According To The Fluid Mosaic Model Of Membrane Structure

News Leon

Mar 22, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

According to the Fluid Mosaic Model of Membrane Structure: A Deep Dive

The cell membrane, a ubiquitous structure in all living organisms, isn't merely a static barrier. Instead, it's a dynamic, bustling hub of activity, a complex tapestry of lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates constantly interacting and moving. This dynamic nature is perfectly encapsulated by the fluid mosaic model, a cornerstone of cell biology. This article delves deep into the intricacies of this model, exploring its components, its fluidity, its functions, and the implications of its structure for cellular processes.

The Building Blocks: Lipids, Proteins, and Carbohydrates

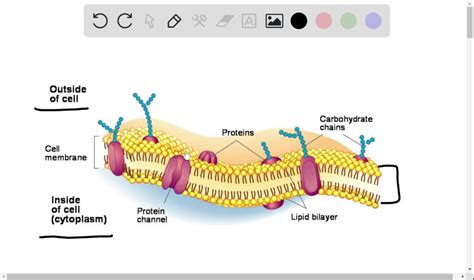

The fluid mosaic model's name itself hints at its essential components: a fluid lipid bilayer studded with a mosaic of proteins. Let's examine each component individually:

1. The Phospholipid Bilayer: The Foundation of Fluidity

The foundation of the cell membrane is the phospholipid bilayer. Phospholipids are amphipathic molecules, meaning they possess both hydrophilic (water-loving) and hydrophobic (water-fearing) regions. Each phospholipid molecule has a hydrophilic head containing a phosphate group and glycerol, and two hydrophobic tails made of fatty acids.

In an aqueous environment, like the inside and outside of a cell, these phospholipids spontaneously arrange themselves into a bilayer. The hydrophilic heads face outwards, interacting with the surrounding water, while the hydrophobic tails cluster together in the interior of the bilayer, avoiding contact with water. This arrangement forms a stable, yet fluid, barrier.

The fluidity of the bilayer is significantly influenced by several factors:

- Fatty acid saturation: Saturated fatty acids, with no double bonds, pack tightly together, making the membrane less fluid. Unsaturated fatty acids, with one or more double bonds, create kinks in their tails, preventing tight packing and increasing fluidity.

- Cholesterol: Cholesterol, a steroid molecule, is embedded within the bilayer. At high temperatures, it restricts phospholipid movement, reducing fluidity. At low temperatures, it prevents the fatty acid tails from packing too tightly, maintaining fluidity.

- Temperature: Higher temperatures increase membrane fluidity, while lower temperatures decrease it. This is why organisms living in extreme temperatures often have adapted membrane compositions to maintain optimal fluidity.

2. Membrane Proteins: The Functional Mosaic

The phospholipid bilayer isn't just a structural scaffold; it's also a platform for a diverse array of membrane proteins. These proteins are responsible for a wide range of cellular functions, and their arrangement within the membrane is crucial for their activity. There are two major classes of membrane proteins:

- Integral proteins: These proteins are embedded within the phospholipid bilayer, often spanning the entire membrane (transmembrane proteins). Their hydrophobic regions interact with the fatty acid tails, while their hydrophilic regions interact with the aqueous environments on either side of the membrane. Integral proteins often serve as channels, transporters, or receptors.

- Peripheral proteins: These proteins are loosely associated with the membrane, often attaching to integral proteins or the phospholipid heads. They play roles in various cellular processes, including signal transduction and cell adhesion.

The diverse functions of membrane proteins include:

- Transport: Moving substances across the membrane (e.g., ion channels, carrier proteins).

- Enzymes: Catalyzing reactions at the membrane surface.

- Receptors: Binding signaling molecules and initiating intracellular responses.

- Cell adhesion: Connecting cells to each other or to the extracellular matrix.

- Cell recognition: Identifying cells as belonging to the same organism or tissue type (often involving glycoproteins).

3. Carbohydrates: The Recognition Layer

Carbohydrates, usually attached to lipids (glycolipids) or proteins (glycoproteins), are found on the outer surface of the cell membrane. These carbohydrate chains form a glycocalyx, a crucial layer involved in cell-cell recognition, cell signaling, and protection. The specific arrangement of carbohydrate molecules on the cell surface acts as a unique identifier, allowing cells to distinguish themselves from other cells. This is essential for processes such as immune response, tissue formation, and fertilization.

The Fluidity: More Than Just a Name

The term "fluid" in the fluid mosaic model isn't just a descriptive adjective; it highlights a critical aspect of membrane function. The phospholipids and proteins within the membrane aren't static; they are constantly moving and interacting. This fluidity allows for:

- Membrane flexibility and deformability: The membrane can bend and fold, allowing cells to change shape and move. This is especially important for cells like white blood cells that need to squeeze through narrow spaces.

- Lateral diffusion: Phospholipids and proteins can move laterally within the plane of the membrane. This movement is essential for processes such as membrane repair and protein trafficking.

- Flip-flop: While less frequent than lateral diffusion, phospholipids can also flip-flop across the bilayer. This process is facilitated by specialized proteins called flippases.

- Membrane trafficking: The fluidity of the membrane allows for the movement of vesicles – small membrane-bound sacs – which transport molecules between different cellular compartments.

The Functions: A Dynamic Barrier and More

The fluid mosaic model's structure is intimately linked to its diverse functions:

- Selective permeability: The membrane acts as a selectively permeable barrier, regulating the passage of substances into and out of the cell. Small, nonpolar molecules can diffuse across the membrane freely, while larger or polar molecules require the assistance of membrane proteins.

- Cell signaling: The membrane is the primary site for cell signaling, where receptors bind to signaling molecules and trigger intracellular responses. This communication is essential for coordinating cellular activities and responding to environmental changes.

- Cell-cell recognition and adhesion: The carbohydrate layer and specific membrane proteins mediate cell-cell interactions, allowing cells to recognize each other and adhere to form tissues and organs.

- Energy transduction: In some cells, the membrane is the site of energy production, such as in the mitochondrial inner membrane where the electron transport chain operates.

- Maintaining homeostasis: The membrane regulates the internal environment of the cell, maintaining a stable composition of ions and molecules despite fluctuations in the external environment.

Variations and Adaptations of the Model

While the fluid mosaic model provides a general framework for understanding cell membrane structure, it's important to recognize that there are variations and adaptations depending on the cell type and its environment. For instance:

- Membrane composition: The relative proportions of lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates vary greatly between different cell types and even between different regions of the same membrane.

- Specialized membrane domains: Some membranes contain specialized domains with unique compositions and functions, such as lipid rafts, which are enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids.

- Membrane asymmetry: The two leaflets of the bilayer are often asymmetric, with different lipid and protein compositions on the inner and outer surfaces.

Experimental Evidence Supporting the Model

The fluid mosaic model isn't just a theoretical construct; it's supported by a wealth of experimental evidence, including:

- Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP): This technique demonstrates the lateral diffusion of membrane proteins by labeling them with fluorescent dyes and then bleaching a small area with a laser. The recovery of fluorescence in the bleached area shows that proteins are moving laterally.

- Electron microscopy: This technique provides high-resolution images of the membrane, revealing the bilayer structure and the presence of embedded proteins.

- Freeze-fracture electron microscopy: This technique allows visualization of the interior of the membrane, revealing the distribution of membrane proteins.

Conclusion: A Dynamic System for Life

The fluid mosaic model stands as a testament to the remarkable complexity and dynamism of biological systems. The cell membrane, far from being a simple barrier, is a sophisticated, self-regulating structure that orchestrates a myriad of essential cellular processes. Its fluidity is not a mere incidental property but a fundamental feature that enables its diverse functions. Understanding the intricacies of this model is paramount to comprehending the workings of cells and the functioning of life itself. The ongoing research continues to refine our understanding of the membrane's intricacies, revealing ever-more nuanced details about its remarkable structure and functions, solidifying its position as a central concept in cell biology. Further investigation into the specific interactions between different membrane components and the detailed mechanisms of membrane trafficking will undoubtedly uncover even more exciting discoveries about this fundamental structure of life.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Which Expression Is Equivalent To 9 2

Mar 22, 2025

-

In The Figure Three Connected Blocks Are Pulled

Mar 22, 2025

-

Draw The Structure Of A Nucleotide And Label The Parts

Mar 22, 2025

-

An Unknown Resistor Is Connected Between The Terminals Of A

Mar 22, 2025

-

Iron Containing Pigment Is Referred To As

Mar 22, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about According To The Fluid Mosaic Model Of Membrane Structure . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.