of Angle B Is 90

Mar 24, 2025

-

Write The Iupac Name Of The Compound Shown

Mar 24, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about How Many Nitrogen Bases Make A Codon . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.