How To Derive Moment Of Inertia

News Leon

Mar 21, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

How to Derive Moment of Inertia: A Comprehensive Guide

Moment of inertia, a crucial concept in physics and engineering, quantifies an object's resistance to changes in its rotation. Understanding how to derive moment of inertia is essential for analyzing rotational motion, calculating angular momentum, and solving a wide range of problems involving rotating bodies. This comprehensive guide will walk you through various methods, from basic shapes to more complex scenarios, equipping you with the knowledge to tackle diverse problems effectively.

Understanding the Fundamentals

Before delving into the derivations, let's establish a clear understanding of the fundamental concepts:

What is Moment of Inertia?

Moment of inertia (I), also known as rotational inertia, measures an object's resistance to changes in its rotational speed. It's the rotational equivalent of mass in linear motion. A higher moment of inertia implies a greater resistance to angular acceleration. The formula is fundamentally based on the distribution of mass relative to the axis of rotation. The further the mass is from the axis, the greater the moment of inertia.

The Formula: A Foundation for Derivation

The fundamental formula for moment of inertia is:

I = Σ mᵢrᵢ²

Where:

- I represents the moment of inertia.

- mᵢ is the mass of the i-th particle.

- rᵢ is the perpendicular distance of the i-th particle from the axis of rotation.

- Σ denotes the summation over all particles within the object.

This formula forms the bedrock for all derivations. For continuous objects (not discrete particles), the summation becomes an integral.

Deriving Moment of Inertia for Simple Shapes

Let's explore the derivation for some common shapes:

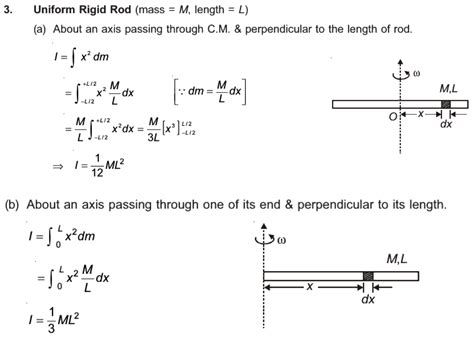

1. Thin Rod Rotating About its End

Consider a thin rod of length 'L' and mass 'M' rotating about one of its ends. We'll use the integral form of the moment of inertia formula.

1. Divide the rod: Imagine the rod divided into infinitesimally small elements of length 'dx' and mass 'dm'.

2. Express dm: The linear mass density (λ) is M/L. Therefore, dm = λdx = (M/L)dx

3. Define r: The distance 'r' of each element from the axis of rotation (the end of the rod) is simply 'x'.

4. Integrate: The moment of inertia becomes:

I = ∫ r² dm = ∫₀ˡ x² (M/L) dx = (M/L) ∫₀ˡ x² dx = (M/L) [x³/3]₀ˡ = (1/3)ML²

Therefore, the moment of inertia of a thin rod rotating about its end is (1/3)ML².

2. Thin Rod Rotating About its Center

For a thin rod rotating about its center, the derivation is similar but with a slight adjustment in the limits of integration.

1. Divide the rod: Again, we divide the rod into infinitesimally small elements of length 'dx' and mass 'dm'.

2. Express dm: dm = (M/L)dx

3. Define r: The distance 'r' of each element from the axis of rotation (the center of the rod) varies from -L/2 to +L/2.

4. Integrate: The moment of inertia becomes:

I = ∫ r² dm = ∫₋ˡ⁄₂⁺ˡ⁄₂ x² (M/L) dx = (M/L) ∫₋ˡ⁄₂⁺ˡ⁄₂ x² dx = (M/L) [x³/3]₋ˡ⁄₂⁺ˡ⁄₂ = (1/12)ML²

Thus, the moment of inertia of a thin rod rotating about its center is (1/12)ML².

3. Solid Cylinder or Disk

Consider a solid cylinder or disk of radius 'R' and mass 'M' rotating about its central axis.

1. Divide the cylinder: We consider thin cylindrical shells of radius 'r', thickness 'dr', and height 'h'.

2. Express dm: The volume of the shell is 2πrh dr. The volume density (ρ) is M/(πR²h). Therefore, dm = ρ(2πrh dr) = (2M/R²)r dr

3. Define r: 'r' is already defined as the radius of the shell.

4. Integrate: The moment of inertia becomes:

I = ∫ r² dm = ∫₀ᴿ r² (2M/R²)r dr = (2M/R²) ∫₀ᴿ r³ dr = (2M/R²) [r⁴/4]₀ᴿ = (1/2)MR²

This gives us the moment of inertia for a solid cylinder or disk rotating about its central axis.

4. Hollow Cylinder or Ring

For a hollow cylinder or ring, the derivation is similar but simpler as we are dealing with a shell of constant radius.

1. Define mass: Let the mass of the ring be M, its radius R.

2. Define r: Every point on the ring is equidistant (R) from the central axis.

3. Direct Application: The moment of inertia is therefore:

I = MR²

This is a straightforward application of the fundamental formula since all the mass is at the same distance from the axis.

5. Solid Sphere

Deriving the moment of inertia for a solid sphere requires a more involved integration process, often using spherical coordinates. This involves integrating over infinitesimal volume elements and involves triple integration. The final result is:

I = (2/5)MR²

6. Hollow Sphere

Similarly, deriving the moment of inertia for a hollow sphere also employs spherical coordinates. The outcome is:

I = (2/3)MR²

Parallel Axis Theorem: Simplifying Complex Derivations

The parallel axis theorem provides a powerful shortcut for calculating the moment of inertia of an object about an axis parallel to its center of mass axis. The theorem states:

I = I<sub>cm</sub> + Md²

Where:

- I is the moment of inertia about the parallel axis.

- I<sub>cm</sub> is the moment of inertia about the center of mass axis.

- M is the total mass of the object.

- d is the perpendicular distance between the two parallel axes.

This theorem significantly simplifies calculations when dealing with objects rotating about axes not passing through their center of mass.

Perpendicular Axis Theorem: A 2D Advantage

The perpendicular axis theorem applies specifically to planar objects (objects with negligible thickness). It states that for a planar lamina, the moment of inertia about an axis perpendicular to the plane is equal to the sum of the moments of inertia about any two mutually perpendicular axes in the plane that intersect at the point where the perpendicular axis passes through the lamina. Mathematically:

I<sub>z</sub> = I<sub>x</sub> + I<sub>y</sub>

Where:

- I<sub>z</sub> is the moment of inertia about the axis perpendicular to the plane.

- I<sub>x</sub> and I<sub>y</sub> are the moments of inertia about the two mutually perpendicular axes in the plane.

This theorem is particularly useful when determining the moment of inertia of irregularly shaped planar objects.

Advanced Techniques and Applications

For more complex shapes or situations involving non-uniform mass distributions, numerical integration techniques or computational methods might be necessary. Software packages employing finite element analysis or similar approaches can handle intricate geometries and mass distributions efficiently. These tools are indispensable for handling real-world scenarios where analytical solutions become intractable.

Conclusion

Deriving the moment of inertia is a fundamental skill in mechanics and engineering. The methods outlined in this guide, ranging from basic integration techniques to the application of the parallel and perpendicular axis theorems, provide a solid foundation for tackling a wide array of problems. Remember that understanding the underlying principles and selecting the appropriate method are key to accurately calculating the moment of inertia for any given object and axis of rotation. The ability to confidently derive moment of inertia is crucial for analyzing rotational motion, designing rotating machinery, and understanding the dynamics of countless physical systems.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

The Longest Phase Of The Cell Cycle Is

Mar 22, 2025

-

Which Of The Following Are Rational Numbers

Mar 22, 2025

-

What Was One Of The Goals Of The Muslim League

Mar 22, 2025

-

How Many Km Is 1 7 Miles

Mar 22, 2025

-

Ode To The West Wind Meaning

Mar 22, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about How To Derive Moment Of Inertia . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.