What Is The Correct Order For The Scientific Method

News Leon

Mar 18, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

- What Is The Correct Order For The Scientific Method

- Table of Contents

- What is the Correct Order for the Scientific Method? A Deep Dive

- The Core Components: More Than Just a Linear Sequence

- 1. Observation: The Spark of Inquiry

- 2. Question: Formulating a Testable Inquiry

- 3. Hypothesis: A Testable Prediction

- 4. Experimentation: Rigorous Testing

- 5. Data Analysis: Interpreting the Results

- 6. Conclusion: Drawing Inferences and Revising the Hypothesis

- Debunking Misconceptions: The Scientific Method Isn't Always Linear

- Examples of Non-Linearity:

- The Importance of Peer Review and Replication

- Beyond the Basics: Variations and Extensions

- Conclusion: Embracing the Cyclical Nature of Discovery

- Latest Posts

- Latest Posts

- Related Post

What is the Correct Order for the Scientific Method? A Deep Dive

The scientific method is a cornerstone of scientific inquiry, a systematic approach to understanding the natural world. While often simplified in introductory science classes, the reality is far more nuanced and iterative. There's no single, rigid "correct" order, but rather a flexible framework that adapts to the specific research question and context. This article will explore the core components of the scientific method, discuss the common misconceptions surrounding its linear representation, and delve into the iterative and cyclical nature of scientific discovery.

The Core Components: More Than Just a Linear Sequence

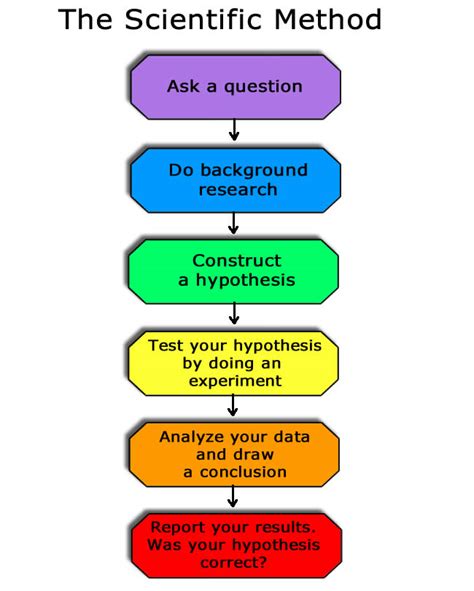

The popularized version of the scientific method often presents it as a linear progression: Observation, Question, Hypothesis, Experiment, Analysis, Conclusion. While this provides a useful starting point, it oversimplifies the complex and often messy process of scientific investigation. A more accurate representation acknowledges the iterative and cyclical nature of the process, recognizing that scientists frequently revisit earlier stages based on new findings or unexpected results.

1. Observation: The Spark of Inquiry

Scientific inquiry often begins with observation, a careful and meticulous examination of the world around us. This might involve observing natural phenomena, analyzing existing data, or noticing inconsistencies in current theories. Crucially, this observation isn't just passive; it involves actively seeking patterns, anomalies, and intriguing questions that warrant further investigation. The sharpness and depth of observation directly influences the quality and relevance of the subsequent steps.

Examples:

- Observing a higher rate of plant growth near a particular stream.

- Noticing a correlation between increased screen time and sleep disturbances in children.

- Recognizing a discrepancy between theoretical predictions and experimental results in a physics experiment.

2. Question: Formulating a Testable Inquiry

A compelling question arises from the observation, focusing the research direction. This question needs to be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART), setting the stage for a focused and fruitful investigation. Vague or overly broad questions hinder progress and make effective experimentation difficult.

Examples:

- Does the proximity to the stream contribute to the observed increased plant growth?

- Is there a causal relationship between increased screen time and reduced sleep quality in children?

- How can the discrepancy between theoretical and experimental results be resolved in this physics experiment?

3. Hypothesis: A Testable Prediction

A hypothesis is a tentative explanation or prediction that attempts to answer the research question. It must be testable, meaning that it can be subjected to experimental verification or falsification. A well-crafted hypothesis often takes the form of an "if-then" statement, clearly outlining the expected relationship between variables. Importantly, a hypothesis is not a mere guess; it is based on existing knowledge, observations, and logical reasoning.

Examples:

- If plants are exposed to water from the stream, then they will exhibit higher growth rates compared to plants exposed to other water sources.

- If children reduce their screen time, then their sleep quality will improve.

- If we adjust the experimental setup in this manner, then the discrepancy between theoretical and experimental results will be eliminated.

4. Experimentation: Rigorous Testing

The experiment is the crucial phase where the hypothesis is tested. This involves designing a controlled experiment, manipulating independent variables while carefully measuring the dependent variables. The design should minimize bias and confounding variables to ensure accurate and reliable results. Replicating the experiment multiple times enhances the reliability and validity of the findings.

Key Considerations in Experimentation:

- Control Group: A group not exposed to the manipulated variable serves as a baseline for comparison.

- Randomization: Participants or experimental units are randomly assigned to different groups to minimize bias.

- Blinding: Researchers or participants may be unaware of the treatment group assignment to further reduce bias.

- Data Collection: Accurate and precise data collection methods are crucial for valid conclusions.

5. Data Analysis: Interpreting the Results

After the experiment, the collected data needs to be analyzed. This often involves statistical methods to determine whether the results are significant and support or refute the hypothesis. Data visualization techniques, such as graphs and charts, are crucial for communicating the results effectively. This stage also involves identifying potential sources of error and limitations of the study.

6. Conclusion: Drawing Inferences and Revising the Hypothesis

Based on the data analysis, a conclusion is drawn regarding whether the hypothesis is supported or refuted. This conclusion isn't necessarily a final answer; it may lead to further questions and refinements of the hypothesis. The scientific method is a cyclical process, and the conclusion often informs the design of future experiments or modifications to existing theories.

The Iterative Nature of the Scientific Method: The conclusion may lead back to any previous step: a revised hypothesis, a modified experimental design, or even a re-evaluation of the initial observation. The process is not linear but rather a dynamic interplay between observation, hypothesis testing, and refinement of understanding.

Debunking Misconceptions: The Scientific Method Isn't Always Linear

A common misconception is the perception of the scientific method as a strict, linear sequence. In reality, it's far more flexible and iterative. Scientists might revisit earlier stages based on new data, unexpected results, or refined understanding. For example, an experiment might reveal unexpected results leading to a revised hypothesis, a new experimental design, or even a completely new research question.

Examples of Non-Linearity:

- Unexpected Results: An experiment might yield results contrary to the initial hypothesis. This necessitates revisiting the hypothesis, experimental design, or even the initial observation.

- New Technology: The development of new technologies can open up new avenues of investigation, requiring a re-evaluation of existing hypotheses and experimental methods.

- Interdisciplinary Approaches: Research often involves collaborations across multiple disciplines, influencing the research process and making it less linear.

The Importance of Peer Review and Replication

The scientific method is not solely an individual endeavor; it relies heavily on peer review and replication. Peer review involves subjecting research findings to critical scrutiny by other experts in the field. This helps identify potential flaws, biases, and limitations in the research process, ensuring the integrity and reliability of scientific knowledge. Replication, the repetition of an experiment by independent researchers, further validates the findings and strengthens the confidence in the results.

Beyond the Basics: Variations and Extensions

The basic framework described above represents a simplified model. The specific steps and their order can vary significantly depending on the research question and field of study. For instance, some research might rely heavily on observational studies rather than controlled experiments. Others might involve complex modeling and simulation techniques. The key is that the underlying principles of systematic investigation, critical evaluation, and iterative refinement remain central to all scientific inquiry.

Conclusion: Embracing the Cyclical Nature of Discovery

The scientific method is not a rigid recipe but a flexible framework for understanding the natural world. While a simplified linear representation can be helpful as an introduction, it's crucial to appreciate the iterative and cyclical nature of the process. Scientists frequently revisit earlier stages based on new data, unexpected results, or refined understanding. By embracing this dynamic and flexible approach, scientists can continue to unravel the mysteries of the universe and advance our understanding of the world around us. The true power of the scientific method lies in its ability to adapt, evolve, and constantly refine our knowledge through rigorous investigation and critical evaluation. It is a continuous process of questioning, testing, refining, and ultimately, expanding our knowledge base. The pursuit of knowledge is, itself, a continuous cycle, mirroring the process by which we arrive at that understanding.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

How Many Chambers Are In A Fish Heart

Mar 18, 2025

-

In Which Of These Can Convection Not Occur

Mar 18, 2025

-

What Is Blending Theory Of Inheritance

Mar 18, 2025

-

Does Bacteria Contain Dna Or Rna

Mar 18, 2025

-

What Is 13 Out Of 20 As A Percentage

Mar 18, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about What Is The Correct Order For The Scientific Method . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.