A Translocation Is An Exchange Of Segments Between Non-homologous

News Leon

Mar 25, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

A Translocation is an Exchange of Segments Between Non-Homologous Chromosomes: A Deep Dive

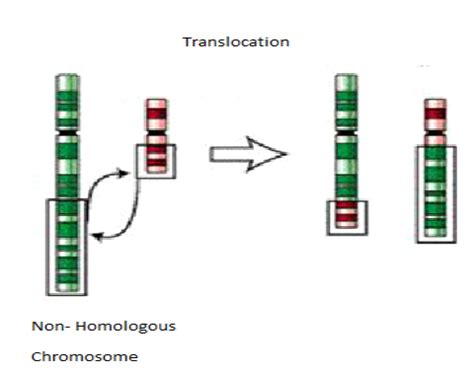

A translocation is a type of chromosomal abnormality where a segment of one chromosome breaks off and attaches to a non-homologous chromosome. This means that the exchanged segments aren't from chromosomes that normally pair up during meiosis (like homologous chromosomes). This process can have significant consequences, ranging from subtle effects to severe developmental disorders and increased cancer risk. Understanding the mechanisms, types, and consequences of translocations is crucial in genetics and medicine.

The Mechanics of Translocation: A Complex Dance of Chromosomes

The fundamental process behind a translocation involves chromosome breakage and subsequent rejoining. This isn't a random event; specific factors, both genetic and environmental, can influence the likelihood of a translocation occurring. While the exact mechanisms aren't fully elucidated for all cases, several key players are implicated:

1. DNA Double-Strand Breaks (DSBs): The Initiating Event

The most common initiating event for a translocation is a double-strand break (DSB) in the DNA. These breaks can arise from various sources, including:

- Ionizing radiation: X-rays and gamma rays can directly damage DNA, leading to DSBs.

- Certain chemicals: Some chemicals are known to be genotoxic, causing DNA damage and increasing the risk of DSBs.

- Replication errors: Mistakes during DNA replication can result in DSBs.

- Oxidative stress: Reactive oxygen species (ROS) can damage DNA, leading to DSBs.

2. DNA Repair Mechanisms: A Potential Pathway to Translocation

The cell has sophisticated mechanisms to repair DSBs. However, errors in these repair processes can lead to translocations. Two major pathways are involved:

- Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ): This pathway is a quick and dirty method of joining broken DNA ends. While efficient, it's error-prone and can result in insertions or deletions of DNA sequences, increasing the likelihood of translocations.

- Homologous recombination (HR): This pathway utilizes a homologous chromosome as a template to accurately repair the break. While highly accurate, it's slower than NHEJ and might not always be available (e.g., during certain phases of the cell cycle). Errors in HR can also contribute to translocations.

3. The Role of Chromatin Structure: A Subtle Influence

Chromatin, the complex of DNA and proteins that forms chromosomes, plays a role in the likelihood of translocations. Regions of chromatin that are loosely packed (euchromatin) might be more susceptible to DSBs and subsequent translocation events than tightly packed regions (heterochromatin). This is due to greater accessibility of loosely packed chromatin to the cellular machinery responsible for both DNA damage and repair.

Types of Translocations: A Categorization Based on Chromosome Involvement

Translocations are categorized based on the nature of the chromosome segments involved:

1. Reciprocal Translocations: A Balanced Exchange

Reciprocal translocations involve a mutual exchange of chromosome segments between two non-homologous chromosomes. This means that no genetic material is gained or lost; the total amount of DNA remains constant. While seemingly balanced, reciprocal translocations can still have phenotypic consequences due to gene disruption or altered gene expression. For example, a gene might be moved to a location where its regulation is different, leading to altered protein production.

2. Robertsonian Translocations: A Fusion of Chromosomes

Robertsonian translocations involve the fusion of two acrocentric chromosomes (chromosomes with the centromere near one end) at their centromeres. This results in a single, larger chromosome and a smaller chromosome that is often lost. This loss of genetic material is usually not severe because acrocentric chromosomes often contain repetitive DNA sequences with minimal gene content. However, this fusion can lead to monosomy or trisomy of chromosomes involved in the subsequent meiosis, leading to developmental disorders such as Down Syndrome.

Phenotypic Consequences of Translocations: A Wide Spectrum of Effects

The phenotypic consequences of translocations vary significantly, depending on several factors:

- The location of the breakpoint: If the breakpoint falls within a gene, the gene's function can be disrupted, leading to a clear phenotype. Even breakpoints outside of genes can influence gene expression by altering regulatory elements.

- The size of the translocated segment: Larger translocations are more likely to disrupt genes or regulatory sequences and hence have a more profound effect.

- The type of translocation: Reciprocal translocations, while appearing balanced, can still have significant consequences, while Robertsonian translocations can lead to aneuploidy.

- The involvement of specific chromosomes: Translocations involving specific genes or chromosome regions can lead to more severe or specific phenotypes.

Examples of Translocation-Related Disorders

-

Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia (CML): The Philadelphia chromosome, a reciprocal translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22, is a hallmark of CML. This translocation fuses the ABL1 gene (from chromosome 9) with the BCR gene (from chromosome 22), creating a fusion protein that drives uncontrolled cell growth.

-

Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL): Another example is the translocation between chromosomes 15 and 17, which fuses the PML and RARA genes, resulting in APL.

-

Down Syndrome: Robertsonian translocations involving chromosome 21 can lead to familial Down Syndrome, where a parent carries a translocation chromosome involving chromosome 21 and subsequently passes on an extra copy of chromosome 21 to their offspring.

-

Other Disorders: Many other cancers and developmental disorders are associated with translocations, highlighting the wide-ranging impact of these chromosomal abnormalities.

Detecting Translocations: Cytogenetic and Molecular Techniques

Several techniques are employed to detect translocations:

1. Karyotyping: A Classical Cytogenetic Approach

Karyotyping involves visualizing chromosomes under a microscope to identify structural abnormalities, such as translocations. This method can reveal large-scale translocations but might miss smaller ones.

2. Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH): A Targeted Approach

FISH uses fluorescently labeled DNA probes to detect specific DNA sequences on chromosomes. This technique allows for the precise localization of translocated segments and is particularly useful in identifying specific translocations, like the Philadelphia chromosome in CML.

3. Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization (aCGH): A High-Resolution Technique

aCGH compares the DNA of a patient with a reference DNA sample to detect gains or losses of genetic material. This method can detect smaller translocations that might be missed by karyotyping.

4. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): A Comprehensive Approach

NGS allows for the sequencing of entire genomes or specific regions of interest, enabling the identification of translocations with high accuracy and resolution. This approach is becoming increasingly important for detecting complex or cryptic translocations.

The Significance of Translocations in Cancer and Disease

Translocations play a critical role in the development of several cancers and other genetic disorders. The disruption of genes involved in cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, or DNA repair can lead to uncontrolled cell growth, contributing to tumor formation. Furthermore, the altered gene expression patterns resulting from translocations can contribute to various phenotypic effects. The study of translocations therefore offers invaluable insights into cancer mechanisms, disease pathogenesis, and development of novel therapeutic strategies.

Conclusion: A Complex Phenomenon with Far-Reaching Implications

Translocations represent a complex class of chromosomal abnormalities that underscore the intricate nature of genome stability and the consequences of its disruption. Understanding the mechanisms, types, and phenotypic effects of translocations is crucial for diagnosing and managing various genetic disorders and cancers. Advanced techniques like NGS continue to improve our ability to detect and characterize these events, paving the way for better diagnosis, prognosis, and ultimately, personalized treatments. The field continues to evolve, providing deeper insights into the intricate relationship between genomic instability and disease. Further research will undoubtedly unravel more secrets of these fascinating chromosomal rearrangements, further advancing our understanding of human health and disease.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

A Rotating Fan Completes 1200 Revolutions

Mar 28, 2025

-

1 Meter Equals How Many Millimeters

Mar 28, 2025

-

In The System Of Mass Production Unskilled Workers

Mar 28, 2025

-

What Is The Ph Of The Neutral Solution

Mar 28, 2025

-

Respiratory Control Centers Are Located In The

Mar 28, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about A Translocation Is An Exchange Of Segments Between Non-homologous . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.