In The Figure You Throw A Ball Toward A Wall

News Leon

Mar 20, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

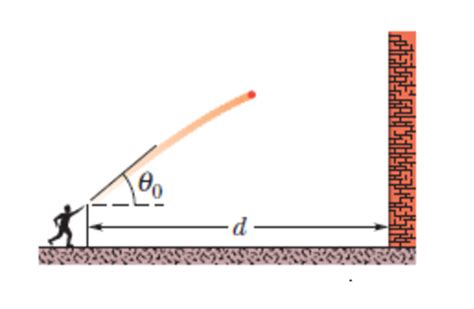

In the Figure You Throw a Ball Toward a Wall: Exploring the Physics of Projectile Motion

Throwing a ball towards a wall seems simple, a commonplace action we perform without a second thought. However, this seemingly mundane act encapsulates a rich tapestry of physics principles, specifically those governing projectile motion. Understanding this motion is crucial not only for appreciating the everyday world around us but also for various applications in sports, engineering, and beyond. This article delves into the detailed physics behind this simple act, exploring the key concepts involved and providing practical examples.

Understanding Projectile Motion

Projectile motion is defined as the motion of an object thrown or projected into the air, subject only to the acceleration due to gravity. Ignoring air resistance (a simplification we'll initially make for clarity), the object follows a parabolic trajectory. This parabolic path is a consequence of the object's horizontal velocity remaining constant while its vertical velocity changes under the influence of gravity.

Key Factors Influencing Projectile Motion

Several factors influence the trajectory of a projectile:

-

Initial Velocity: The speed and angle at which the ball is thrown significantly impact its range and maximum height. A higher initial velocity generally leads to a greater range and height. The optimal angle for maximum range is 45 degrees, assuming a flat surface and neglecting air resistance.

-

Angle of Projection: As mentioned, the angle at which the ball is thrown directly affects its path. Steeper angles lead to a greater height but shorter range, while shallower angles result in a longer range but lower maximum height.

-

Gravity: The acceleration due to gravity (approximately 9.8 m/s² on Earth) constantly pulls the ball downwards, causing its vertical velocity to change. This is the primary force shaping the parabolic trajectory.

-

Air Resistance: While we initially neglect it, air resistance (drag) is a significant factor in real-world scenarios. It opposes the motion of the ball, reducing its velocity and altering its trajectory. The effect of air resistance is dependent on factors such as the ball's shape, size, and surface texture, as well as the density of the air.

Decomposing the Motion: Horizontal and Vertical Components

To effectively analyze projectile motion, we break it down into two independent components: horizontal and vertical.

Horizontal Component

The horizontal component of the motion is characterized by constant velocity. In the absence of air resistance, there is no horizontal force acting on the ball, so its horizontal speed remains unchanged throughout its flight. We can calculate the horizontal distance (range) covered by the ball using the formula:

Range = Initial Horizontal Velocity × Time of Flight

The time of flight is determined by the vertical component of the motion.

Vertical Component

The vertical component of the motion is governed by gravity. The ball experiences a constant downward acceleration due to gravity. Its vertical velocity changes continuously, initially upwards, then decreasing to zero at the highest point of its trajectory, and finally increasing downwards until it hits the wall (or the ground).

We can use the following kinematic equations to analyze the vertical motion:

- Final Vertical Velocity = Initial Vertical Velocity - (Gravity × Time)

- Vertical Displacement = (Initial Vertical Velocity × Time) - (0.5 × Gravity × Time²)

- (Final Vertical Velocity)² = (Initial Vertical Velocity)² - (2 × Gravity × Vertical Displacement)

The Ball's Interaction with the Wall: Impulse and Rebound

When the ball strikes the wall, several things happen:

-

Impulse: The wall exerts a force on the ball over a short period, causing a change in the ball's momentum. This change in momentum is known as impulse. The impulse is equal to the average force multiplied by the time of impact.

-

Rebound: Depending on the elasticity of the collision, the ball rebounds with a certain velocity. A perfectly elastic collision would conserve kinetic energy, resulting in the ball rebounding with the same speed as it impacted the wall (though in the opposite direction). However, real-world collisions are rarely perfectly elastic; some energy is lost as heat and sound, leading to a less energetic rebound.

-

Coefficient of Restitution: This value (between 0 and 1) describes the elasticity of the collision. A coefficient of restitution of 1 indicates a perfectly elastic collision, while a coefficient of 0 means no rebound at all. The actual rebound speed can be calculated using the coefficient of restitution and the impact speed.

-

Angle of Rebound: The angle at which the ball rebounds is generally related to the angle of incidence (the angle at which it hit the wall), though surface irregularities and other factors can affect this. A perfectly smooth, flat wall would ideally produce an equal angle of incidence and reflection.

Factors Affecting Rebound: Material Properties and Surface Conditions

The material properties of both the ball and the wall significantly influence the rebound.

-

Ball Material: A harder, more elastic ball, such as one made of rubber, will generally rebound higher than a softer ball made of clay or similar materials.

-

Wall Material: A hard, smooth wall, such as one made of concrete, will result in a more elastic collision and a higher rebound than a softer, more porous wall.

-

Surface Roughness: A rough surface will cause more energy to be lost during the collision, leading to a lower rebound. A smooth surface minimizes energy loss and maximizes the rebound.

-

Spin: If the ball is spinning, this can affect the rebound angle and velocity due to the interaction of friction between the ball and the wall.

Applying the Physics: Real-World Examples and Applications

Understanding projectile motion and its interaction with surfaces has numerous real-world applications:

-

Sports: Baseball, basketball, tennis, golf, and many other sports rely heavily on principles of projectile motion. Athletes instinctively understand these principles to achieve optimal performance, though their knowledge may not be explicitly articulated in scientific terms.

-

Engineering: Projectile motion principles are crucial in designing and launching rockets, missiles, and other projectiles. Accurate calculations of trajectory and impact are essential for their successful operation.

-

Military Applications: The trajectory of artillery shells, bullets, and other projectiles is a critical factor in military applications. Understanding the effects of gravity, air resistance, and other factors is necessary to accurately target objectives.

-

Architecture and Construction: Considering the trajectory of falling objects is important in structural design to ensure safety and prevent accidents. For example, the design of building facades and protective measures against falling debris often involves calculations related to projectile motion.

Advanced Considerations: Air Resistance and Other Factors

Our analysis so far has simplified things by neglecting air resistance. However, in many real-world situations, air resistance significantly alters the trajectory and motion of the ball.

-

Drag Force: The drag force is a force that opposes the motion of the ball through the air. It depends on the speed of the ball, the density of the air, the surface area of the ball, and a drag coefficient that reflects the ball's shape and surface roughness.

-

Magnus Effect: If the ball is spinning, the Magnus effect can further modify its trajectory. The spinning ball creates a pressure difference on either side, leading to a sideways force. This is particularly evident in sports like baseball and soccer.

-

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD): For complex situations involving air resistance and spin, computational fluid dynamics simulations can provide accurate predictions of the ball's trajectory.

Conclusion

Throwing a ball towards a wall, while appearing simple, involves a sophisticated interplay of physics principles. Understanding projectile motion, including the horizontal and vertical components, the interaction with the wall, and the influence of factors like air resistance and spin, provides a deeper appreciation for the mechanics of everyday activities and has far-reaching implications across numerous fields. From sports to engineering to military applications, mastery of these principles remains essential for optimization, accuracy, and safety. By breaking down the motion into its constituent parts and considering the nuances involved, we can gain a more complete and accurate understanding of this fundamental aspect of classical mechanics.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Would Be The Best Title For This Map

Mar 20, 2025

-

Which Cycle Produces The Greater Amount Of Atp

Mar 20, 2025

-

A Monopolist Is Able To Maximize Its Profits By

Mar 20, 2025

-

An Informal Communications Network Is Known As A

Mar 20, 2025

-

What Is The Molar Mass Of Gold

Mar 20, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about In The Figure You Throw A Ball Toward A Wall . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.