An Atomic Nucleus Has A Mass That Is

News Leon

Mar 25, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

An Atomic Nucleus Has a Mass That Is... Significantly Less Than the Sum of Its Parts? The Mystery of Mass Defect

The seemingly simple statement, "an atomic nucleus has a mass that is...", requires a surprisingly nuanced answer. While the intuitive response might be to sum the masses of its constituent protons and neutrons, the reality is far more fascinating and reveals a fundamental aspect of nuclear physics: mass defect. This article delves into the intricacies of nuclear mass, exploring the concept of mass defect, its relationship to binding energy, and the implications for nuclear stability and energy generation.

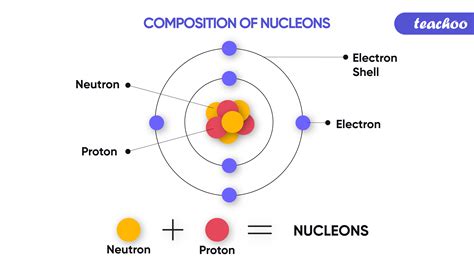

Understanding the Composition of the Atomic Nucleus

Before we dive into the intricacies of mass, let's establish a foundational understanding of the atomic nucleus. The nucleus, residing at the heart of an atom, is composed of two primary subatomic particles:

- Protons: Positively charged particles contributing to the atom's atomic number and its chemical identity.

- Neutrons: Neutral particles contributing to the atom's mass number but not its chemical properties.

The number of protons determines the element, while the combination of protons and neutrons determines the specific isotope of that element. For instance, all carbon atoms have six protons, but the common isotopes are Carbon-12 (6 protons, 6 neutrons) and Carbon-14 (6 protons, 8 neutrons).

The Astonishing Revelation of Mass Defect

Now, let's address the core question: What is the mass of an atomic nucleus? The straightforward approach would be to add the masses of individual protons and neutrons. However, this calculation consistently yields a result greater than the actual measured mass of the nucleus. This difference is known as the mass defect.

This seemingly small discrepancy is monumental in its implications. The mass defect represents the "missing" mass, which is not simply lost but is converted into a different form of energy—nuclear binding energy. This energy is the force holding the nucleus together, overcoming the electrostatic repulsion between positively charged protons. The stronger the binding energy, the more stable the nucleus.

Einstein's E=mc²: The Energy-Mass Equivalence

The relationship between mass and energy is elegantly encapsulated by Einstein's famous equation, E=mc². This equation reveals that mass (m) and energy (E) are interchangeable, with the speed of light (c) acting as the conversion factor. The mass defect, therefore, represents the energy released when the nucleus is formed from its constituent protons and neutrons. This energy is precisely the binding energy that holds the nucleus together.

This conversion of mass to energy explains why the actual mass of the nucleus is less than the sum of its parts. The energy released during nuclear formation represents the "missing" mass, according to the principles of mass-energy equivalence.

Calculating Binding Energy and Mass Defect

Let's illustrate the concept with a numerical example. Consider Helium-4 (⁴He), consisting of two protons and two neutrons. The individual masses are approximately:

- Mass of proton: 1.007276 amu (atomic mass units)

- Mass of neutron: 1.008665 amu

The expected mass of ⁴He based on the sum of its components would be: (2 * 1.007276 amu) + (2 * 1.008665 amu) = 4.031882 amu

However, the experimentally measured mass of ⁴He is approximately 4.001506 amu. The difference is the mass defect:

4.031882 amu - 4.001506 amu = 0.030376 amu

This mass defect is converted into binding energy. Using Einstein's equation (E=mc²), we can calculate this energy. We need to convert the mass defect from atomic mass units to kilograms and use the appropriate value for the speed of light (c = 3 x 10⁸ m/s). This conversion involves using the atomic mass unit-kilogram conversion factor (1 amu ≈ 1.66 x 10⁻²⁷ kg). The detailed calculation is beyond the scope of this introductory explanation but ultimately yields a substantial amount of binding energy.

Binding Energy per Nucleon: A Measure of Nuclear Stability

While the total binding energy is informative, it's more useful to consider the binding energy per nucleon. This value represents the average binding energy per proton or neutron in the nucleus. A higher binding energy per nucleon indicates a more stable nucleus. A plot of binding energy per nucleon versus mass number reveals a trend:

- Light nuclei: Have relatively low binding energy per nucleon.

- Intermediate nuclei: Exhibit a peak in binding energy per nucleon around iron (Fe). These nuclei are the most stable.

- Heavy nuclei: Show a decrease in binding energy per nucleon.

This trend explains why nuclear fission (splitting heavy nuclei) and nuclear fusion (combining light nuclei) are energy-releasing processes. In both cases, the products of the reaction have a higher binding energy per nucleon than the reactants, resulting in a net release of energy. This energy release is a direct consequence of the mass defect.

Implications of Mass Defect: Nuclear Reactions and Energy Generation

The concept of mass defect and its implications have profound consequences for our understanding of nuclear reactions and energy generation:

-

Nuclear Fission: The splitting of heavy nuclei, such as uranium, into smaller nuclei releases a substantial amount of energy because the resultant nuclei have a higher binding energy per nucleon. Nuclear power plants and nuclear weapons rely on this principle.

-

Nuclear Fusion: The combining of light nuclei, such as hydrogen isotopes (deuterium and tritium), into heavier nuclei (helium) also releases vast amounts of energy. This process powers the sun and other stars. Controlled nuclear fusion is a promising future energy source.

-

Radioactive Decay: Unstable nuclei undergo radioactive decay to achieve a more stable configuration, often emitting particles and energy in the process. The energy released is again a consequence of the difference in binding energy between the parent and daughter nuclei.

Beyond Protons and Neutrons: The Role of Other Particles

While protons and neutrons are the primary constituents of the nucleus, other subatomic particles also play a role, albeit a less dominant one. These include:

-

Gluons: Particles mediating the strong nuclear force, the force responsible for holding protons and neutrons together within the nucleus.

-

Quarks: Fundamental particles that make up protons and neutrons.

Understanding the interactions between these particles provides a deeper insight into the intricacies of nuclear structure and the origin of mass defect.

Conclusion: The Profound Significance of a "Missing" Mass

The seemingly simple question of the atomic nucleus's mass leads us to a profound understanding of the universe's fundamental laws. The mass defect, a seemingly minor discrepancy between the expected and measured mass, is a testament to the power of Einstein's E=mc² and the immense energy stored within the atomic nucleus. This energy release, a direct consequence of the mass defect, drives nuclear reactions, powers stars, and holds immense potential for future energy generation. The continued exploration of nuclear physics promises further insights into the fascinating relationship between mass, energy, and the stability of matter itself. The seemingly small "missing" mass holds the key to unlocking vast amounts of energy and understanding the very fabric of the universe.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

To Whom Did India Give The Title Mahatma

Mar 26, 2025

-

The Temperature At Which A Solid Becomes A Liquid

Mar 26, 2025

-

What Is The Smallest Biological Unit That Can Evolve

Mar 26, 2025

-

The Fibrous Connective Tissue That Wraps Muscle Is Called

Mar 26, 2025

-

An Oscillator Consists Of A Block Attached To A Spring

Mar 26, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about An Atomic Nucleus Has A Mass That Is . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.