What Layer Of Earth Is The Thinnest

News Leon

Mar 27, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

What Layer of Earth is the Thinnest? Exploring the Earth's Composition and Structure

The Earth, our home, is a complex and dynamic system. Understanding its structure is crucial to comprehending various geological processes, from earthquakes and volcanoes to the movement of continents and the formation of mountains. One of the most fundamental aspects of Earth science is understanding its layered composition. But which layer is the thinnest? The answer isn't as straightforward as it may seem. This article will delve deep into the Earth's layers, comparing their thicknesses and exploring the factors that contribute to their varying dimensions.

The Earth's Layered Structure: A Brief Overview

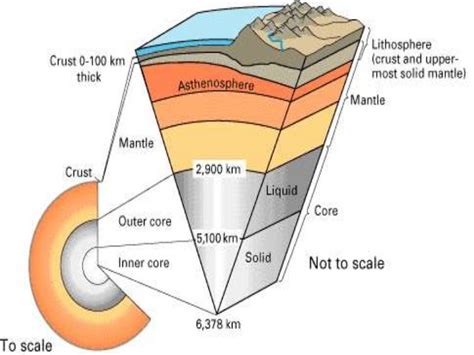

The Earth is broadly divided into four primary layers: the crust, the mantle, the outer core, and the inner core. Each layer possesses distinct physical properties, chemical compositions, and states of matter, influencing their thicknesses and behaviors.

1. The Crust: Earth's Brittle Outer Shell

The crust is the outermost solid shell of our planet. It's the thinnest of all the Earth's layers, a relatively fragile skin compared to the immense layers beneath. The crust is further divided into two distinct types:

-

Oceanic Crust: This type of crust underlies the ocean basins. It is predominantly composed of basalt, a dark-colored volcanic rock, making it denser than continental crust. Oceanic crust is significantly thinner, averaging only about 5-10 kilometers (3-6 miles) in thickness. Its thinness is attributed to the continuous process of seafloor spreading, where new crust is constantly being formed at mid-ocean ridges and older crust is subducted (pulled under) at convergent plate boundaries. This continuous cycle keeps the oceanic crust relatively young and thin.

-

Continental Crust: This type of crust forms the continents. It's primarily composed of granite, a lighter-colored igneous rock, making it less dense than oceanic crust. Continental crust is considerably thicker, averaging about 30-70 kilometers (19-43 miles) in thickness. Its thicker nature is a result of various geological processes, including the accumulation of sediments, volcanic activity, and tectonic collisions over billions of years. Some areas, like mountain ranges, can even have a crustal thickness exceeding 70 kilometers.

2. The Mantle: A Viscous Sea of Rock

Beneath the crust lies the mantle, a significantly thicker layer comprising approximately 84% of Earth's volume. It extends to a depth of about 2,900 kilometers (1,802 miles). The mantle is primarily composed of silicate rocks rich in iron and magnesium. Unlike the rigid crust, the mantle is not solid rock; instead, it exhibits ductile behavior, meaning it can deform slowly under pressure over long periods. This plasticity allows for the movement of tectonic plates, driving continental drift and other geological phenomena. The mantle is further divided into the upper mantle and the lower mantle, each possessing distinct characteristics and contributing to the overall dynamic behavior of the Earth.

3. The Outer Core: A Liquid Iron-Nickel Ocean

The outer core, extending from approximately 2,900 kilometers (1,802 miles) to 5,150 kilometers (3,200 miles) depth, is a liquid layer composed primarily of iron and nickel. The extreme temperatures and pressures in this region prevent the formation of a solid state. The movement of this liquid metallic layer is responsible for generating Earth's magnetic field through a process known as the geodynamo. This magnetic field shields our planet from harmful solar radiation.

4. The Inner Core: A Solid Iron-Nickel Sphere

At the Earth's center lies the inner core, a solid sphere with a radius of about 1,220 kilometers (760 miles). Despite the incredibly high temperatures, the immense pressure at this depth forces the iron-nickel alloy into a solid state. The inner core is believed to be slowly rotating, and its precise physical properties remain an active area of research.

Comparing the Thicknesses: The Crust as the Thinnest Layer

While the mantle constitutes the largest portion of the Earth's volume, the crust is unequivocally the thinnest layer. The contrast between the thickness of oceanic crust (5-10 km) and continental crust (30-70 km) highlights the variability within this layer. However, even at its thickest points, the continental crust remains significantly thinner than the mantle, outer core, and inner core. The relatively thin nature of the crust makes it highly susceptible to geological processes like erosion, uplift, and tectonic plate movement.

Factors Influencing Crustal Thickness

Several factors contribute to the variation in crustal thickness:

-

Plate Tectonics: The movement of tectonic plates plays a pivotal role in determining crustal thickness. At convergent plate boundaries where plates collide, crust can be thickened through compression and mountain building. Conversely, at divergent plate boundaries where plates move apart, new, thin oceanic crust is created.

-

Density Differences: The density difference between oceanic and continental crust explains the variation in their thicknesses. The denser oceanic crust is more likely to subduct under the lighter continental crust, resulting in its thinner nature.

-

Geological History: The long history of geological processes, including volcanic eruptions, sedimentation, and erosion, has shaped the thickness of the crust in different regions. Areas with a history of intense volcanic activity often possess thicker crust than regions dominated by erosion.

-

Isostatic Equilibrium: The principle of isostatic equilibrium describes the balance between the buoyant force of the crust and the gravitational forces acting upon it. Heavier crustal materials will sink deeper, causing greater thickness, while lighter materials will rise higher.

The Significance of Understanding Earth's Thin Crust

The thinness of the Earth's crust has significant implications for various geological phenomena:

-

Earthquakes: The crust's thin and brittle nature makes it prone to fracturing and faulting, leading to earthquakes.

-

Volcanism: Volcanic eruptions occur when molten rock (magma) rises from the mantle to the surface through weaknesses in the crust.

-

Mountain Building: The collision of tectonic plates causes the crust to buckle and fold, forming mountain ranges.

-

Erosion and Weathering: The relatively thin crust is susceptible to erosion and weathering processes, which constantly reshape the Earth's surface.

Conclusion: The Thin Crust and its Dynamic Role

In conclusion, the crust is the thinnest layer of the Earth, showcasing remarkable variations in thickness between oceanic and continental regions. This thinness reflects the dynamic nature of our planet, shaped by continuous geological processes driven by plate tectonics, density differences, and isostatic equilibrium. Understanding the properties and thickness variations of the Earth's layers is crucial for comprehending a multitude of geological phenomena, fostering a deeper appreciation for our planet's intricate and ever-evolving structure. Further research continues to refine our understanding of the Earth's composition and dynamics, enhancing our ability to predict and mitigate geological hazards while gaining valuable insights into the planet's history and future.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

In Which Organelles Does Cellular Respiration Take Place

Mar 30, 2025

-

Things That Are Made Out Of Metal

Mar 30, 2025

-

Where Do Transcription And Translation Occur In Prokaryotic Cells

Mar 30, 2025

-

Groups Of Cells That Are Similar In Structure And Function

Mar 30, 2025

-

Indicate Whether The Following Statements Are True Or False

Mar 30, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about What Layer Of Earth Is The Thinnest . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.