The Figure Shows Particles 1 And 2

News Leon

Mar 16, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

Decoding the Dynamics: A Deep Dive into the Interactions of Particles 1 and 2

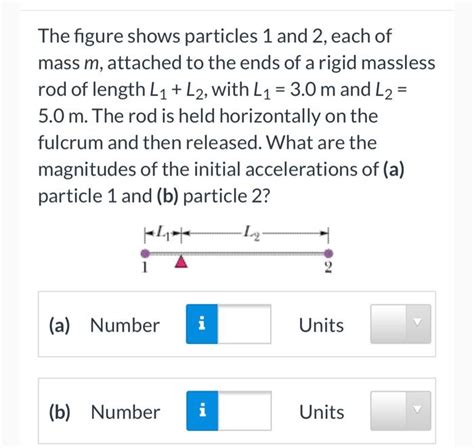

The simple statement, "The figure shows particles 1 and 2," opens a vast landscape of possibilities. Without the figure itself, we must rely on general principles of physics and mathematics to explore the potential interactions and dynamics these particles might exhibit. This exploration will delve into various scenarios, considering different properties like mass, charge, spin, and the forces governing their behavior. We'll touch upon classical mechanics, quantum mechanics, and even some relativistic considerations, demonstrating the richness and complexity inherent in even the simplest systems.

Classical Mechanics: A Newtonian Perspective

If we assume a classical mechanics framework, particles 1 and 2 can be treated as point masses interacting through forces. The nature of these forces dictates their motion. Several key interactions are worth exploring:

Gravitational Interaction:

If the particles possess mass (m₁ and m₂), they will experience a mutual gravitational attraction. Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation describes this force:

F = G * (m₁ * m₂) / r²

where:

- F is the gravitational force

- G is the gravitational constant

- m₁ and m₂ are the masses of the particles

- r is the distance between the particles

This force is always attractive, and its magnitude decreases rapidly with increasing distance. The motion of the particles under this force can be complex, ranging from simple elliptical orbits (for two-body systems) to chaotic trajectories in more complex scenarios involving multiple particles.

Electrostatic Interaction:

If the particles carry electric charges (q₁ and q₂), they will interact through the Coulomb force:

F = k * (q₁ * q₂) / r²

where:

- F is the electrostatic force

- k is Coulomb's constant

- q₁ and q₂ are the charges of the particles

- r is the distance between the particles

This force can be attractive (opposite charges) or repulsive (like charges), and, like gravity, its strength diminishes with distance. The resulting motion can vary widely depending on the charges and initial conditions. For example, two particles with like charges will repel each other, while those with opposite charges will attract and potentially form a bound state.

Other Classical Forces:

Beyond gravity and electromagnetism, other classical forces could be at play, depending on the context. These might include:

- Strong Nuclear Force: This force is responsible for binding protons and neutrons within the nucleus of an atom. Its short range and immense strength are essential for the stability of matter.

- Weak Nuclear Force: This force governs radioactive decay and certain particle interactions. Its effects are much weaker than the strong force but are crucial in nuclear processes.

- Elastic Forces: If the particles are connected by a spring or represent parts of an elastic material, elastic forces will influence their motion. Hooke's Law describes this force: F = -k * x, where x is the displacement from equilibrium and k is the spring constant.

Quantum Mechanics: A Probabilistic Realm

The classical approach breaks down at the atomic and subatomic levels. In the realm of quantum mechanics, the behavior of particles 1 and 2 becomes significantly more complex and probabilistic.

Wave-Particle Duality:

Quantum mechanics dictates that particles exhibit both wave-like and particle-like properties. Their behavior is governed by wave functions, which describe the probability of finding the particles at a particular location. The uncertainty principle introduces inherent limitations on the precision with which we can simultaneously know a particle's position and momentum.

Quantum Superposition:

Particles can exist in a superposition of states, meaning they can be in multiple states simultaneously until a measurement is made. This means the particles' properties (like position or momentum) are not definitively determined until observed.

Quantum Entanglement:

If particles 1 and 2 are entangled, their fates become intertwined regardless of the distance separating them. Measuring a property of one particle instantly influences the state of the other, even if they are light-years apart. This phenomenon has profound implications for quantum computing and communication.

Specific Particle Interactions: Examples

Let's explore some specific scenarios to illustrate the diverse interactions possible:

Scenario 1: Two Electrons

Two electrons, possessing identical negative charges, will repel each other via the Coulomb force. Their quantum mechanical wave functions will overlap, leading to Pauli exclusion principle effects, preventing them from occupying the same quantum state.

Scenario 2: A Proton and an Electron

A proton (positively charged) and an electron (negatively charged) will attract each other, forming a hydrogen atom. The quantum mechanical description involves solving the Schrödinger equation to determine the probability distribution of the electron around the proton. This leads to distinct energy levels and orbitals for the electron.

Scenario 3: Two Neutrons

Neutrons are neutral particles, but they interact through the strong nuclear force at short ranges. This force is crucial for holding neutrons together within atomic nuclei.

Scenario 4: A Photon and an Electron

A photon (a particle of light) can interact with an electron through Compton scattering or photoelectric effect. In Compton scattering, the photon transfers some of its energy to the electron, causing a change in the photon's wavelength. In the photoelectric effect, the photon's energy is completely absorbed by the electron, leading to its ejection from an atom.

Relativistic Effects: High-Speed Considerations

If the particles are moving at speeds approaching the speed of light, relativistic effects become significant. Einstein's theory of special relativity introduces corrections to Newtonian mechanics:

- Mass-Energy Equivalence (E=mc²): The mass of a particle increases with its velocity, affecting its momentum and kinetic energy.

- Time Dilation and Length Contraction: Time intervals and lengths appear different to observers in different inertial frames of reference.

These relativistic corrections become crucial for high-energy particle physics experiments, where particles are accelerated to near light speed.

Conclusion: The Unfolding Story of Particles 1 and 2

The simple image of "particles 1 and 2" hides a universe of complexity. Their interactions depend heavily on their intrinsic properties and the forces governing their behavior. Whether we use a classical, quantum, or relativistic approach, understanding these interactions is fundamental to our comprehension of the physical world. Further information regarding the properties of particles 1 and 2, such as their mass, charge, and initial conditions, would allow for a more precise and quantitative analysis of their dynamics. This exploration serves as a reminder of the profound depth and endless fascination inherent in the study of physics. Further research into specific particle types and their interactions would only enhance our understanding of the universe at its most fundamental level. The potential for further exploration within this field is vast and continues to drive advancements in scientific knowledge.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Is A Webcam An Input Or Output Device

Mar 17, 2025

-

Word For A Person Who Uses Big Words

Mar 17, 2025

-

What Is 375 As A Percentage

Mar 17, 2025

-

Which Is The Correct Order Of The Scientific Method

Mar 17, 2025

-

How Long Is A Thousand Days

Mar 17, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about The Figure Shows Particles 1 And 2 . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.