Friction Is Always Opposite To The Direction Of Motion

News Leon

Mar 15, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

Friction: Always Opposing the Motion

Friction, a force that resists motion between surfaces in contact, is a ubiquitous phenomenon shaping our everyday lives. From the simple act of walking to the complex workings of a car engine, friction plays a crucial role. Understanding friction’s fundamental nature – its inherent opposition to the direction of motion – is essential for comprehending its influence across various fields, from engineering and physics to even biology. This article delves deep into the intricacies of friction, exploring its causes, types, and practical applications, always emphasizing its defining characteristic: its opposition to motion.

Understanding the Fundamentals of Friction

At its core, friction is a consequence of the microscopic irregularities on the surfaces of contacting objects. Even surfaces appearing smooth to the naked eye exhibit intricate textures at a microscopic level. These irregularities interlock, creating resistance when one surface attempts to move across another. This interlocking, combined with other factors such as adhesion and deformation, gives rise to the frictional force.

The Microscopic Dance: Interlocking Irregularities

Imagine two seemingly smooth blocks sliding against each other. Upon closer inspection, using powerful magnification, we would see a landscape of peaks and valleys. As these surfaces attempt to slide past each other, these peaks and valleys interlock, creating a resistance to motion. The force required to overcome this interlocking is the frictional force. The greater the number and size of these irregularities, the greater the friction.

Adhesion: The Molecular Glue

Beyond simple mechanical interlocking, adhesion plays a significant role in friction. At the microscopic level, molecules on the contacting surfaces attract each other through weak intermolecular forces like van der Waals forces. These attractive forces create a bond, or "glue," between the surfaces, adding to the resistance to motion. The strength of these adhesive forces depends on the materials in contact and their surface properties.

Deformation: Yielding to Pressure

When surfaces come into contact, they often deform slightly under the applied pressure. This deformation can contribute to friction. The surfaces effectively "sink" into each other, creating additional resistance to sliding. The extent of deformation depends on the hardness and elasticity of the materials. Softer materials will deform more, resulting in higher friction.

The Two Main Types of Friction

Friction is broadly categorized into two main types: static friction and kinetic (or dynamic) friction. Both consistently oppose the direction of motion (or potential motion in the case of static friction), but they differ in their magnitude and behavior.

Static Friction: The Force Preventing Motion

Static friction is the force that prevents an object from starting to move. It acts when a force is applied to an object, but the object remains stationary. This frictional force increases with the applied force until it reaches a maximum value, at which point the object begins to move. This maximum value is called the maximum static friction. Importantly, the static frictional force always acts directly opposite to the direction of the applied force, preventing motion until this maximum is exceeded.

Example: Imagine pushing a heavy box across a floor. Initially, you apply a small force, and the box doesn't budge. The static friction is equal and opposite to your applied force. As you increase your force, the static friction also increases, keeping the box stationary. Only when your force exceeds the maximum static friction will the box begin to move.

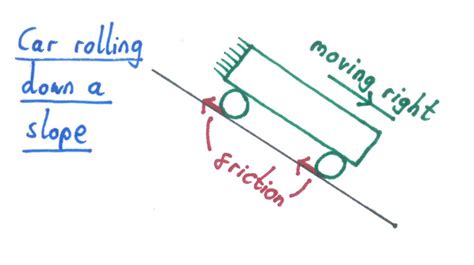

Kinetic Friction: The Force Opposing Movement

Kinetic friction, also known as dynamic friction, is the force that opposes the motion of an object already in motion. Unlike static friction, kinetic friction remains relatively constant regardless of the object's velocity (within a certain range). This constant force continuously opposes the direction of motion, slowing the object down.

Example: Once the box in the previous example starts moving, the frictional force changes to kinetic friction. This force is generally less than the maximum static friction, meaning it takes less force to keep the box moving than it did to get it started. The kinetic friction consistently acts opposite to the direction of motion, slowing the box down until it eventually comes to a stop.

Factors Influencing Friction

Several factors influence the magnitude of frictional forces:

-

Nature of the surfaces: Rougher surfaces exhibit higher friction than smoother surfaces due to increased interlocking of irregularities. The materials themselves also play a crucial role. For example, rubber on asphalt has a higher coefficient of friction than steel on ice.

-

Normal force: The normal force is the force exerted perpendicular to the surfaces in contact. The greater the normal force (e.g., heavier object), the greater the frictional force. This is because a larger normal force increases the contact area and the strength of the adhesive forces.

-

Surface area: Contrary to common misconception, the surface area in contact generally has a negligible effect on the magnitude of friction (excluding very small contact areas). While a larger surface area might seem to increase friction, the increased contact area is compensated for by a decrease in pressure per unit area, keeping the overall frictional force relatively constant.

-

Presence of lubricants: Lubricants, such as oil or grease, reduce friction by creating a thin layer between the surfaces, reducing direct contact between the irregularities and minimizing adhesive forces.

Friction: A Double-Edged Sword

Friction is a double-edged sword; it can be both beneficial and detrimental.

Beneficial Aspects of Friction

-

Walking: Friction between our shoes and the ground allows us to walk without slipping. Without friction, we would be unable to move forward.

-

Driving: Friction between the tires and the road provides traction, enabling cars to accelerate, brake, and turn.

-

Writing: Friction between the pen and paper allows us to write.

-

Machinery: While we strive to minimize friction in certain components, controlled friction is essential in many mechanical systems such as clutches, brakes, and belts.

-

Everyday tasks: Numerous everyday tasks rely on friction, from gripping objects to lighting a match.

Detrimental Aspects of Friction

-

Wear and tear: Friction causes wear and tear on mechanical parts, leading to reduced efficiency and requiring maintenance or replacement.

-

Energy loss: Friction converts kinetic energy into heat energy, resulting in energy loss. This is why engines need efficient lubrication to minimize friction and maximize efficiency.

-

Increased fuel consumption: Friction in vehicle components contributes to increased fuel consumption.

-

Slowing down of motion: Friction constantly opposes motion, inevitably slowing objects down.

Overcoming Friction: Methods and Techniques

Various methods exist to minimize or overcome friction, depending on the application:

-

Lubrication: Applying lubricants reduces friction by separating surfaces and reducing contact.

-

Streamlining: Streamlining reduces air resistance, a form of friction, making objects more aerodynamic.

-

Using rollers or bearings: Rollers and bearings reduce friction by replacing sliding contact with rolling contact.

-

Polishing surfaces: Polishing surfaces reduces surface roughness, decreasing friction.

-

Using materials with low coefficients of friction: Selecting materials with inherently low coefficients of friction can help minimize friction.

Friction in Different Contexts

Friction plays a significant role across numerous scientific and engineering disciplines:

Friction in Engineering

Engineers strive to minimize friction in many applications to increase efficiency, reduce wear, and save energy. However, they also utilize friction in other areas, such as designing brakes and clutches. Understanding friction is fundamental to designing efficient and reliable machinery.

Friction in Physics

Physics provides the fundamental understanding of the forces involved in friction. Studying friction allows us to develop models and predict the behavior of systems involving moving objects and surfaces.

Friction in Biology

Friction plays a role in biological systems, such as the movement of joints and the interaction of cells. Understanding frictional forces in biological contexts contributes to fields such as biomechanics and biomedical engineering.

Conclusion: The Ever-Present Force

Friction, always opposing the direction of motion, is a fundamental force governing the interactions between surfaces in contact. Its effects are pervasive, influencing everything from the simple act of walking to the intricate workings of advanced machinery. A deep understanding of friction's nature, types, and influencing factors is crucial across numerous fields, enabling the development of innovative solutions that either minimize or harness its power to enhance efficiency, safety, and performance. From minimizing friction to maximize efficiency in machines, to utilizing friction to create traction and stability, the mastery of this ever-present force remains a cornerstone of technological advancement and a captivating subject of scientific inquiry.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Is The Bond Order Of N2

Mar 15, 2025

-

Example Of Essay About Who Am I

Mar 15, 2025

-

The Membranes Of Cells Are Composed Primarily Of

Mar 15, 2025

-

Which Of The Following Events Does Not Occur During Prophase

Mar 15, 2025

-

Similarities Between First And Second Great Awakening

Mar 15, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Friction Is Always Opposite To The Direction Of Motion . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.