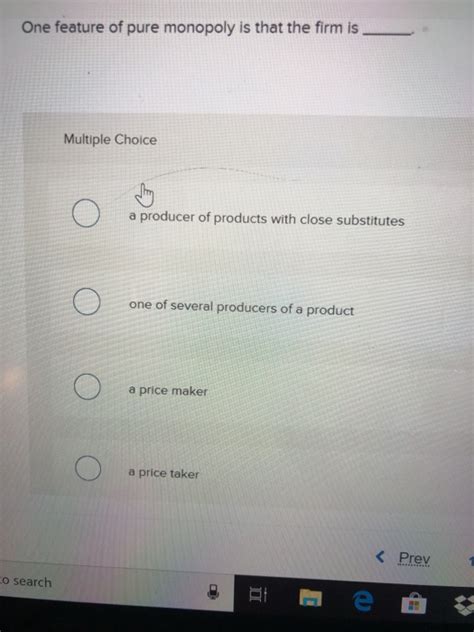

One Feature Of Pure Monopoly Is That The Firm Is

News Leon

Apr 06, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

One Feature of Pure Monopoly is That the Firm is a Price Maker, Not a Price Taker

A pure monopoly, in its strictest economic definition, describes a market structure where a single firm controls the entire supply of a particular good or service. This stark contrast to competitive markets, where numerous firms vie for consumer attention, imbues the monopolist with unique powers, particularly regarding price setting. A crucial characteristic of a pure monopoly is that the firm is a price maker, not a price taker. This article will delve deep into this defining feature, exploring its implications for consumers, producers, and the overall economy. We'll examine the mechanisms by which monopolies set prices, the factors that influence those decisions, and the potential consequences both positive and negative.

The Price-Maker Power: A Monopoly's Defining Characteristic

In a perfectly competitive market, individual firms are price takers. They have no control over the market price; they simply accept the prevailing price determined by the interaction of overall market supply and demand. If a firm attempts to charge a higher price, consumers will simply switch to competitors offering the same good or service at the lower, market price. The firm, therefore, has no incentive to deviate from the established price.

A pure monopolist, however, enjoys a completely different reality. Because there are no close substitutes for the good or service it offers, the monopolist faces a downward-sloping demand curve. This signifies that to sell more units, the monopolist must lower its price. This is in stark contrast to the perfectly elastic (horizontal) demand curve faced by firms in perfectly competitive markets. This downward-sloping demand curve gives the monopolist the power to influence the market price, making it a price maker.

Mechanisms of Price Setting in a Monopoly

Several factors influence how a monopolist determines its price. There's no single formula; rather, the monopolist aims to maximize its profits by strategically choosing both the quantity of goods/services to produce and the corresponding price. These strategies often involve considering:

-

Demand Elasticity: The monopolist must understand how sensitive consumer demand is to price changes. If demand is inelastic (consumers are relatively insensitive to price changes), the monopolist can potentially raise prices without significantly reducing sales volume. Conversely, if demand is elastic (consumers are highly sensitive to price changes), a price increase could lead to a substantial drop in sales.

-

Cost Structure: The monopolist's production costs play a significant role in determining the optimal price. The firm must consider its fixed costs (e.g., rent, equipment) and variable costs (e.g., raw materials, labor) to ascertain the profit-maximizing output level and price.

-

Market Conditions: External factors such as economic downturns, shifts in consumer preferences, or technological advancements can all influence the monopolist's pricing decisions. A recession, for instance, might necessitate a price reduction to maintain sales volume.

-

Government Regulation: In many cases, governments intervene in monopolies to protect consumers from exploitative pricing practices. Regulations can impose price ceilings, preventing the monopolist from charging excessively high prices.

-

Potential Competition: Even in a pure monopoly, the threat of potential entrants can influence pricing strategies. A monopolist might choose to set a lower price to deter new firms from entering the market.

The Profit-Maximizing Output and Price

A crucial concept in understanding monopoly pricing is the point of profit maximization. Monopolists generally aim to produce the quantity of output where marginal revenue (the additional revenue from selling one more unit) equals marginal cost (the additional cost of producing one more unit). This point signifies that producing one more unit adds less to revenue than it does to cost, making it inefficient.

Graphical Representation

The profit-maximizing price and quantity can be visualized graphically. The downward-sloping demand curve represents the consumer's willingness to pay for the monopolist's product. The marginal revenue curve lies below the demand curve, reflecting the fact that the monopolist must lower its price to sell additional units. The marginal cost curve, typically U-shaped, represents the additional cost of producing each unit. The intersection of the marginal revenue and marginal cost curves identifies the profit-maximizing output level. This quantity is then projected up to the demand curve to determine the corresponding price the monopolist will charge.

It's important to note that a monopolist's profit is represented by the area between the demand curve, the marginal cost curve, and the profit-maximizing quantity. This area will generally be larger than in a competitive market due to the absence of competitive pressure.

Consequences of Monopoly Pricing: A Double-Edged Sword

The price-making power of a monopoly yields multifaceted consequences, some beneficial and others detrimental.

Potential Benefits:

- Economies of Scale: Monopolies, due to their large size, may be able to achieve economies of scale, reducing average production costs. This can lead to lower prices for consumers in some instances, particularly if the monopolist passes on some of the cost savings.

- Innovation: The substantial profits generated by a monopoly can provide resources for research and development, potentially leading to technological advancements and the introduction of new and improved products. However, this isn't guaranteed and often depends on competitive pressures or regulatory frameworks.

- Infrastructure Investment: In certain sectors, such as utilities (electricity, water), a monopoly might be necessary to facilitate large-scale infrastructure investments that a competitive market might struggle to achieve.

Potential Drawbacks:

- Higher Prices and Reduced Consumer Surplus: The most significant drawback is the potential for higher prices and reduced output compared to a competitive market. This leads to a reduction in consumer surplus (the difference between what consumers are willing to pay and what they actually pay), transferring wealth from consumers to the monopolist.

- Reduced Output and Allocative Inefficiency: Monopolies often produce less output than a competitive market would, resulting in allocative inefficiency. This means that resources are not allocated optimally to satisfy consumer demand.

- X-Inefficiency: The absence of competition can lead to x-inefficiency, a situation where the monopolist operates at higher costs than necessary. Without competitive pressure to improve efficiency, the firm may become complacent and less innovative.

- Rent-Seeking Behavior: Monopolists may engage in rent-seeking behavior, lobbying the government for favorable regulations or policies that protect their market position. This diverts resources away from productive activities.

- Lack of Choice for Consumers: Consumers have limited or no choice in the case of a pure monopoly, restricting their ability to find the product or service that best suits their needs and preferences.

Government Regulation of Monopolies

Recognizing the potential harms of monopolies, governments often intervene through various regulatory measures:

- Antitrust Laws: These laws are designed to prevent the formation of monopolies and to break up existing ones that engage in anti-competitive practices.

- Price Controls: Governments can set price ceilings to prevent monopolists from charging excessively high prices.

- Regulation of Entry and Exit: Regulations may control the entry of new firms into the market or the exit of existing ones, ensuring a certain level of competition.

- Nationalization: In some cases, governments nationalize monopolies, bringing them under public ownership and control.

Conclusion: The Complex Reality of Monopoly Pricing

The statement that "one feature of pure monopoly is that the firm is a price maker, not a price taker" encapsulates a fundamental truth about this market structure. The price-making ability of a monopolist, however, is not inherently good or bad; its consequences are complex and depend on a multitude of factors. While monopolies may offer some benefits through economies of scale and innovation, the potential for higher prices, reduced output, and allocative inefficiency necessitates careful consideration and often necessitates government intervention to mitigate the negative impacts and foster a balance between economic efficiency and consumer welfare. The ongoing debate over the optimal level and form of regulation underscores the enduring complexity of managing monopoly power within a market economy. The crucial aspect to consider is not solely the price-making ability itself, but the effects that this power has on both the overall market and individual consumers. This necessitates constant monitoring and adaptation of regulatory frameworks to address the evolving challenges presented by monopolies in the modern economy.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Largest Organ In The Lymphatic System

Apr 08, 2025

-

What Is The Substrate Of The Enzyme Amylase

Apr 08, 2025

-

Router Operates In Which Layer Of Osi Model

Apr 08, 2025

-

What Is The Largest Organelle In A Cell

Apr 08, 2025

-

Is Osmotic Pressure A Colligative Property

Apr 08, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about One Feature Of Pure Monopoly Is That The Firm Is . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.