An Oscillating Block-spring System Has A Mechanical Energy

News Leon

Mar 21, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

An Oscillating Block-Spring System Has Mechanical Energy: A Deep Dive into Simple Harmonic Motion

The seemingly simple system of a block attached to a spring, oscillating back and forth, is a cornerstone of physics. Understanding its behavior reveals fundamental principles governing energy conservation and simple harmonic motion (SHM). This comprehensive exploration delves into the mechanical energy within this system, examining its various forms, the interplay between potential and kinetic energy, and the factors influencing its overall behavior.

Understanding Simple Harmonic Motion (SHM)

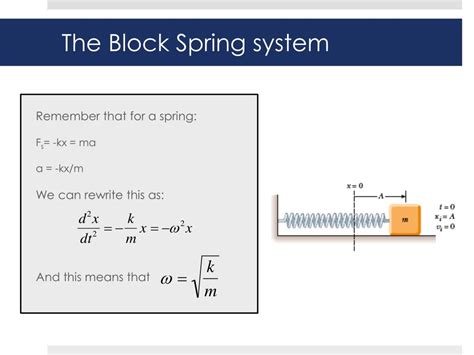

Before diving into the energy aspects, let's establish a firm understanding of SHM. A system exhibits SHM when its restoring force is directly proportional to its displacement from equilibrium and acts in the opposite direction. In our block-spring system, this restoring force is provided by Hooke's Law:

F = -kx

Where:

- F represents the restoring force exerted by the spring.

- k is the spring constant, a measure of the spring's stiffness (higher k means a stiffer spring).

- x is the displacement of the block from its equilibrium position. The negative sign indicates that the force always acts to return the block to its equilibrium.

This linear relationship between force and displacement is crucial for SHM. It leads to a sinusoidal motion, meaning the block's position, velocity, and acceleration all vary sinusoidally with time.

Key Characteristics of SHM in a Block-Spring System:

- Period (T): The time taken for one complete oscillation. It depends solely on the mass (m) of the block and the spring constant (k): T = 2π√(m/k).

- Frequency (f): The number of oscillations per unit time. It's the reciprocal of the period: f = 1/T.

- Amplitude (A): The maximum displacement of the block from its equilibrium position.

Mechanical Energy: A Constant in Ideal Systems

In an ideal block-spring system (neglecting friction and air resistance), the total mechanical energy remains constant throughout the oscillation. This energy is the sum of two forms:

- Potential Energy (PE): Stored energy due to the block's position relative to its equilibrium. For a spring, this is given by: PE = (1/2)kx²

- Kinetic Energy (KE): Energy of motion. For the block, it's given by: KE = (1/2)mv²

Where:

- v is the velocity of the block.

Therefore, the total mechanical energy (E) is:

E = PE + KE = (1/2)kx² + (1/2)mv²

This equation reveals the crucial interplay between potential and kinetic energy during the oscillation.

Energy Transformation Throughout the Oscillation:

- At Maximum Displacement (x = ±A): The block momentarily stops (v = 0), so KE = 0. All the energy is stored as potential energy: E = (1/2)kA².

- At Equilibrium Position (x = 0): The block has its maximum velocity, so PE = 0. All the energy is in the form of kinetic energy: E = (1/2)mv<sub>max</sub>².

- Between Extremes: The energy continuously transforms between potential and kinetic energy, but their sum always remains constant.

This constant energy exchange is a hallmark of SHM and a direct consequence of the conservative nature of the spring force (no energy is lost to friction or other non-conservative forces).

The Role of Spring Constant (k) and Mass (m)

The spring constant (k) and the mass (m) of the block significantly influence the system's energy and behavior:

-

Spring Constant (k): A higher spring constant signifies a stiffer spring. This results in a higher frequency of oscillation and a greater maximum potential energy for the same amplitude. The system will oscillate more rapidly.

-

Mass (m): A larger mass leads to a lower frequency of oscillation. The maximum kinetic energy will be larger for the same amplitude. The system will oscillate more slowly.

Real-World Considerations: Non-Conservative Forces

While the ideal model provides a valuable framework, real-world block-spring systems inevitably experience non-conservative forces like friction and air resistance. These forces dissipate energy from the system, gradually reducing the amplitude of the oscillations. This energy loss manifests as heat.

Damped Oscillations:

The presence of damping leads to damped oscillations. The amplitude of the oscillations gradually decreases over time until the block comes to rest at its equilibrium position. The rate of damping depends on the strength of the resistive forces.

- Weak Damping: The oscillations decay slowly over many cycles.

- Strong Damping: The oscillations decay rapidly, and the block may not even complete a full cycle before coming to rest.

Maintaining Oscillation: Driven Oscillations

To maintain oscillations in the presence of damping, we can apply an external driving force. This creates a driven oscillator. If the driving frequency is close to the system's natural frequency (determined by m and k), the amplitude of oscillation can become significantly large, a phenomenon known as resonance.

Applications of the Block-Spring System

The simple block-spring system, despite its apparent simplicity, serves as a fundamental model for various physical phenomena and has numerous practical applications:

- Modeling Molecular Vibrations: The vibrations of atoms within molecules can be approximated using a block-spring model, helping us understand molecular spectra and chemical bonding.

- Seismic Dampers in Buildings: These devices utilize the principles of damped oscillations to reduce the impact of earthquakes on buildings.

- Shock Absorbers in Vehicles: Shock absorbers use damped oscillations to absorb energy from bumps and irregularities in the road, providing a smoother ride.

- Clock Mechanisms: Early mechanical clocks utilized the regular oscillations of a pendulum (which can be modeled as a block-spring system with a specific type of restoring force) to accurately measure time.

- Mass-Spring Systems in Engineering: Many engineering applications involve mass-spring systems, such as in vibration analysis of structures and machinery.

Conclusion: A Foundation for Understanding More Complex Systems

The oscillating block-spring system, though seemingly basic, provides a crucial foundation for understanding more complex oscillatory systems. Its analysis introduces fundamental concepts like simple harmonic motion, energy conservation, and the interplay between potential and kinetic energy. The principles learned through studying this system are essential for understanding various phenomena across different fields of science and engineering, highlighting its lasting importance in physics and beyond. By grasping the energy dynamics within this simple system, we unlock a deeper comprehension of the world around us, from the microscopic vibrations of molecules to the large-scale oscillations of structures. The seemingly simple back-and-forth motion of a block on a spring holds within it a wealth of profound physical principles.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Citizens Vote To Elect Their Leaders Democracy Or Autocracy

Mar 27, 2025

-

What Layer Of Earth Is The Thinnest

Mar 27, 2025

-

Why Was The Confederation Congress Unable To Control Inflation

Mar 27, 2025

-

Difference Between Molar Mass And Molecular Mass

Mar 27, 2025

-

Blood Pressure Is Highest In The And Lowest In The

Mar 27, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about An Oscillating Block-spring System Has A Mechanical Energy . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.